LIPTON CHALLENGES AGAIN

When the Royal Ulster Yacht Club issued its challenge to the New York Yacht Club on behalf of Sir Thomas Lipton on October 2nd, 1900, it could not have been foreseen the turmoil that would ensue in American yachting circles. No real advance had been identified in terms of design such was the money-no-object spirit of the times in sailing for the America’s Cup that had pervaded with the arrival of J.Pierpont Morgan with Columbia and Lipton with Shamrock I.

Indeed, it could be argued that the 1901 racing was a step back to the future although what proceeded the Americans and Irish lining up for the Match that year was to send shockwaves through the sport on the East coast and define the coming era of the America’s Cup for heightened professionalism and dedication.

Two new boats were built with the specific purpose of defending the Cup for the New York Yacht Club – the Constitution and the Independence – but neither was selected, and it was in acrimonious circumstances that the trials of 1901 concluded. The Constitution, built and fitted out entirely at the Herreshoff yard, and owned by a syndicate of prominent New York Yacht Club members was the great hope whilst the Independence, built for Thomas W. Lawson was supposed to bring pride back to the shipyards of Boston and Massachusetts Bay. The fact that both yachts were out-sailed and out-classed by the 1899 defender, Columbia, spoke more to their mismanagement than their inherent performance characteristics. And the competition between the highly proficient and professional Charles Barr, steering Columbia and the inconsistent Uria Rhodes on Constitution intensified through the summer whilst Captain Hank Haff, commanding Independence had a torrid time. Without wishing to take a chance on the destiny of the Cup, the New York Yacht Club committee selected the 1899 defender Columbia, but the ramifications were long.

It is worth dwelling on the outcome of the defence trials before coming to the Cup races themselves and the most authoritative yachting journal of the time, The Rudder, chronicled the difference between Columbia and Constitution with much eloquence, writing in 1901: “To show the difference between the manner in which the two boats were run, it is only necessary to paint two pictures. It was the day of the last trial race, say ten minutes before they doused spinnakers to make the finish. On the Columbia, Barr stood behind the wheel; about him for a space of ten feet the deck was absolutely clear, except just in front sat one man who never moved, and his kept his eyes in front. Then torn to the Constitution; the space about Rhodes looked like the corner of a country main street on a Saturday night. Herreshoff, in his shirt sleeves, stood behind the skipper; to his right was a group of three gentlemen talking, pointing and gesticulating. Two or three other men walked about the decks and in the companion sat two ladies. On one deck, business, silence and order such as should be on a racing yacht; on the other an excursion party.”

“On the Columbia the crew were, for all the movement they made, part of their vessel. When called upon to execute an order they rose, acted and returned to their positions like well-trained parts of a machine. On the Constitution the crew, under the distracting example of people moving about the decks, lolled about uneasily; when they rose to carry out an order they did so in a straggling and ragged manner.”

More importantly, and of historical note were the sage words written in The Rudder by Thomas Fleming Ray, the editor when unbeknown to him, he ushered in the era of high professionalism in the America’s Cup saying: “Yacht racing is a business. To be successful you must cast aside all ulterior considerations, and work only to win. You must have the best sails, no matter who makes them; you must have your decks clear of idlers, no matter whose friends they are; you must have the cleverest skipper and best trained crew, despite the fact that the builder of the boat wants somebody else. You must know no fear and show no favour. The will that moulds men and means to an end regardless of personal ties or business associations is the will needed in such a task. System, discipline, order, the submission of all to purpose. This never can exist under a single and uncontrolled head.”

So, with the American yachting scene set, and with wild accusations flowing about the demise of Herreshoff amid suggestions of sharp business practices around the cloth used for the sails of Constitution, the 1901 America’s Cup was very much a watershed moment for the New York Yacht Club. The public’s interest was waning and their outlook for a successful defence in 1901 was darkening. It was further captured by Thomas Fleming Day in The Rudder in an excoriating article that proclaimed: “For the sake of the sport I would like to see Sir Thomas Lipton win. As it is, the contest is too one-sided, but if the Cup could be passed and re-passed across the ocean it would be better for yachting on both sides.”

