'A TEMPEST IN A TEAPOT’ – DUNRAVEN’S 1895 CHALLENGE

The British, it could be said, had caught America’s Cup fever with a strong sense that the impossible might just be achieved with the right preparation and a challenge of the highest specification. From the outset, Lord Dunraven’s second official challenge sought to operate on a level unseen before but underestimated the might and will of the New York Yacht Club to defend. The 1895 challenge was to end, as The Lawson History records ‘with a cloud on the sport’ that added once more to the prestige, myth and magic of the America’s Cup.

In correspondence in 1894 ahead of the official documentation being accepted, Lord Dunraven and the Royal Yacht Squadron secured a vital concession from the New York Yacht Club that a challenger could substitute its entered vessel for a faster yacht if it so wished. On other terms desired, it wasn’t so successful, and the Americans played hardball around terms of the Deed of Gift and argued successfully that the one-gun starts that had been employed in the 1893 races should not be used again. Lord Dunraven accepted the terms, and a formal challenge was issued on December 6th, 1894, stating that a yacht called ‘Valkyrie’ of 89 feet would contest a five-race match for the America’s Cup, whilst a previous correspondence cabled on the 1st December but not received until the 10th December asked for a period of eight months to commencement.

Further back and forth ensued however between the two clubs, with the Royal Yacht Squadron at first refusing to accept the Cup, should they be victorious under the obligations to the conditions of the New York Yacht Club stating in a curt cable: “If challenge accepted now and representative wins, Squadron will not demand Cup, failing satisfactory agreement as to receipt.” The New York Yacht Club replied on December 17th, 1894, stating that it did not “agree that the Squadron had the right, after having won the cup, to reject custody of it” according to the terms of the Deed of Gift and that it would wait until January 15th, 1895, for a reply on the matter. In a crucial communique on the 7th of January 1895, the Royal Yacht Squadron went on record as accepting the: “construction placed on the Deed of Gift…and willing to give receipt on terms contained in the Deed of Gift 1887.” From there, negotiations ran smoothly, and the Match date was set for September 7th, 1895.

In meeting the British challenge, the Americans formed a powerful syndicate of William K. Vanderbilt, E.D. Morgan and C. Oliver Iselin who threw a shroud of secrecy over the build of the first keeled boat to defend the Cup – a sloop called Defender. “Expense was not regarded in building her,” records The Lawson History, “and in the use of so light and strong a metal as aluminium in her construction, Herreshoff realised a dream of yacht designers.”

This was a radical build all round from hull to deck to even the vessel’s fittings that a respected Naval constructor (Richmond Pearson Hobson) estimated: “about seventeen tons dead weight was saved” in creating “the extreme racing machine of her day.” Indeed, it could be argued that she was the first Cup boat built solely for the purpose of defending the America’s Cup and her after-life was short having suffered from rapid corrosion through galvanic action induced by the combination of materials employed in her hull. Defender was broken up in 1901, just six years later.

For the Cup races of 1895, Defender employed a wholly American crew for the first time, doing away with the usual staple of Swedish and Norwegian hands in favour of ‘Yankee sailors shipped at Deer Isle, Maine.’ Captain ‘Hank’ Haff was again appointed as commander, but the early trials were anything but smooth sailing. Defender was fast, but a tricky series of opening races ahead of the trials against a re-vamped Vigilant, in the ownership of George J. Gould, very nearly saw her ineligible to race for the New York Yacht Club under its racing rules at the time.

The Vigilant, under the management of Mr E. A. Willard and commanded by Captain Charles Barr met Defender on July 22nd, 1895, off Sandy Hook and an ensuing start-box protest for bearing-down looked highly likely to be upheld by the committee. Mr Willard asked that the result be held until the two boats reached Newport after the club’s cruise and the two boats didn’t meet again until August 6th, 1895.

Again, there was controversy in the pre-start with Vigilant feeling that Defender had borne down on them unfairly in the lead into the line, but The Lawson History records that: “another complaint was made by Mr Willard, who was a clear-headed and able Corinthian yachtsman of good standing, against the manner in which Mr Iselin’s boat was handled in the start. Mr Willard refrained from protesting, for the reason that a boat twice found in the wrong under protest could not again sail in the races under the club’s auspices.”

