CUP RACING RESUMES AFTER THE SECOND WORLD WAR

As history would prove, the 1937 regatta and the all-conquering display by Harold Vanderbilt and the Ranger campaign was the full-stop on what became known as the ‘Golden Era’ for the America’s Cup. Dark clouds of war once again descended on Europe and enveloped the world between 1939-1945 leaving behind a fiscal environment that made the money-no-object J-Class yachts out of the reach of even the richest.

Chastened times post 1945 led to a complete lull in will for racing for the Cup so it wasn’t until 1948 when discussions began again about the possible resurrection of the competition. A meeting was held between the Commodore of the New York Yacht Club, De Courcey Fales, and Captain John Illingworth, the Commodore of the Royal Ocean Racing Club to consider the possibility of introducing an international cruiser-racing rating rule for the competition with yachts of a 48-foot waterline, but these talks ultimately stalled. (Illingworth rather famously went on to create the Sydney-Hobart yacht race.)

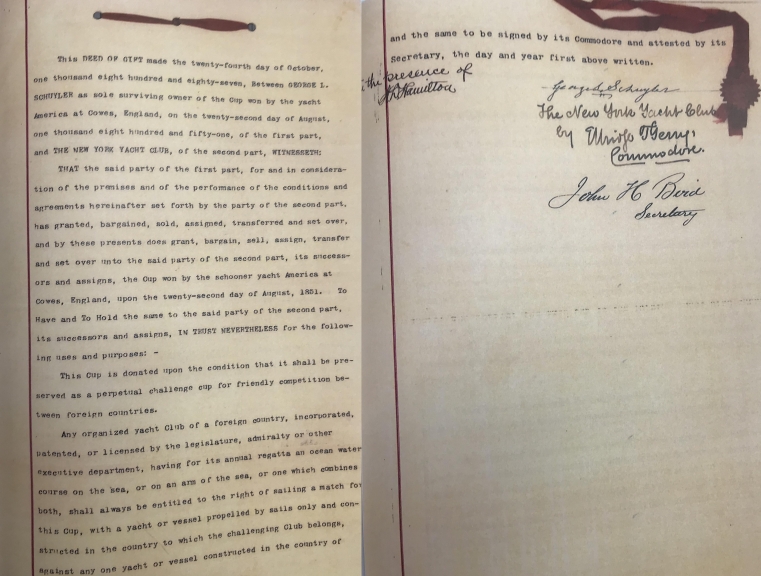

A further seven years passed as the world economy struggled back to life post war, before Henry Sears, the then Commodore of the NYYC visited Britain to meet with his opposite number at the Royal Yacht Squadron, Sir Ralph Gore, and after much discussion, Sears returned to America with an idea to revive the America’s Cup that would require a change in the Deed of Gift. The Squadron and its sub-committees had been clear to Sears that the America’s Cup was a special event and as such should continue to feature yachts built for the event and the format. Both the Squadron and the NYYC were attracted once again to the pre-war notion and suggestion (that had been discarded rather vociferously) of sailing in the 12 Metre Class but as the last surviving members of the original trust deed had long since passed, an application to the New York Supreme Court would have to be instructed in order to take the waterline length requirements down from 65 feet minimum to 44 feet.

For Sears, this wasn’t an easy negotiation back home with a shifting groundswell of opinion amongst the membership of the New York Yacht Club. Some wished for the competition to cease and the trophy to simply remain as a memento in the clubhouse of a glorious era, whilst others designed that it should be contested by nominated clubs in America and thus reduce the burden on the membership to put up for its defence. Sears steered a politically cautious route through the opposition and filed a petition to the courts on 21st September 1956 seeking to alter not only the waterline length but also the prohibitive requirement that a challenger must arrive on its own bottom. The die was being cast for the modern-day America’s Cup and on the 17th December 1956, the Supreme Court of the State of New York issued an ‘Order with the Respect to Administration of Gift’ and granted the requests.

