RANGER – THE ‘SUPER J’

Contractionary policies in response to what was an era of recession globally, leading to reduced aggregate demand and the fundamental cause of the Great Recession were hardly conducive conditions for the building of large race yachts.

It was thought that the J-Class could well sound the death-knell for the America’s Cup as a sporting contest and even the New York Yacht Club members, often insulated to a degree from the worst of the depression, were sailing smaller boats for club racing – most notably those rating to the 12-Metre and K-Class rules.

Against this dire economic backdrop, that incidentally was about to get worse through 1937-1938 before it got better, the Commodore of the Royal London Yacht Club, Richard Fairey, entered a speculative challenge - after surreptitious enquiries had been made - with a design that measured to the lower end waterline length permitted by the Deed of Gift and measure to the 65 feet New York Yacht Club rating rule. Not unreasonably, Fairey argued in a communication to Junius Morgan, Commodore of the NYYC, that: “I feel very strongly that the present J-Class boats are altogether too large and too expensive and that their design has been overshadowed by the necessity of fitting them out with accommodation for the owner and his guests when living aboard.” Further concerns surrounded the safety of the J-Class and whether they were suitable in anything above a Force 3 with particular note around the new duralumin rigs and their seaworthiness. The New York Yacht Club, however, were not in the mood to compromise on their premier competition.

Recognising this unwillingness and the rejection of the Royal London Yacht Club’s challenge, Thomas Sopwith commissioned Camper & Nicholson of Gosport to build what was hoped to be another technical wonder, Endeavour II, that was laid down in February 1936 and launched on 8th June 1936. Its flag was to the Royal Yacht Squadron but at the time of launch, no formal challenge had been proposed as both Charles Earnest Nicholson, the boat’s designer, and Sopwith felt that a long period of working up and crew training would be the key to a successful challenge. That challenge was duly posted to the NYYC by August 1936 for the Endeavour II rating to the 76-foot rating rule as recognised by America’s premier club and seeking for racing to start in July 1937.

Early assessment of Endeavour II was mired by the collapse of two masts, but the Americans were concerned by the seemingly devastating performance of the boat against Endeavour I in light airs, where it was widely assumed that she had a significant advantage over the successful defender of 1934, Rainbow. The New York Yacht Club formed a syndicate again under the command of Harold ‘Mike’ Vanderbilt who duly commissioned Starling Burgess as lead designer but also made the crucial decision to create a design team by bringing onboard the fast-rising star of yacht design in Olin J. Stephens. Burgess’s star had been falling for a while in the eyes of the members of the New York Yacht Club with the view, widely expressed, that the speed deficiencies of Rainbow and Enterprise were only rectified by the brilliance of Vanderbilt, Bliss and Hoyt in the afterguard. Bringing Olin Stephens in was a nod to the future and a check on Starling Burgess.

Tank-testing was nothing new in the America’s Cup, G.L Watson was tank-testing in 1900, but the advance in the way those tests were undertaken, and the data extracted, particularly in terms of heel angle and side force, saw the 1937 design project for Ranger advance yacht design to a whole other scale. Using the Stevens Institute testing tank at Hoboken under the command of Professor Ken Davidson, Stephens and Burgess both drew lines for two models each to be tested. The final design for Ranger has, however, become something of legend with no clear view on whether it was from the hand of Burgess or Stephens as the models were adapted during testing with input from both, but what became evident was that the result was a sensation.

Olin’s brother, Rod Stephens, was brought in for the design of the rig whilst Starling’s brother, Charles Burgess, took charge of the mast design. These were crucial areas as Vanderbilt insisted on using some sails from the Rainbow campaign – in particular an unused mainsail that he had been saving – and much concentration was given to more efficient sail-handling. Meanwhile, the final design for Ranger’s hull profile had the mark of Olin Stephens writ large with a low aft profile and the famous snub-nosed bow whilst Vanderbilt himself had considerable input in the final waterline length of 87 feet having seen a marked improvement in 1936 when he added a 10-ton lead shoe to Rainbow’s keel for the annual New York Yacht Club cruise races.