Vigilant was subsequently withdrawn from all further racing and created a media storm, described as ‘a tempest in a teapot’ with each party defending themselves through the newspapers and journals of the time. Captain Barr even stated in one: “I have declined positively to sail again unless things are changed. I have been made a fool of. Vigilant has had the better positions, and it is unfair that we should have to give way all the time.” Ahead of the official trials, peace broke out and cups were offered for the racing by Colonel John Jacob Astor. Defender won the trial series 2-1 having lost a race due to mast damage whilst ahead in race one that was swiftly replaced at Bristol, Rhode Island and she was at once formally selected to defend the Cup after the next two decisive wins. In that summer’s tune up regattas, Defender was coming to peak performance. It was different story for the Challenger.

Lord Dunraven’s syndicate comprised of fellow-owners: Lord Lonsdale, Lord Wolverton and Captain Harry McCalmont who brought the George L. Watson designed Valkyrie III to America as the beamiest challenger ever, in fact the beamiest boat in Cup history at the time. She was built at the D&W Henderson & Co. yard on the Clyde of composite construction with steel frames planked with wood, American elm below the water-line and teak above. After initial trials where she was off the pace, Valkyrie III had some twelve tons of lead added to her ballast and was crewed by Wivenhoe men from the east coast fisheries. That summer of 1895 she trialled against Britannia and Ailsa and with the addition to the ballast proved herself as: “unquestionably England’s speediest boat,” according to The Lawson.

On arrival in New York on August 18th, 1895, Valkyrie III had little time to adapt from ocean going vessel to Cup racer. Racing spars were brought by steamer – one of Oregon pine, the other of steel that ‘American yacht sailors were doubtful if a steel mainmast for a racer could ever be made to stand up.’ Furthermore, a boom made from galvanised steel to a hexagonal shape that measured one hundred and five feet with a girth of twenty-two inches at its widest was delivered and used – the steel mast however was not. Interest built in the yachting circles with The Lawson recording that: “Challenger and Defender were nearer alike, and more evenly matched, than any vessels that had been raced for the Cup.”

However, this regatta was to descend into acrimony, expulsion, exclusion, slanging and controversy more so than perhaps any before or since in the history of the America’s Cup. Described by a journal in New England as a ‘miserable fiasco’ the 1895 Cup races bordered on the farcical that produced such ill-will amidst accusations of fraud, misrepresentation, extraordinary conduct and mis-trust that it is recorded that: “when he (Lord Dunraven) returned to England, he was easily the most unpopular Englishman whoever left this country,” according to The Lawson.

The series itself was unremarkable on the water with the first race being a light-weather affair started on the 7th September 1895 in a forenoon breeze that varied between 6-8 knots but amidst a heavy swell, the remnants of an offshore storm, that ill-suited the beamier Valkyrie III. The spectator fleet of steamers and cruisers were patrolled by some twenty official vessels of the New York Yacht Club all carrying the club’s distinctive flag creating a ‘tolerably clear’ path for the boats to compete. Spectator craft had always been an issue and a topic that Lord Dunraven had brought up a number of times with even a suggestion made that the racing should be held off the relatively wider expanses of Marblehead than in close proximity to the City which would naturally attract more interest. The NYYC Committee however felt that by instigating marshal boats, the situation would abate. It ended up being a crucial factor in the acrimony.

When the first starting gun sounded that afternoon, it was Valkyrie III that crossed first, setting the finest sails seen on a challenging yacht in history and hauling to weather faster than Defender but as the race settled, it was the American boat that managed to cross first, a feat that the British had tried and failed at minutes earlier, and the tale of the tape shows that once ahead, the rich got richer. Defender won by 8 minutes 49 seconds on corrected time, and it felt safe to assume that that was the end of the matter. However, when the yachts came to port that night, the regatta and Cup committees had been informed that Lord Dunraven had: “made a charge bearing an imputation of fraud, to Mr Latham A. Fish, the NYYC member sailing onboard Defender, namely: That in his opinion Defender sailed the race immersed three or four feet beyond her length as measured on September 6th.” This was coupled with a request for re-measurement.

