BUILT TO RACE

Most notably, the challenge of 1881 saw the beginnings of boats being built specifically for the defence of the America’s Cup – although in this particular series, despite a new boat being constructed in the 72ft 6in centre-board sloop Pocahontas, it wasn

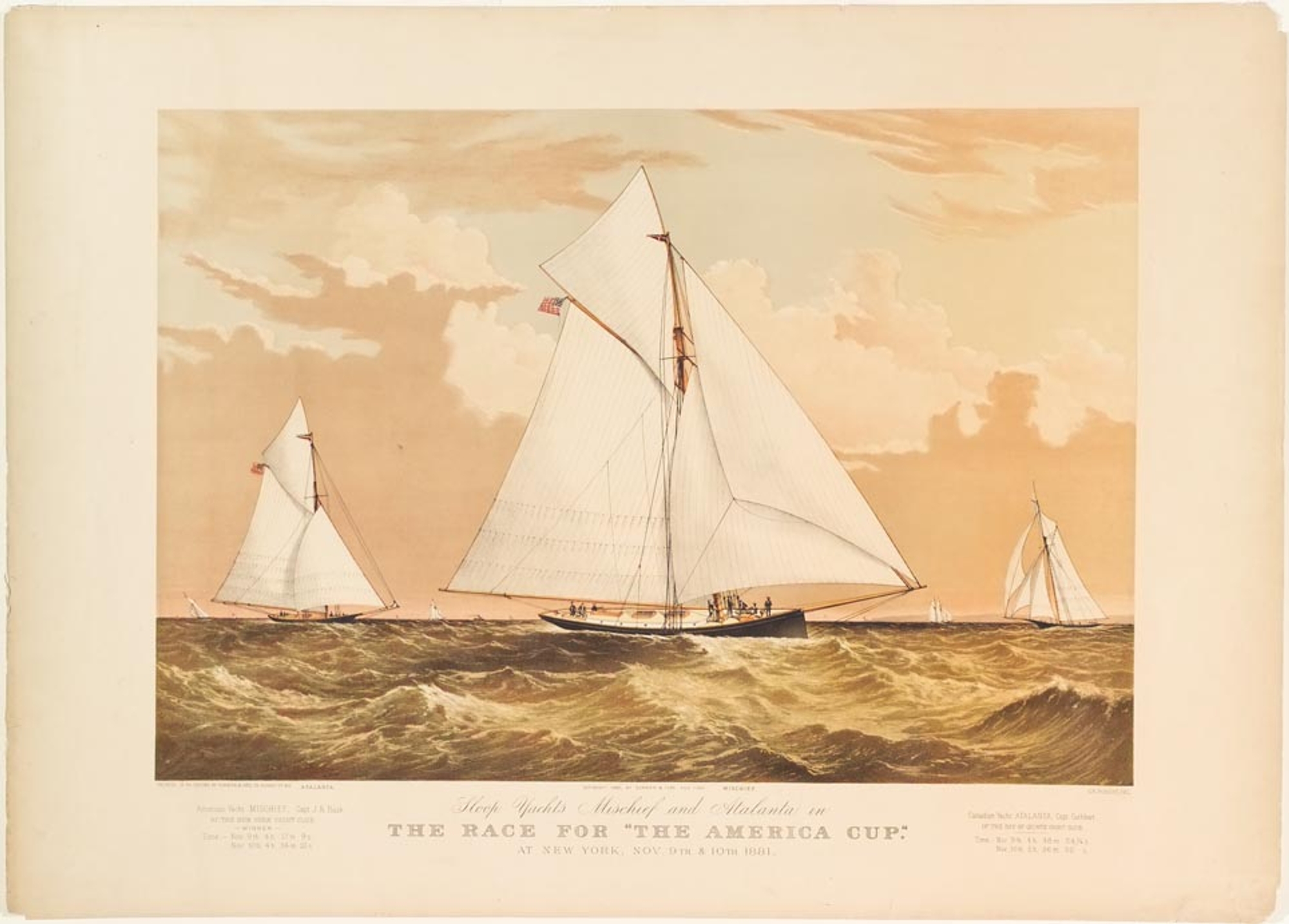

The defence was placed in the hands of the ‘Mischief ‘which was something out of the ordinary as being only the second ever metal boat built in the USA, the first made of iron to defend the America’s Cup, and having an Englishman owner, Mr J.R. Busk, who was a member of the NYYC. Nationality aside, the Mischief was selected amidst an acrimonious final trial over Charles R. Flint’s sloop, Gracie.

Ahead of the racing for the Cup against The Atlanta, the 67ft 5in Mischief was hauled out and as the Lawson records: ‘her underbody was sand-papered, holystoned, varnished and pot leaded, until it shone like platinum.’ She was a water-shed boat in Cup defences, being scientifically built rather than to the eye of the wooden yacht craftsmen and led to new construction methods being adopted going forward despite being two years old by the time she defended the Cup.

And defend she did, the Mischief romped away in a two-race series that was described as a ‘procession’ in the journals and failed to rouse much interest in the New York locals, so sure were they of a thumping victory. The margins of victory on corrected time were 28 and 39 minutes in the two races respectively and despite Captain Cuthbert wanting to winter in New York and challenge again in the following year with Atlanta, the new Deed of Gift subsequently precluded this, and she returned to Lake Ontario to compete successfully there.