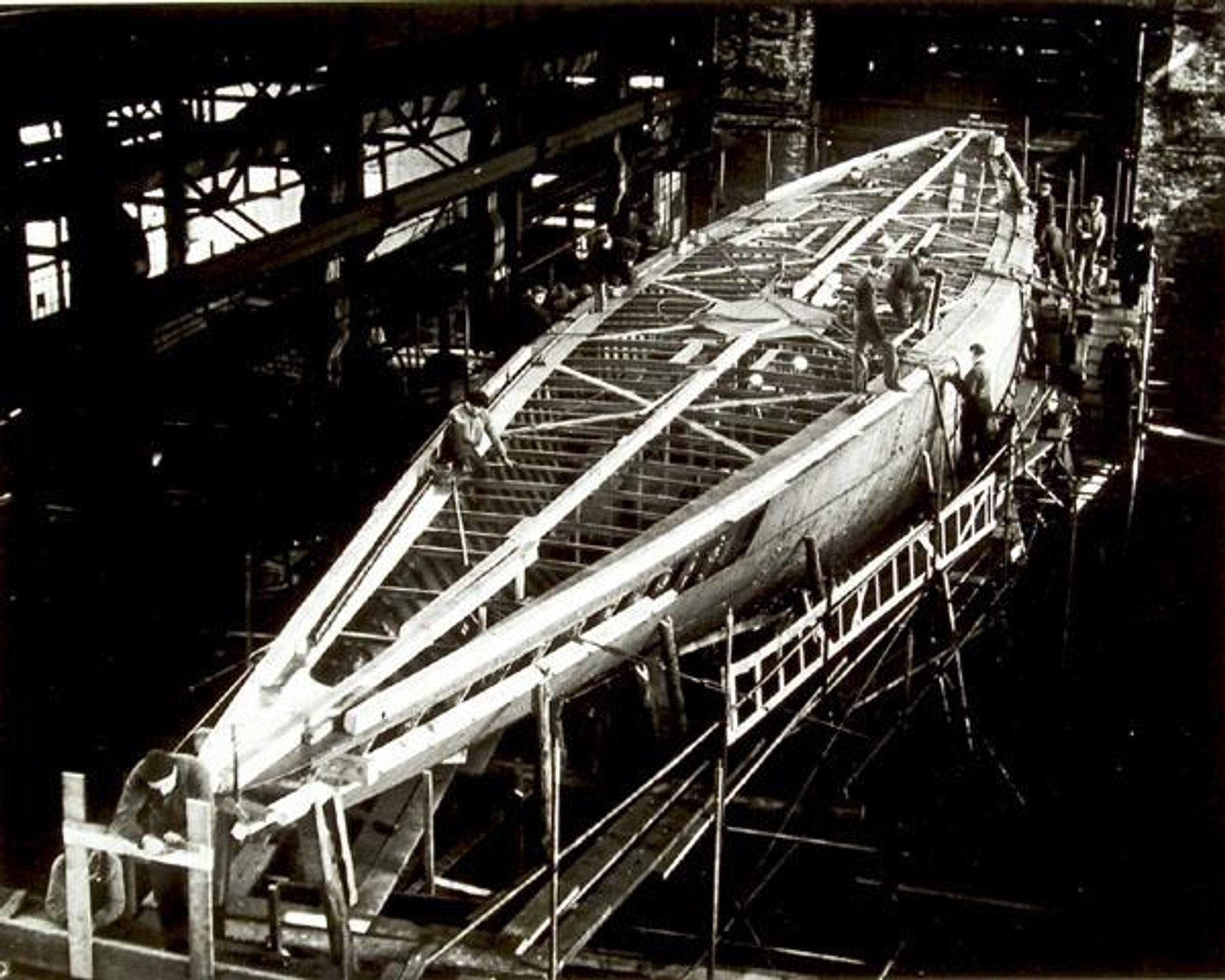

The final model that produced the design was number 77-C, one of the first tested, and the Bath Iron Works Boatyard was commissioned for the build, but worsening economic climes caused Ranger to be built at cost using highly efficient construction methods. Filler was almost eliminated in the process with flush riveted steel plating forming the hull and cedar was laid on steel for the decks to reduce both weight and cost. The designers went novel for the rudder creating a negative buoyancy structure with a watertight air compartment and a very low clearance to the hull and Ranger was launched on May 11th, 1937, after a christening ceremony with Mrs Gertrude Lewis Vanderbilt (nee Conway) breaking the customary champagne on the snub bow.

Just like the problems on Endeavour II, Ranger experienced a mast failure on its tow down from Bristol, Maine in a heavy seaway thus proving the fragility of the duralumin masts as feared and in a race against time, the old 1934 mast of Rainbow was stepped whilst a replacement was re-fabricated. At this time, in May 1937, Endeavour II arrived in Newport under tow having sailed the last 720 miles owing to a significant Atlantic storm – remarkably she arrived unscathed minus some rusting on the spar.