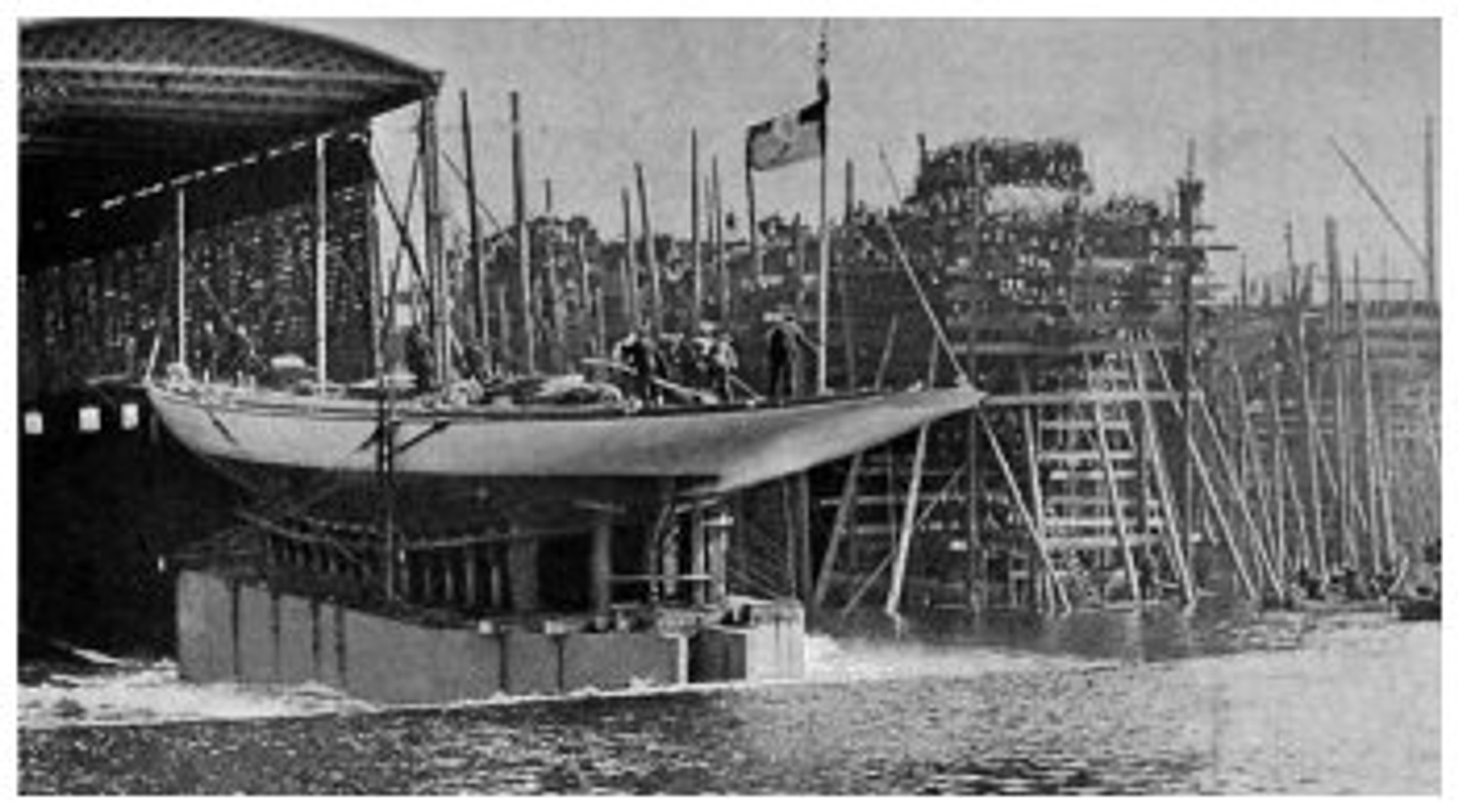

Whilst travails and worry continued in America, they perhaps lost sight of the problems that Sir Thomas Lipton was having on the other side of the Atlantic. Having commissioned Shamrock II from the design-board of G.L Watson, after discarding the services of Fife, Lipton gave the designer a: “free hand and the cleverest builders in Britain were employed to construct the vessel where five-pound notes were to be ‘shovelled-on’ to spur all concerned.” Shamrock II was launched from the yard of Messrs. William Denny & Brother at Dumbarton on the River Leven on April 20th 1901 and towed down to Cowes to primarily trial against the defeated Shamrock I of 1899. Early racing was almost too tight to call with each boat taking races as Shamrock II struggled with rig tune and sail set.