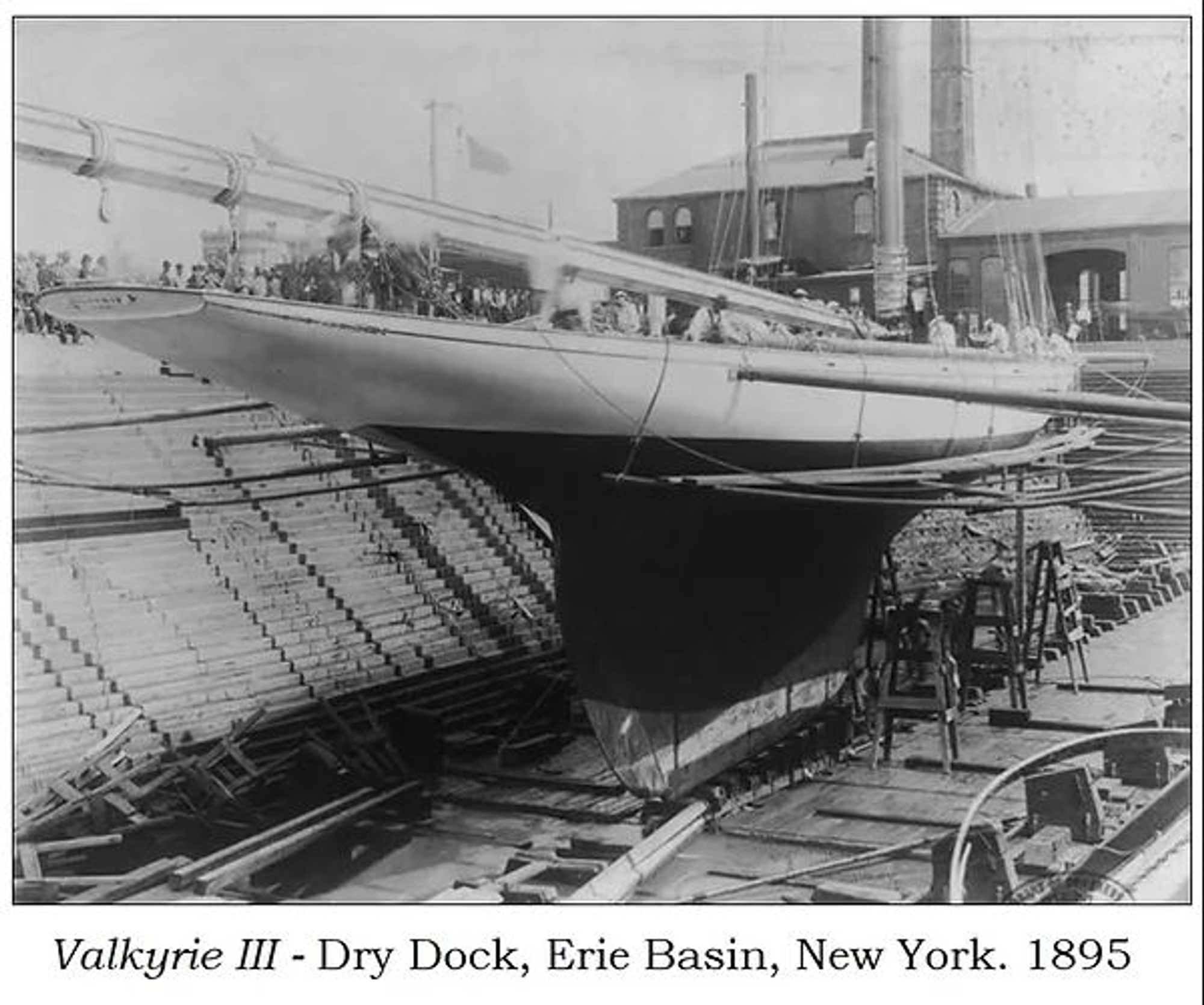

Subsequently the America’s Cup Committee reported that Lord Dunraven: “believed the change had been made without the knowledge of Defender’s owners but that it must be corrected or he would discontinue racing.” Both boats were towed up to Eerie Basin on the 8th September 1895, re-measured, and marked with only one-eighth of an inch difference found in the waterline measurement of Defender. But the accusation of fraud and the recrimination afterwards was something that would see Lord Dunraven expelled from his honorary membership of the NYYC and haunted the memory of this cycle of the Cup for years to come.