Furthermore, an additional ‘Protocol in Resolution’ was adopted by the Board of Trustees of the Cup on 27th March 1958 that redefined the language used in the third Deed of Gift of 1887 with its stipulation for challenging and defending yachts being constructed in the countries they respectively represent. This protocol clarified that wherever the word “constructed” appeared in the Deed of Gift it was to be construed as “designed and built” – wording that would prove of high importance in subsequent challenges and the recent history of the America’s Cup.

With the issues around the Deed of Gift settled, momentum built in early 1957 for a British challenge from the Royal Yacht Squadron and no less than four naval architects were appointed to submit models for testing at the tank at Saunders-Roe in East Cowes on the Isle of Wight. The models all conformed to a one inch to a foot scale, considered with hindsight to be inconclusive and inconsistent, and the results were evaluated by a technical group consisting of such luminaries as Frank Murdoch, the technical adviser to T.O.M. Sopwith on two Endeavour campaigns, Olympic silver medallist Lieutenant Colonel ‘Stug’ Perry, William Crago the superintendent of the Saunders-Roe tank facility and Hugh Goodson, the appointed Royal Yacht Squadron syndicate head. Their findings were presented to the nine founding members of the Squadron syndicate with a recommendation that the design by the Scottish naval architect David Boyd be selected and that the contract to build the 12-Metre be awarded to Alexander Robertson and Sons of Argyll in Scotland.

Constructed under the patriotic but ultimately bland name of Sceptre, this was the first 12-Metre built in the world in some nineteen years and as such faced considerable fit-out issues around deck hardware and fittings. Everything had to be machined virtually from scratch whilst crew input into deck layout was rooted in old thinking and only the ingenuity of Boyd saved the day, in particular with the low cockpit that kept the crew out of the wind and spray.

Over in New York, a powerhouse committee of Cup winners had been formed with such names as Harold ‘Mike’ Vanderbilt, Henry Morgan, George Hinman, Bubbles Havemeyer and Luke Lockwood appointed, and no less than three 12-Metres planned as well as the refurbishment of Olin Stephens’ 1939 built ‘Vim’ which had proven such a weapon in club racing. Of the new boats, Columbia, again off the drawing board of the star designer of the day in Stephens was built at City Island for a syndicate comprising Henry Sears and Briggs Swift Cunningham and was regarded as the boat to beat. Weatherly with Ranger’s sail trimmer, Arthur Knapp Jr. as helmsman, and Easterner owned by Chandler Hovey were also commissioned and launched that summer whilst onboard Vim, the likes of Ted Hood, Bus Mosbacher and Donald Mathews posed an afterguard of great talent.

The Cup being the Cup, and the desire to find an advantage ever-present, saw the introduction of Dacron sails for the first time whilst Zeta nylon was developed for the spinnakers by the Ratsey loft in America – very much the sailmaker of the time. The Defender series was a long summer, but the versatility of 12-Metre racing was very much proven. As it turned out the boat to beat was Vim, something of a surprise to both the yachting media and the establishment, but she traded blows with Columbia all summer long and by mid-August 1958 there was no doubt in the NYYC Committee’s mind that this was a two-horse race. With Sceptre loaded aboard the freighter Alsatia and in transit on its way to Newport, the final trials were scheduled for September 1958 in an attempt to replicate the conditions as closely as possible to those that would be met in the Match.

The four defending yachts entered an intense period of racing with Columbia proving to be the boat that had the most potential, most notably when the breeze was up, and after Weatherly and Easterner were eliminated jointly, the Committee held a six-race series between Vim and Columbia to decide their selection. Vim with the brilliant Bus Mosbacher on the helm was arguably the better boat in moderate conditions but, with a scoreline of 4-2 at the end, it was Columbia that was duly selected.

In reality there was little to choose between the two boats but Columbia prowess in anything above 15 knots of breeze was a considerable advantage as she could point higher and hold her position to windward better than anything seen before. A notable scribe, William H Taylor, writing in the autumn edition of the Yachtsman noted: “When Olin Stephens tried Columbia’s model in the tank last fall, he was convinced he had a faster boat but took all summer to prove it.”