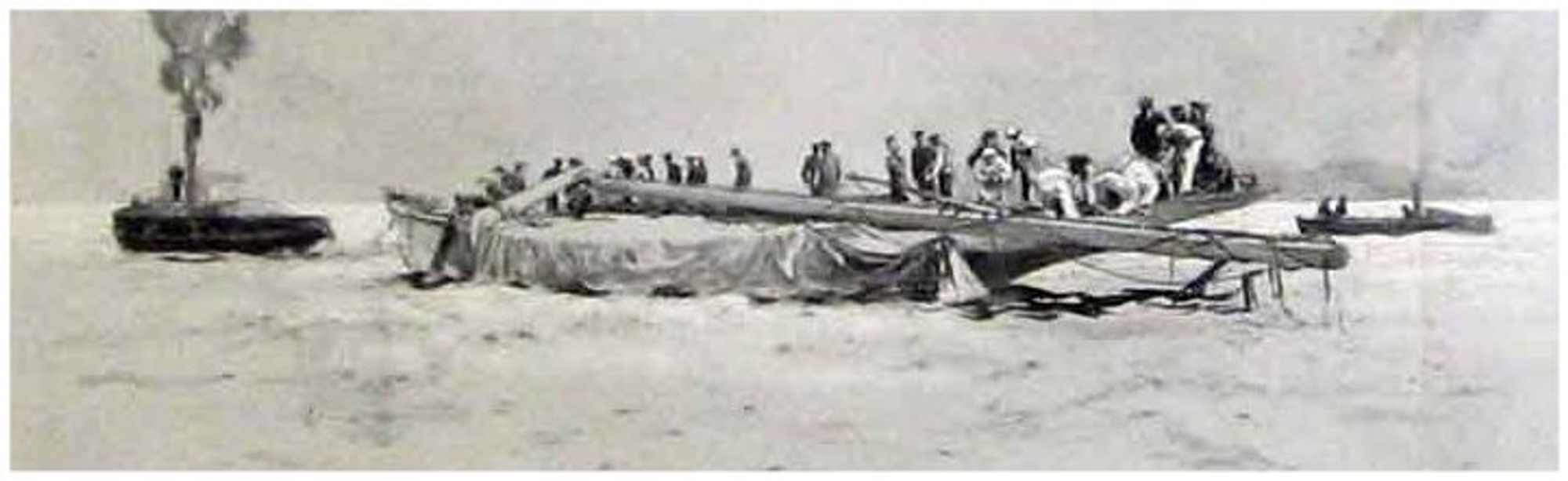

A notable incident occurred during the third trial on May 22nd, 1901, whilst King Edward VII was onboard having requested to sail and travelling down to Southampton to be transferred by the steam-yacht Erin to Cowes where Shamrock II lay at anchor. Sailing over the Queen’s Cup course starting at the West Brambles and around the Warner and Lepe buoys, the wind was typical blustery Solent early-summer conditions and under the command of W.G Jameson, the Shamrock II came to the start line when a gust of wind caught her on starboard and, as a London Journal of the time reported, caused an incident which: “made Britain gasp.”