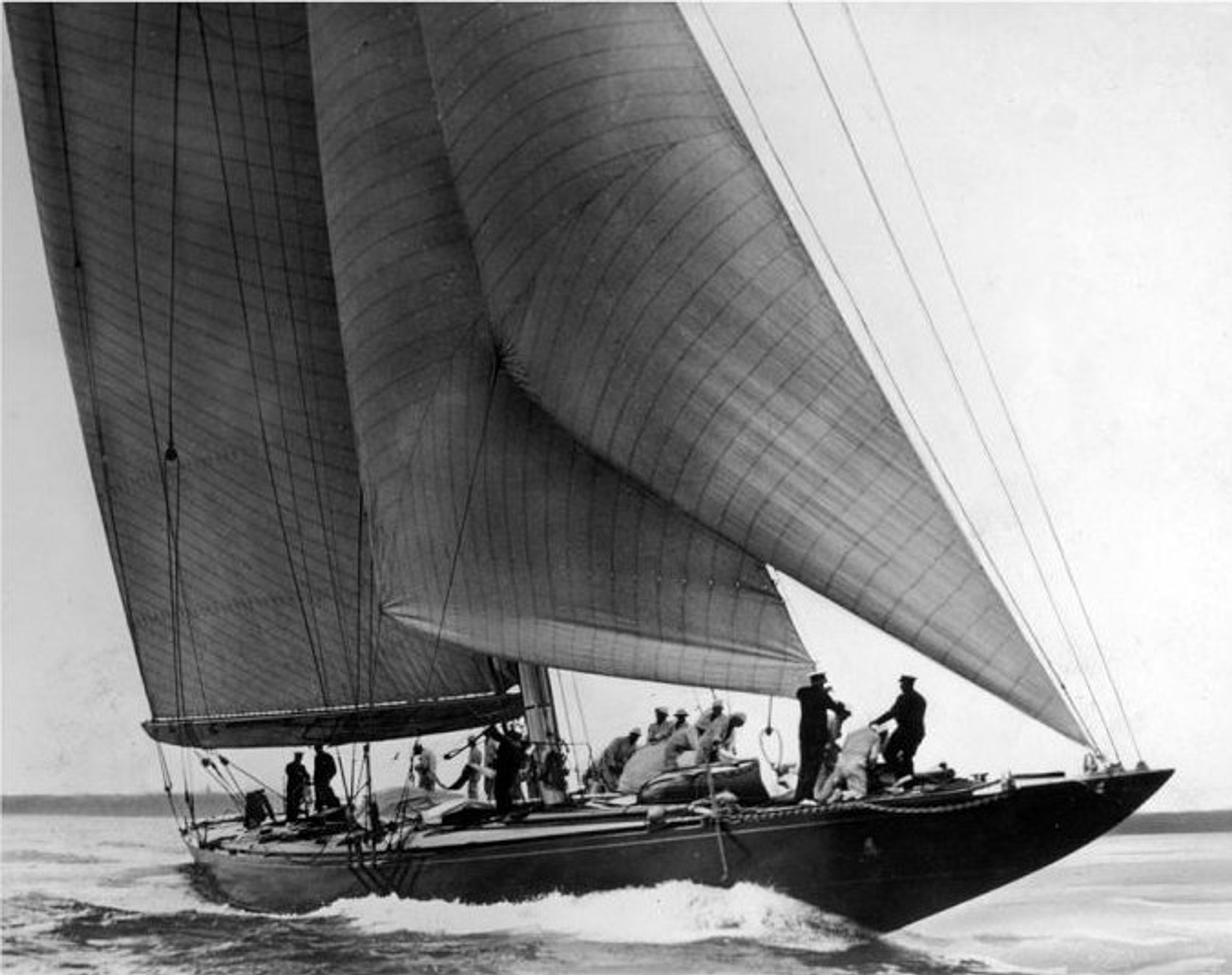

Ranger’s preliminary races against Rainbow and Yankee proved that she was a rocket-ship of sorts. Stiff, fast and devastating on a reach, she won each of the three races and entered the defender trials with the notion that she was ‘unbeatable’ – and by the time her replacement mast was stepped, and the old 1934 sails replaced by modern ones, the trials were to be a one-sided affair. Indeed, in one race against Yankee when Ranger won by a massive margin, she did so at an average speed of some 11 knots and set the fastest recorded time ever over the America’s Cup course. The omens were good for a successful defence and Ranger was appointed without question by the New York Yacht Club committee.

Endeavour II’s work-up that summer was almost solely against Endeavour I in a series of practice sessions that roused both suspicion and derision by the yachting journals in America. Sopwith was obsessed with speed trials and manoeuvres, setting exactly the same sail plan on both boats and then proceeding through a set of drills before long runs on opposite tacks before coming back together and then halting the session. De-briefings were long, and crew-work was honed as the memory of poor sail-handling in 1934 was sought to be avenged. Endeavour II was observed by the Americans as being faster on all points of sail than her much-admired predecessor and on July 1st, 1937, the Royal Yacht Squadron confirmed to the NYYC that Endeavour II would be lining up as challenger for the America’s Cup (there was a thought that Sopwith might try and swap out Endeavour II for Endeavour I but this pure media speculation).

