THE LIPTON ERA BEGINS

After the acrimony and bitterness that ensued after Lord Dunraven’s challenge of 1895, it was feared that the English would place a permanent cessation on contests for the America’s Cup but that was before one of the most intriguing businessmen of the time entered the fray.

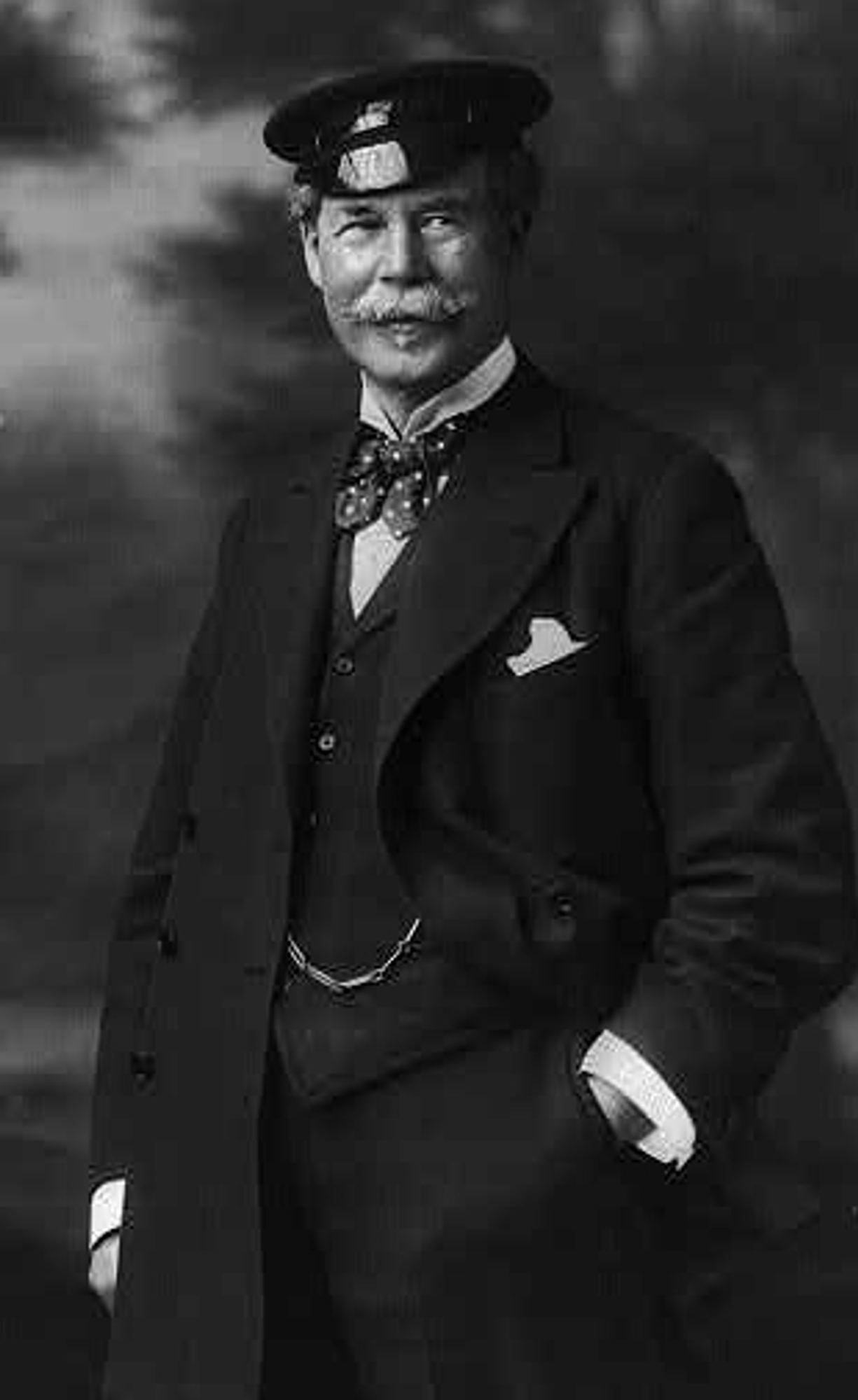

The Cup has always attracted larger-than-life characters and in Sir Thomas J. Lipton none was more colourful. The Lawson History offers lavish praise of this popular challenge from the Royal Ulster Yacht Club: “Throughout the yachting season his fleet of yachts, tugs and tenders carried his striking private signal, a vivid green Shamrock on a yellow ground, with a broad green border, into all parts of New York Bay. The newspapers printed many columns describing his wonderful rise in the world since the days of his early experiences as a dock labourer in New York; of his vast tea plantations, his pork-packing interests in the West, his great grocery store syndicate in England with its capital of millions of pounds sterling, of his dinner parties, his rare wines, his Cingalese servants, his grace as a host and his chivalric devotion to American women, with a jocular allusion to the possibility of his losing his bachelor heart to some fair one among the American girls he met.”