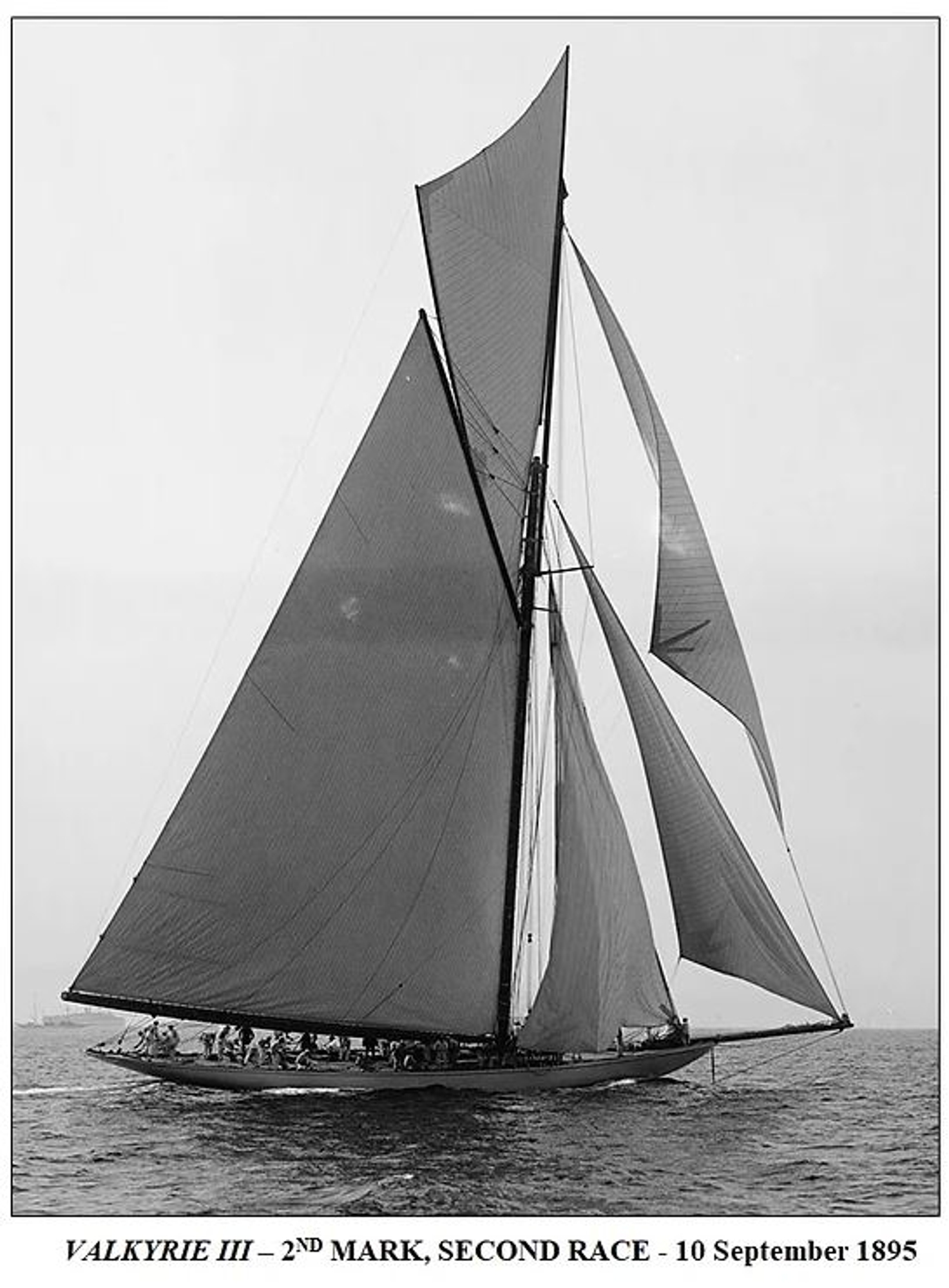

With the public unknowing of the shadow that was being cast over the sport and what was really happening behind the scenes, the second race of the series attracted wide public interest on September 10th, 1895, and was started again in desperately light conditions with the wind no more than 5 miles an hour. The Lawson records the pre-start as: “About two minutes before gun-fire the racers, which had stood to the westward of the line, jibed to the starboard tack, and headed for the line in a south-easterly direction. In their course and about six hundred yards from the line, lay the large steamer City of Yorktown, carrying excursionists. Defender went astern and to leeward of her, and Valkyrie by her bow. As the two boats cleared the Yorktown their courses converged for the line in an acute angle, Valkyrie to windward and nearer the line, though Defender was sailing the faster. It was apparent to all who saw the courses of the vessels that unless one or the other gave way they would foul before the line was reached.”

Defender held her course to the line whilst Valkyrie III bore down to make the line and as the two came together, Captain Sycamore on the British boat wheeled up an instant too soon, luffing into the wind and in the process, the shackle of the iron strap on the end of Valkyrie’s main-boom caught in Defender’s starboard topmast-shroud. Shouts of “outrageous” and “shameful” were heard from the American yacht whilst a scarlet protest flag, a source of some contention later, fluttered on her deck. The all-American crew struggled to lash the wildly bending topmast and reduced sail, crossing the start-line over a minute adrift and handed a near three-minute lead to the British by the first turning mark to windward. But Defender was fast, even when handicapped by reduced sail and over the course of a classic America’s Cup match-race, closed the gap relentlessly as the wind freshened to 10 knots to finish just 1 minute and 16 seconds behind on elapsed time and a mere 47 seconds on corrected time.