Could she match the pace of Ranger though who had spent that summer on their sail wardrobe and in typical Vanderbilt fashion, sought improvements all over?

Ranger’s sail inventory that summer was the most remarkable seen on a J-Class to date. The introduction of the enormous 250%, 175% and 135% quadrilateral jibs that were set over over-sized staysails that had been tacked further forward to produce an effective ‘slot’ gave Ranger power unseen before on these boats – and a commensurate beefing up of winches and blocks to cope with the loads was thoroughly worked up through that summer after notable failures in the trials. Vanderbilt was convinced that as much as the waterline length had been a determining factor in 1934, that in 1937 the major gains would be made aloft. Ranger’s mainsail inventory included one from Enterprise of 1930, updated by the City loft of Ratsey’s, a staysail from Vanderbilt’s M-Class ‘Prestige’ and great advances were made both in the spinnaker design, particularly the ballooner, and in how they were handled in manoeuvres. Vanderbilt even mastered a way of gybing with the spinnaker left up that was ultimately outlawed for 1937 but became standard thereafter.

By contrast, Endeavour II’s sail programme had seemingly not advanced from the standard plans of Endeavour I in 1934 and the early loss of two masts in early trials led to caution creeping in on Sopwith’s behalf to push the rig development. It was a fatal error in competitive terms but both boats came to the start of the America’s Cup in 1937 wary of the other and after such a close fight in 1934, the American media assumed that this would be a desperately closely affair once more with some even arguing that a Cup abroad would be good for the future of the sport.