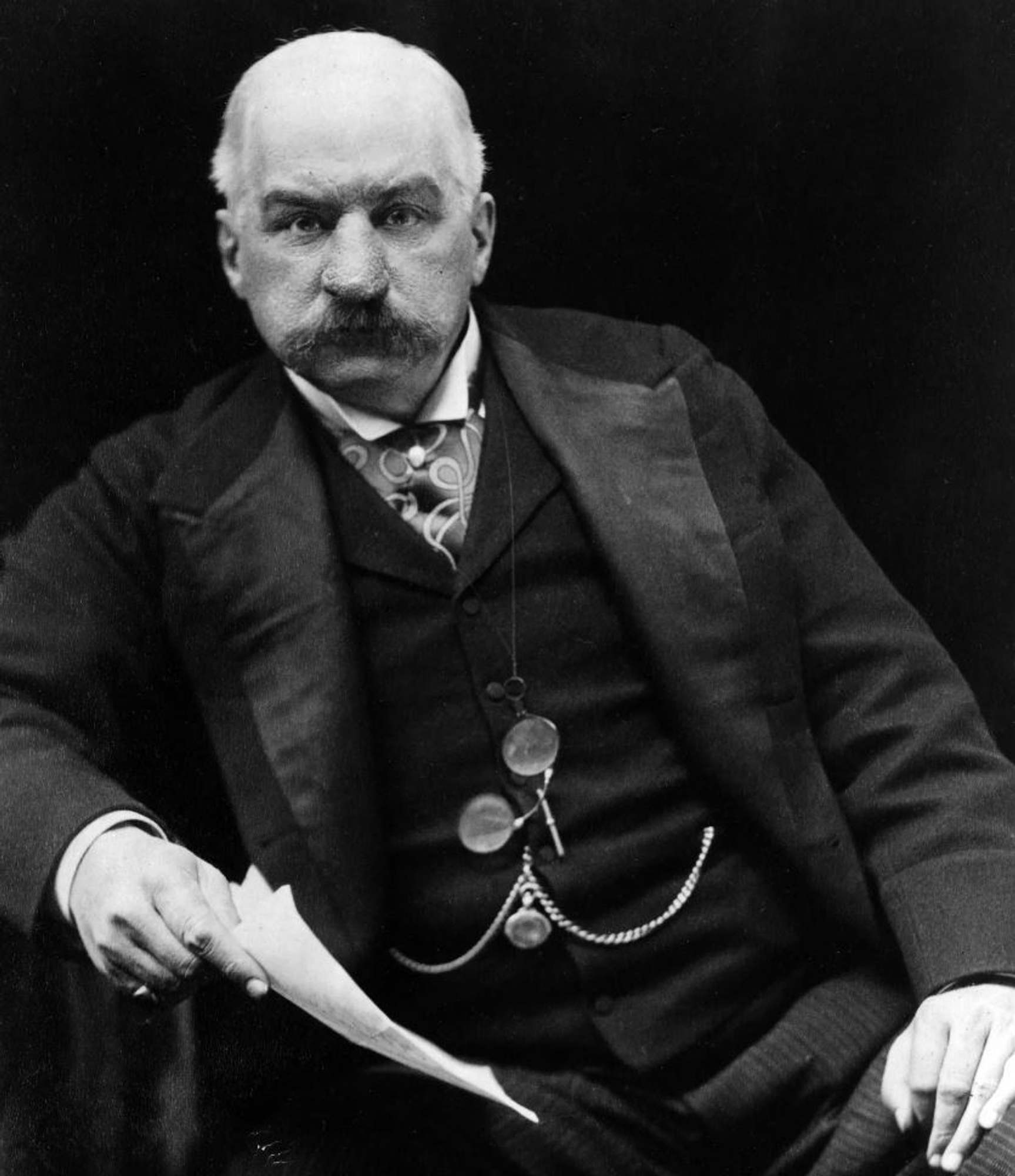

The challenge was issued on August 6th, 1898, and relations between the New York Yacht Club committee and the challenging committee of the Royal Ulster Yacht Club were seen as being more than cordial. But this was to be a money-no-object Cup with the bottomless pockets of Lipton met full-square by the banking might of J.Pierpont Morgan. Estimates show that both defender and challenger spent somewhere in the region of $250,000 each on their vessels, although official records were never published, an eye-watering sum of money at the time that produced two of the finest vessels ever to race for the America’s Cup in the Shamrock and the Columbia.