Shamrock II was fully dis-masted in under a minute. Fortunately, the King was sitting at the time of the incident at the top of the companionway, and once the wreckage was cleared and the crew all accounted for and rescued, went aft with a freshly lit cigar to enquire if anyone was hurt. The cause of the accident was said to be the breaking of the eye in the plate into which the bobstay was bolted at the stem and the rig and sails, having been cut away were subsequently salved by divers.

On May 23rd, 1901, Sir Thomas Lipton formally requested an extension from the NYYC of one month from the agreed America’s Cup start date of August 20th and even offered Shamrock I if the club found it: “must adhere to date.” Such was Lipton’s standing that the request was granted without question with much sympathy being passed across the Atlantic. Shamrock II was towed to the Clyde for a new mast and rigging but tongues were wagging with The Yachtsman, a respected British journal opining that: “Unless something is done in the way of alteration of design, we do not think the new boat stands the faintest chance for the Cup.”

Shamrock II was fast-towed by the steam-yacht Erin to New York via the Azores in just 16 days and laid up at Eerie Basin to receive her spars and rigging that were separately delivered by steamer. It gave the American public the chance to see the hull-form of a yacht that had been extensively tank-tested in model form at the Denny facility – a strip tank some 300 metres long and 10 feet deep. G.L. Watson had modelled some nine hull forms and the result was a finer shape, particularly at the bow than the earlier Shamrock I. In trials in American waters, Shamrock II was recorded as tacking in around 12 seconds and holding an upwind speed of 14 knots but this were to prove false data as she never attained such speeds in the Match itself, despite favourable conditions.

On September 24th, 1901, both Columbia and Shamrock II were measured at Eerie Basin showing the American boat to have a length at load on the waterline of 89.77ft as opposed to 89.25ft for the Challenger. Sail area was measured with Shamrock II setting some 14,027 square feet as against Columbia’s 13,211 and ultimately produced a 43 second handicap advantage to the Americans. This was ultimately to be an important margin.

With the spectator fleets manfully corralled by dint of the Order of Congress and patrolled by a fleet of six revenue cutters – the torpedo boats of 1899 were not required this time – the race for the America’s Cup got underway on the 26th September 1901 with some impressive moves in the pre-start. Captain Barr steering Columbia knew that he had met a match in Captain Sycamore, helmsman of Shamrock II but as he had done all summer against the Constitution and the Independence, Barr’s racecraft was to prove mighty.

At the start-line, Columbia secured a weather berth and a 12 second lead, back-drafting the challenger and deadening her progress in the water. As the race unfolded, and the winds began to die from the 12 knots at the start to just 7 knots by the mid-way point, Columbia showed a superior sail plan, deeper in its form and able to power away. However, with the fickle breeze, Shamrock II did manage to hold on and at one point on the second windward leg pass the bow and tack on top of Columbia only to be passed through the lee a few minutes later. By the final turning mark, the wind had shifted south and was dropping dramatically and at 4.40pm the race was declared void with Columbia ahead by over a mile.

The next meeting on September 28th 1901 began in nine knots of breeze and saw one of the greatest pre-starts ever seen as recorded in The Lawson History of the America’s Cup: “The great racing machines were tacked, jibed, and put about as easily as small raters, approaching each other within biscuit-toss, sometimes wearing ship in a complete circle in a diameter that seemed not greater than twice their own length, and moving all the time with the greatest ease and grace, under conditions of sea and wind that afforded an ideal setting for such a picture of modern racing of giant toys on summer seas.”

Shamrock II won the start and with the course being a straight windward-leeward, looked to hold all the advantage. Many boatmen of the day believed that winning the weather position off the line would win the race such was the blanketing effect that these goliath sea birds could throw off on the other, but Captain Barr on Columbia was anything but beaten and threw tack after tack at the Challenger with her well-drilled crew laid on the weather rail whilst Shamrock’s sat to leeward to increase the list.