The first race dawned with very light winds on July 31st, 1937, causing the race committee to postpone for 45 minutes to allow the expected breeze to fill in for the planned 30 mile windward / leeward test. Endeavour II got the better of the start, crossing the line ahead by three seconds to leeward of Ranger and able to squeeze up, forcing Vanderbilt to tack away for clear air after 11 minutes.

With clear wind now, and despite Sopwith throwing in a tack to try and cover, Ranger just eased away with Vanderbilt steering loose for speed before coming back to course and after an hour of sailing had left the English challenger almost a mile dead astern. With the breeze freshening, both boats called for a sail change. Vanderbilt was getting increasingly uncomfortable with the 250% quadrilateral in an un-tested wind-range so called for the 175% quadrilateral but the crew, in error, launched the 135% and with Endeavour II swapping from genoa to 175% quadrilateral, for a while the American skipper, although with a healthy lead said that Ranger felt “dead in the water.”

By the top mark, Ranger had clung on and rounded with a lead in excess of six minutes and launched a balloon jib with a light staysail as the wind backed. Sopwith was in gambling territory and sailed high once around the weather mark on the thinking that the incoming breeze with layers of mid-fog would back the breeze further. In short order, the two boats lost sight of each other and as the wind came aft, Ranger launched a light parachute spinnaker formerly seen onboard Yankee and romped home. The margin was astonishing – 17 minutes and 5 seconds – and Endeavour II was in danger of missing the time-limit. Spectators, that numbered some 300 craft of all shapes and sizes, had never seen anything like it in the modern America’s Cup. The early writing was on the wall for the Challenger.

A fresher breeze awaited the yachts for race two with a triangular course set and it was Endeavour II that again made the better start. The practice that Sopwith had executed in the tune up with Endeavour I paid handsomely at close-quarters and a tack beneath Ranger in the dying moments of the pre-start was a textbook move. Ranger, now sitting in backwind dirty air was forced to tack off onto port soon after the start but on the tack back to head out to the left of the course, a top block for the quadrilateral sheeting position exploded and the crew struggled to get optimum trim.

Endeavour II was looking good to maintain her lead and at various points of the first leg she could have easily tacked and crossed, but the race was about to be turned on its head as the English sailed into a light, heading patch of breeze that slowed her dramatically. Ranger came up astern, hit the same pattern and immediately Sopwith tacked in the hope of getting up to speed and crossing the Americans’ bow. Vanderbilt maintained better speed and seeing the English dead in the water, tacked with way under her to leeward and with better crew-work emerged with pace on port tack. Pretty soon Ranger was eking up onto Endeavour II’s line, forcing her to tack off and it was one-way traffic. Ranger extended on the second half of the beat to round 10 minutes 25 seconds up.

With her 250% quadrilateral set – a sail that was nicknamed the ‘Mysterious Montague’ for its inherent cloth being specially developed by DuPont DeNemours Company with rayon and a special coating of aircraft dope – Ranger extended on both reaches of the triangular course. Sopwith had no answer for her waterline speed and superb sail inventory and the winning margin of 18 minutes and 32 seconds was another hammer-blow to the English who simply couldn’t match the super-J creation of Vanderbilt, Burgess and Stephens.

Sopwith called a lay-day to haul Endeavour II out of the water, convinced that she had damaged her centreboard through tangling with a lobster buoy or some other object under the water, so inexplicable was the speed loss on that first beat. “Ranger was pointing much higher, and we could not point any higher than we were. We lost 10 minutes in 5 miles. It is possible we picked up one of those lobster pots,” Sopwith commented afterwards whilst also insisting that some 5,070 pounds of lead were removed from the ballast to improve the light-weather performance. It was time to gamble.