Once ashore, C. Oliver Iselin, the master of Defender, lodged a protest with “much regret” as his statement to the NYYC opened and in the committee hearing, photographic evidence was also considered. The judgement was swift: “We find that Valkyrie, in contravention of Section II of racing rule 16, bore down upon Defender, and fouled her by the swing of her main-boom when luffing to straighten her course.” The race was summarily awarded to Defender, despite Mr Iselin offering, rather generously, to re-race. An offer that was declined by Lord Dunraven who bitterly disputed the findings of the committee both at the time and in later correspondence but also that evening sent a further communication to the committee regarding the presence of spectators on the course.

Whilst complaining bitterly about the confines of the starting area, Lord Dunraven highlighted safety of his vessel and crew amidst the mass of spectators and followed up further with: “To-day, on the reach home, eight or nine steamers crossed my bow, several were to windward of me, and, what was worse, a block of steamers were steaming level with me, and close under my lee. I sailed nearly the whole distance in tumbling, broken water, in the heavy wash of these steamers. To race under these conditions is absurd, and I decline to submit myself to them again.”

Representatives of the NYYC Cup Committee were hurriedly sent to Lord Dunraven to try and broker a peace on September 11th, 1895, but to no avail with the British yachtsman addressing a letter back that evening stating that: “he wished for the ensuing race to be declared void if the vessels were interfered with by steamers.” Under the regatta terms, the committee had no authority to declare this, so the race was scheduled for September 12th and the regatta committee instructed to proceed as normal.

With a huge presence on the water for what could be the deciding match of the America’s Cup in 1895, Valkyrie III came out to the race-course area under jib and mainsail alone with no topsail aloft – clearly a marker that she was not preparing to race. With the starting area clearer than had ever been seen for a race off Sandy Hook due to judicious marshalling, and against a backdrop reported in the newspapers that morning that Lord Dunraven was about “to quit” the spectators were agitated to see what would unfold. After a 15-minute delay, the preparatory signal was sounded at 11.00am with none of the usual jockeying for position and Valkyrie a fair distance from the line. At 11.20am the starting gun fired and only Defender came to the line, crossing 24 seconds after the signal, meanwhile Valkyrie crossed at 11.21.59 and immediately jammed her tiller down, coming up under the stern of the light-vessel and headed for port whilst breaking out the New York Yacht Club flag at the truck.

It was a bizarre conclusion to the most extraordinary America’s Cup match. Defender completed the course and retained the silver ewer for the New York Yacht Club, but the repercussions lasted through the rest of 1895 with Lord Dunraven being published in the London Field magazine, again re-iterating his claim that Defender had sailed in a trim at least “four inches deeper” than measured in that first race.

The New York Yacht Club were incensed at the accusation and undertones of “fraud” that they simply could not ignore and in particular Mr Iselin, the managing owner of Defender, felt aggrieved. On November 18th 1895, he wrote to the NYYC stating: “with an offence as base as possibly could be imputed to a sportsman and a gentleman, and which I indignantly resent and repel, and more than that: with having betrayed the confidence of my associates in the ownership of the Defender, the trust placed in me by the NYYC, and the good name of my country, whose reputation for fair play was involved in the contest.”

A high-ranking inquiry committee was set up by the NYYC with heavyweight appointees from ambassadorial, political and maritime authorities and testimony was called by all involved including Mr Latham A. Fish alongside civil engineers, respected boatbuilders, yachtsmen from Defender including Captain ‘Hank’ Haff, serving naval officers, and of course, Lord Dunraven himself who had been doubling down on his accusations with increasing vitriol and passion both in public and via the press.

The result of all this, was that on February 27th, 1896, the New York Yacht Club announced in a curt statement the results of the extensive commission findings. Lord Dunraven was hung out to dry with lines such as: “It is not open to discussion that when gentlemen are engaged in any sport and one suspects another of foul play, he is bound to make the charge good, and in such form and manner as to assume full responsibility therefore, or thereafter to remain silent.”

The last word on the matter was final in its execution: “Lord Dunraven, by this course, has forfeited the high esteem which led to his election as an honorary member of this club, therefore the privileges of honorary membership heretofore extended to the Earl of Dunraven are hereby withdrawn and that his name be withdrawn from the list of honorary members of the club.”

Windham Wyndham-Quin, the 4th Earl of Dunraven and Mount-Earl was never again seen in the America’s Cup.

UP NEXT: 1899 – THE LIPTON ERA BEGINS