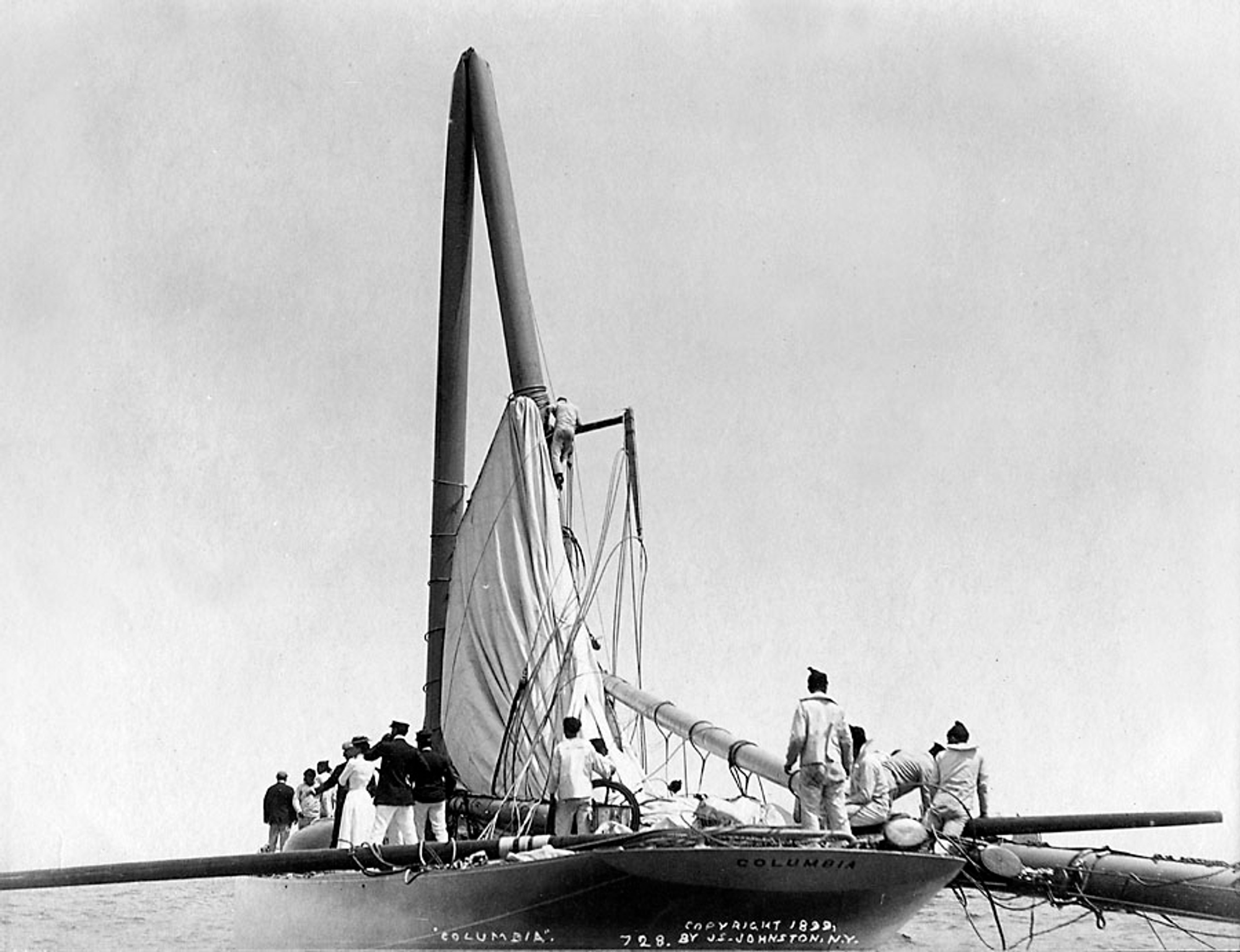

After convivial negotiations, described as ‘superlatively friendly intercourse’ the contest was agreed for dates in October 1899 with Sir Thomas Lipton asking for little and conceding much – viewed in the eyes of the NYYC as ‘an ideal challenger.’ With ever more exotic materials, such as bronze, creeping into the build of modern-day racers, only the very rich could afford to enter now and as the defender was laid down early in the winter of 1898-1899 at the Herreshoff yard in Bristol, great secrecy was demanded. In time, it was revealed that Columbia was plated in Tobin bronze with nickel-steel frames and was a step-on in design from Defender that bested Lord Dunraven’s Valkyrie III in 1895 with more beam and draft, a shallower body and finer overhangs. In total she measured in at 131 feet with a beam of 24.17 feet and a draft of 19.75 feet.

Shamrock meanwhile was being built at Thorneycroft’s yard in Millwall on the Thames, near London and again, no expense was spared. Manganese bronze was applied to her underbody whilst her topsides were of alloyed aluminium. At launch on June 24th, 1899, it was believed that Shamrock was the fastest challenger ever to leave England and in early trials her performance seemed to prove her speed – in reality, American boatbuilding and preparation had significantly over-taken the British and in comparison, Shamrock would have been an excellent vessel to challenge Defender of the 1895 Cup but Columbia was a significant advance, as was proven. In light airs however, Shamrock was described as “a witch” and many of the yachting fraternity in and around New York that summer felt that Columbia had a lot to do to beat the challenger.

In early trial races that summer, Columbia proved herself against Defender despite one race on August 2nd, 1899, where her steel mast came tumbling to the deck – the first recorded breakage of a steel mast in Cup racing. It was quickly replaced, and Columbia went on to record consistent victories over Defender and was duly selected as the yacht to defend the America’s Cup on September 4th, 1899, at a meeting held aboard the NYYC flagship ‘Corsair’ with the official decision relayed to Sir Thomas Lipton on September 25th 1899.