Race three, always a crucial race in these first to four America’s Cup battles where the pendulum can swing or momentum can be carried forward, was do or die for Sopwith but Vanderbilt, smarting from the Dailies taking issue with his starting prowess was more than up for the fight. The windward / leeward course was set in a steady 10 knots of breeze, and it saw the two magnificent J-Class yachts circling aggressively in the pre-start before heading to opposite ends of the start-line on opposite tacks at the gun. Vanderbilt aced the start at the leeward end on starboard tack whilst Sopwith came across 18 seconds down at the other end on port. Sopwith certainly felt that with the reduced ballast, he had the measure of Ranger in a tacking duel and initiated the play which resulted in Ranger’s winch jamming again forcing the quadrilateral sail to be mis-sheeted halfway up the beat.

The wind Gods of Newport however saved the day for Vanderbilt as she sailed a few degrees off the wind but into a favourable shift, keeping Endeavour II on her stern, that allowed Ranger to tack and sail into a lead of 4 minutes and 13 seconds at the top mark – incidentally the fastest recorded time for a 15 mile beat to windward in America’s Cup history.

A split decision upon rounding the windward mark saw Ranger gybe off immediately whilst Endeavour II bore away onto the port gybe with both boats setting spinnakers as the wind increased to 14 knots. For the next 14 miles the boats converged on opposite gybes with Ranger holding the lead but Endeavour II looking the more likely to maintain a direct line to the finish without the need for the costly manoeuvre of gybing. A wind-shift, just a mile from home however, scuppered any chances and both boats were forced to gybe to make the finish with a shy reach to the line calling for a ballooner to be re-launched on the new gybe on both boats. Ranger held on and crossed with a 4 minute 7 second delta and it was match-point to the Americans.

For what proved to be the final race of the America’s Cup in 1937, and in fact the last time that the regatta would be run for the next 21 years, it failed to live up to its billing and an English fight-back was scuppered when Sopwith went over the start-line early. Aggressive tactics from Vanderbilt in the final circle saw Ranger trapping Endeavour II forward and with nowhere to run, she was forced over and Sopwith had to dial away into a gybe and re-cross, losing a minute and fifteen seconds in the process.

Ranger was now unstoppable, sailing in clear air, and matching Endeavour II tack for tack with no discernible loss of speed in the fresh breeze. Vanderbilt had insisted on setting a flat-cut mainsail from the 1930 wardrobe inventory of Enterprise and it was a masterstroke. By the windward mark she was 4 minutes and 5 seconds up and with her 250% quadrilateral set, she powered to the wing mark and despite Endeavour II shaving 30 seconds on that leg, the two boats were even on the final reach to the finish, and it was a resounding win to the Americans of 3 minutes and 37 seconds.

At the finish line, Vanderbilt handed the wheel to Olin and Rod Stephens to cross in a remarkable gesture of recognition at their efforts in producing what was undoubtedly the finest yacht in the world at the time – and considered even today, as the greatest yacht ever to compete in the America’s Cup. She was a marvel of the age and a testament to American design, astute build in strained financial times and Vanderbilt’s undeniable prowess at taking a boat to its racing limits. In subsequent races that summer, she was untouchable, beating all-comers and stamping her authority on the global yachting scene as the marker by which the era would be judged.

For the English it was another disappointment. It was to be T.O.M. Sopwith’s last hurrah in the America’s Cup but he was proud of his efforts saying: “We have had a series of the most wonderfully close races and I find the greatest difficulty in expressing my gratitude to our crew, amateur and professional, for the wonderful work they have done – they have all worked like slaves. May I say that we are not downhearted.”

The America’s Cup in 1937 was the last of the J-Class in the competition. With a pause for the Second World War, the next regatta in 1958 would see the 12-Metre rule adopted and the graceful lines of some of the most iconic yachts ever created would forever more be for the history books or those with deep pockets in modern times to restore, re-build or recreate those fabulous yachts. Only ten J-Class yachts were built, six in America and four in Great Britain, although several boats of the ‘big class’ of the era were adapted to conform to the J-Class rule. It was truly a ‘golden era’ and one that put the America’s Cup very much at the pinnacle of the yacht racing world.

WITH WORLD WAR II LOOMING, THE AMERICA'S CUP WENT INTO A HIATUS AND EVENTUALLY CONTINUED IN 1958