By the top mark, Shamrock II had done what G.L. Watson, her designer, had hoped for and beaten an American yacht to weather, rounding 39 seconds ahead. If it were time however for celebration, the party would be short lived as Shamrock II luffed once around the mark to keep clear wind before setting spinnaker. Captain Barr was using every tick in his nautical armoury to try and trick the Irish yacht to set its spinnaker first but eventually bore away and set her billowing kite. Captain Sycamore followed suit but the distance that she had gained to weather was detrimental to course distance that now need to be sailed, with every boat-length counting. Columbia held the inside berth advantage and by half-way down the final run, was level with Shamrock II having feint chance of saving her 43 second time deficiency. With the wind dropping significantly, Columbia slipped through. By the finish she was ten lengths up and the record shows a corrected time win of 1 minute and 20 seconds.

After an abandoned race on October 1st, 1901, Sir Thomas Lipton wrote to the NYYC Committee suggesting that racing should take place on every day appropriate thereafter and this was granted in order to expedite the series. The next meeting on October 3rd, 1901, was set in almost perfect conditions with the wind at 10 knots at 10.00am and freshening. The course featured two beam reaches to start, followed by a weather leg and it was Shamrock II with its enormous sail area and innovative bow that seemed to lengthen the waterline in the breeze that not only made the better of the start, but held a lead to the final mark. In conditions that favoured Lipton’s yacht, its failure was in not capitalising on the advantage. Columbia held on for all she was worth, running down a deficit at the first marker buoy of 1 minute and 12 seconds to be just 42 seconds by the turning marker for the final leg.

Columbia’s upwind prowess combined with Captain Barr’s tactical nous saw her tack immediately off to port around the mark, opposing Shamrock II’s insistence on standing on, on the starboard tack. By splitting, Columbia forced a move and with pace she quickly closed the gap ending up on starboard tack to leeward of Shamrock II but able to power through her lee. When the two boats came back on port, having both overstood the finish, Columbia was well to weather and with started sheets they thundered towards the line. The Lawson History records that: “Columbia swept past the old yellow light vessel in a splendid burst of speed. Her buff decks glistened wet with foam and spray, her lee-rail was under pure green brine, and the golden afternoon sun lighted up in strong relief the distended surface of her pure white sails.”

It was 2-0 to the Americans, with the record showing a 2 minute 52 second win and 3 minutes 35 seconds on corrected time. Sir Thomas Lipton expressed keen disappointment in Shamrock II blaming its modelling over its handling by the sailors. The London press described the race as a “Homeric contest” and agreeing that Shamrock II was an “heroic failure”, but Lipton’s superb sailors were anything but quitters.

The final race of October 4th, 1901, was remarkable in the fact that it was the closest ever recorded in America’s Cup history to the date and was only settled on time allowance. Starting under huge clouds of canvas, the race got underway with Columbia obliged to start on the handicap gun which she did so late with Shamrock II following just 17 seconds later and both boats recorded as starting at the same time. Shamrock II with her sail plan advantage quickly passed Columbia and only an early unfortunate drop of her club topsail about a mile from the first turning buoy allowed the American boat to close the gap. At the turn, Shamrock II held a 49 second advantage but on the beat to windward opted not to cover Columbia as she headed inshore in better breeze whilst the Irish held off on port tack heading offshore. It was a first error. Columbia came back on port with better breeze and held the advantage but for the next three tacks it was too close to call between the two boats with either getting ahead as the wind puffed and faded around a 6 knot mean.

As the two Cup boats set up for a final leg to the line, both on starboard tack, some half a mile from the finish and within sight of dozens of steamers and excursionists, it was one of the most thrilling sights of the America’s Cup. The spectators held their breath as the boats thundered along, and with every passing passage of time felt the elation and deflation of their cheered-for boat as it seemingly gained or lost the lead. The Lawson History records that: “Their skippers sailed them as if for life or death, and as they neared the finish no man in the fleet could say which would snatch the wreath of victory.”

At the death, it was Shamrock II that crossed the line just two seconds ahead of Columbia but 41 seconds adrift on handicap. The America’s Cup was once again secure in the New York Yacht Club, but Sir Thomas Lipton was now more determined than ever to consider ways of “lifting the Cup”.