Of note was a remarkable act of congress that was passed in May 1896 at the insistence of prominent members of the NYYC that ensured the problems of over-crowding on the racecourse be banished to the record books. This act was an amendment to section 4487 of the revised statutes and navigation laws of the United States and provided for one mile of clear water for the yachts to sail in at all times and half a mile on all sides at the starts. Patrolling the Cup matches were six revenue cutters and six torpedo boats, whilst detailed charts indicating the courses to be sailed were issued to all steamer captains of the New York fleet. The stamp of government authority had the desired effect and crowding, so controversial in previous America’s Cup Matches, thus became a thing of the past.

With everything set for a momentous series, it is recorded in The Lawson that: “No series of races in the cup’s history was ever sailed under such adverse and trying conditions as that between Columbia and Shamrock. An unprecedented period of foggy weather and light airs made it impossible to secure a race until thirteen days from the first day set of October 3rd 1899.” Despite the conditions, on October 3rd, 1899, the largest excursion fleet even seen in New York ventured out on to the racecourse but as the wind barely registered above 5 knots, the race was cancelled in the late afternoon dying light at 4.45pm. And it was the same story for the next seven attempts to get a race away as persistent fog and light airs dogged the regatta so it wasn’t until Monday October 16th, 1899, that the spectators patience was finally rewarded with a completed race.

However, race one was a dull affair that started in 10 knots of fair breeze but by the mid-way point had dropped to a zephyr. Columbia came to the start-line just behind but to weather and her superior pointing ability rose to the fore and within just half an hour she was an eighth of a mile ahead. By the first turn at the windward mark, the Columbia's lead was a mile and a quarter and by the end of the race, after a small time allowance of six seconds was applied in favour of Shamrock, Columbia won by the considerable margin of 10 minutes 8 seconds.