Whilst Columbia came on strong through the season, Sceptre’s trials back in Britain were underwhelming with the new-build being beaten on a regular basis by a decent crew onboard Evaine, the pre-war 12-Metre of the legendary Owen Aisher, that was often steered most ably by the newly knighted Sir T.O.M. Sopwith (he was knighted in 1953). Recognising that Sceptre was under-crewed, the Hugh Goodson led syndicate appointed the bronze medallist from the 1956 Olympic Games in Melbourne, Lieutenant Commander Graham Mann as skipper and recruited Stan Bishop from Evaine as the crew captain.

Sceptre was upgraded in the early summer with better genoa winches and mainsail controls – they only fitted a kicking strap at the end of June 1958 – and slowly her speed started to show through against the much older Aisher-owned 12-Metre. One area of notable deficiency however was in spinnaker development with the British persisting with the enormous Jean-Jacques Herbulot designs that were set at the maximum with spans of 92 feet and a sail area of 5,570 square feet whilst the Americans had spent considerable time developing narrow, more efficient kites that were felt offered better control and were easier to use through manoeuvres.

On arrival in Newport on August 12th, 1958, Sceptre entered in to some tune-up trials against an even older 12-Metre, Gleam, loaned by Mahlon Dickerson, Secretary of the NYYC and steered by Owen Aisher but this was of little use in developing the challenger. Gleam struggled to keep up and in order to engage in any meaningful way, Sceptre had to back off and at times the crew were trailing warps and buckets to slow down whilst Gleam was turning on their engine to catch up. In essence, the trials were pointless, and she entered the America’s Cup Match that summer deeply unprepared and thoroughly untested against meaningful opposition.

Download the 1958 America's Cup Programme

The conflicting views of the America’s Cup and its place as a sporting contest continued to rumble through that summer and much was made in the media of the move to the 12-Metre class. Even Harold ‘Mike’ Vanderbilt wished it away saying: “We have kept the Cup for over 100 years, and I would like to see it go, so that we could go overseas to regain it.” But with President Dwight Eisenhower watching the opening race on the 20th September 1958, many viewed Vanderbilt’s assertion with some scepticism and as the racing would prove, this was to be one of the most one-sided contest in the Cup’s history.

Opening races of America’s Cup Matches, particularly the first beat to windward, are when the talking stops and answers are offered. It’s the point where many yachting scribes and observers say: “we know,” and so it was on that September day in light and fickle breeze as Columbia lined up to leeward of Sceptre, with Briggs Cunningham on the helm sailing fast and loose, and powered out to a lead of 300 yards in just 10 minutes. From there she was never headed, rounding the top mark on a twice-round windward-leeward course some 7 minutes 36 seconds ahead after just six miles.

With desperately light airs across the racecourse both boats struggled to set spinnakers, Sceptre’s troubles were more pronounced with her unwieldly Herbulot which she changed for a smaller one when headway suffered and then switched back to another Herbulot in the final approaches to the leeward mark. Sceptre had gained by mark two to round just over 2 minutes astern but a windshift turned the next leg into a shy reach under genoa and Columbia streaked ahead to round mark three with a lead in excess of 8 minutes. In distance terms it was over a mile and the 1500 strong spectator fleet laid witness to a slaughter on the water – Sceptre was just no match for the design and innovative sail-plan of Columbia. By the finish gun it was a resounding 7 minutes and 44 second victory to the Americans.

After an abandoned race and a subsequent lay-day called by Sceptre’s skipper Graham Mann in order to not only haul out the challenger and pay attention to the hull finish but also to receive a new suit of sails from the City Island Ratsey loft, racing resumed on Wednesday 24th September 1958 on a triangular course. If hopes were set high on the British challenger that the improvements introduced would close the gap, they were sorely dashed in an almost demonstration race.