The two yachts faced off again the very next day with a decent breeze and a fine prospect in store for the vast spectator fleet. Columbia won the start, but Shamrock set up in a weather position, blanketing the American yacht. It was short-lived though as Columbia footed away and powered through Shamrock’s lee with unmatched speed much to the whoops and cheers of the watchers. As the boats came back on the port tack, 25 minutes into the race, Columbia held a significant advantage before disaster befell Shamrock as her topmast carrying her largest club-topsail broke off at the cap and descended to the deck. Immediately the crew hauled into the wind to clear the wreckage, but their race was over and Columbia went on to complete the course – a stipulation that had been agreed on before the regatta had started – to claim a 2-0 lead with The Lawson recording that: “No-one wanted such an empty victory, but under the terms of agreement covering the point there was nothing to do but accept the race.”

The deficiencies in Shamrock were being exposed brutally by the Americans and the topmast failure was simply another example of the boat’s problems. Many watchers viewed the Shamrock as being too lightly sparred for the contest and whilst another topmast was rigged and set that evening, Sir Thomas Lipton insisted that more lead be placed in the keel, convinced as he was that this would improve performance. Shamrock was re-measured at Eerie Basin and her waterline length rose from 87.69 feet to 88.98 feet – a considerable difference – and altered the time allowance from six seconds to the good, to 16 seconds to Columbia.

After a delay due to adverse conditions, the next and last time the yachts met was on October 20th, 1899, in a humdinger of a race in big conditions that called for the crews to be fully decked in oilskins as the white horses off Sandy Hook thundered down the hulls. Shamrock revelled in the conditions and at the start-line both boats “came for the line on the starboard tack, bowling along with rails under and foam billowing from their bows.” Shamrock crossed just 35 seconds after the puff of smoke had cleared from the gun with Columbia a full minute and one second later. With this being a running start, both boats set vast spinnakers with Columbia giving chase and aiming directly for Shamrock’s stern to blanket her, but the Americans were noticeably struggling with the spinnaker pole that was lofting skywards, spilling the wind and collapsing the spinnaker.

Described as “the finest fifteen-mile run in international yachting history,” Columbia drew level with Shamrock after an hour of sailing having sailed lower than the Irish yacht and eventually breaking through her lee to secure the lead and as The Lawson records: “In the moving pictures of these scenes the yachts were a delight to the eye. Their bulging canvas, hard and taut; the foam rolling so gracefully from their bows; the water hissing along their smooth metal hulls; the crested waves all around them – all these component parts made a whole not soon forgotten.”

At the turning mark, the Americans held a seventeen second lead and Shamrock did everything to gain a weather gauge, luffing into the wind before re-setting. Columbia responded but as the two yachts settled into a long port tack, the superior pointing of the Americans once again proved unstoppable and with the spray flying at times, half-way up the mainmast of Shamrock, it was clear that the added lead was having a detrimental affect on performance. The crew of Shamrock threw up every available sail in a last-ditch attempt to close the gap, but Columbia was mighty and quickly established a quarter of a mile lead that she would never relinquish.

By the finish line amidst dramatic autumnal skies that shone brief light onto the gleaming hull of Columbia, the Americans were half a mile ahead recording a win of over six and a half minutes and securing the America’s Cup for the New York Yacht Club. It was a stunning victory by the finest yacht of its day and although soundly beaten, that evening Sir Thomas Lipton announced his intention to challenge again. In the newspapers and journals of the time, Lipton found good favour with it recorded that: “Lipton was voted the most democratic man who ever challenged for the Cup, and a good loser. He was everybody’s friend, hail-fellow-well-met, and at club banquets and other social gatherings which he attended before returning to England he spoke eloquently of his admiration for Americans, and for America, where he laid the foundations for his success in life.”

Shamrock was towed back to England, via the Azores, arriving on the 17th November 1899 with Lipton determined to “lift the Cup” and go again. He was greeted by his friend, the Prince of Wales, on his arrival back in Britain and set about challenging again through the Royal Ulster Yacht Club in October 1900.

The Lipton era had begun.

CONTINUE READING ABOUT THE 1901 CUP: LIPTON CHALLENGES AGAIN