Columbia started to windward, in a building 8-10 knot south-south-westerly, and a favourable shift almost immediately laid them to the top mark with only a short tack required to round with a lead of over three minutes. The reach to the wing mark saw the Americans launch the spinnaker that they had nicknamed ‘Big Harry’ – a big reaching kite borrowed from the ‘Vim’ campaign and simply sailed away, rounding some 8 minutes 55 seconds up with just one long reach to the finish. Sceptre rolled the gambling dice on the final leg, dropping her spinnaker and reaching high but it was a foolish bet and by the finish ended up over two miles astern in the haze as the Americans recorded an 11 minutes and 42 seconds victory. 2-0 and the writing was on the wall once again for the British in conditions that should have proven favourable.

Keen to conclude the series, the New York Yacht Club sent the boats out on Thursday 25th September 1958 in a blustery 20 knots that was forecast to rise through the afternoon and a lumpy sea state. This was to be an interesting test for both boats with the British feeling that their attention to bespoke deck hardware, in particular the genoa winches, could pay dividends whilst the Americans were keen to see how Columbia fared in rougher conditions. The Race Committee laid a course of six mile windward-leeward legs, twice around and off the start-line, both boats were equal with Sceptre to windward and holding her own in point to the Americans.

Graham Mann was known for pinching high whilst Briggs Cunningham had a gentler style of building speed and power, and pretty quickly it became obvious that Columbia was faring better in the sea state. Sceptre’s pitching was having serious speed implications and the only option for the challenger was to initiate a tacking duel. Pleasingly for the British they found that their manoeuvres were slicker, with the genoa coming in noticeably faster, but the pitching made building speed post-tack an issue. Columbia weathered the 18-tack duel and rounded with a healthy 2 minutes 23 seconds lead.

Both boats thundered downwind with the breeze building and by the leeward mark, Columbia had made a modest six second gain before rounding up into a solid 26 knot breeze. It was to be her finest moment, and conditions where throughout the summer the Americans had excelled. The challenger had no answer to her pace and power, in particular her purple coated Dacron mainsail known as the ‘Purple People Eater’ and she sailed off into an unassailable lead of 7 minutes 45 seconds at the final windward mark.

By the finish, with ‘Little Harry’ set – a slightly smaller spinnaker – Columbia extended to 8 minutes and 20 seconds with the challenger deflated and discouraged. Coming ashore, analysis was offered that suggested Columbia held an advantage of 4.4% over Sceptre and yachting circles in Britain were already bemoaning the challenge, pointing towards the tank testing inefficiencies that had produced such a woeful and embarrassing challenger.

With that in mind, race four was again a one-sided affair in 21 knots of breeze where Briggs Cunningham, Columbia’s skipper, opted for the rare tactic in match-racing of refusing to cover a rival, preferring to sail off knowing that speed was inherent. There was little the British could do, every time they came back on course, Columbia had extended, and Sceptre’s only perceived advantage in better sail-handling was completed negated. On a triangular course, Columbia rounded the windward mark with a five minute and 30 second advantage that she stretched out to 8 minutes and 13 seconds at the wing mark. The final leg was shy due to a windshift approaching the wing, and both boats hoisted genoas. By the finish gun it was a 7 minutes and 5 seconds victory to Columbia and the America’s Cup was safe once again the New York Yacht Club’s possession.

The aftermath of the 1958 Cup races was particularly brutal for the British, with blame being laid at the door of Sceptre’s designer David Boyd, the tank-testing at Saunders-Roe, and the Royal Yacht Squadron syndicate led by Hugh Goodson. The New York Times featured an article by John C. Devlin that called Sceptre: “as pretty and as lovely as a ballet dancer and as clumsy as an oaf with a hangover.”

With true British style, the yachting establishment offered no recriminations against the sailors, designer or builders preferring to learn their lessons and move on quietly. And rather classily Hugh Goodson, responding to questions about whether they would be back in the America’s Cup, offered a line that still hold true today for British challengers: “Quite frankly, I doubt that we shall ever give up.”

READ MORE ABOUT THE 1962 AMERICA'S CUP: ENTER THE AUSTRALIANS