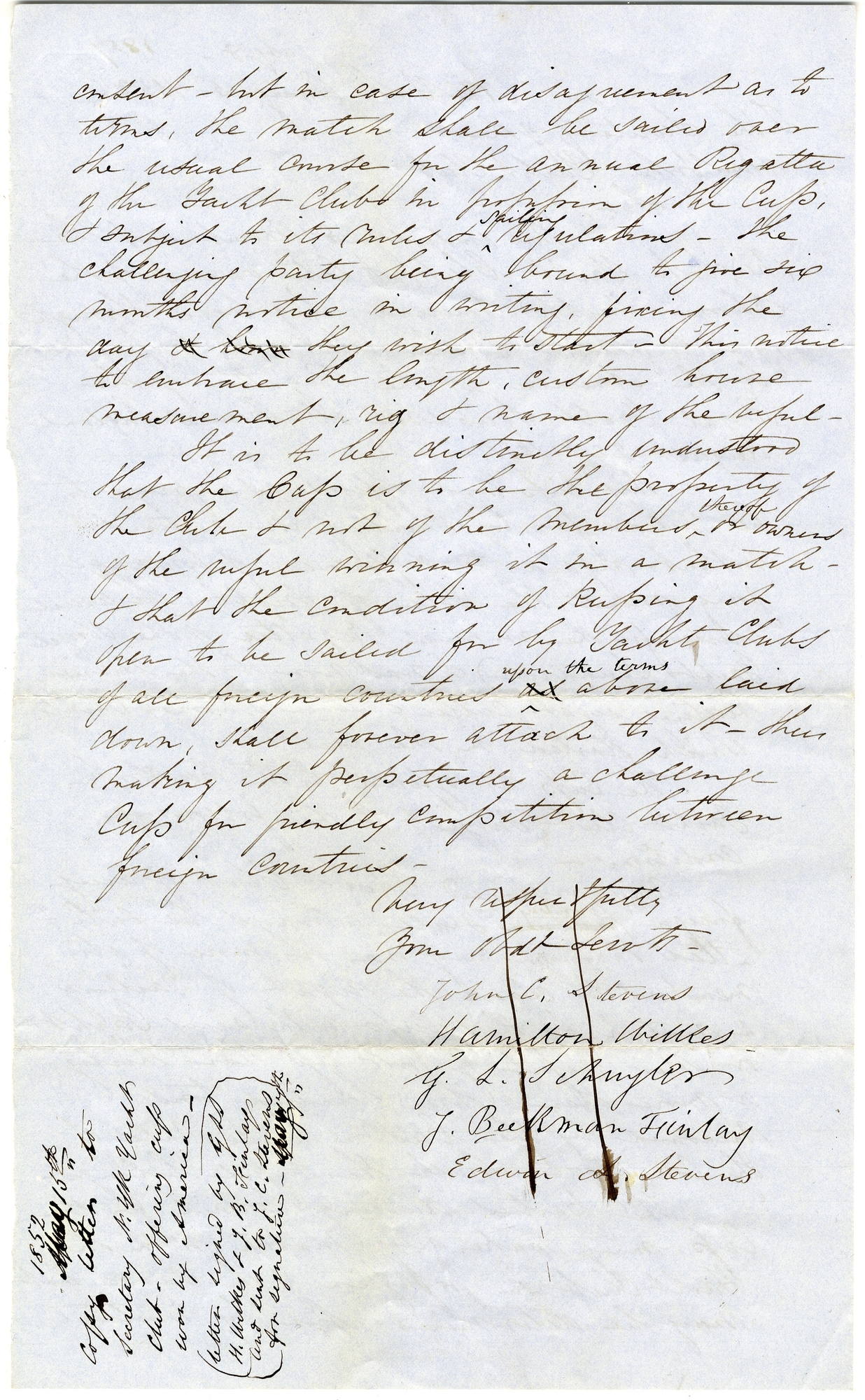

As the dust settled on the 1881 challenge, the question of returning the America’s Cup to George L. Shuyler for reconveyance arose and by resolution on 17th December 1881, it was indeed returned by the NYYC. As the remaining surviving member of the original America syndicate, Shuyler’s words were viewed as final and on the 4th January 1882 it was duly reconveyed to the club by a letter of gift, in which the Cup was vested in the club as a trustee with key conditions stipulated. Fearful as they were of the Canadians building yachts and towing them via canal or atop a steamboat, the stipulation that ‘vessels intending to compete for this Cup must proceed under sail on their own bottoms to the port where the contest is to take place,’ was inserted.

So too was a crucial paragraph around ‘mutual consent’ that stated: ‘The parties intending to sail for the Cup may, by mutual consent, make any agreement satisfactory to both as to the date, course, time allowance, number of trials, rules, and sailing regulations, and any and all conditions of the match…’

Shuyler himself was a patriot and also recognised the feeling among New Yorkers, and perhaps even wider across the States, of how deeply the America’s Cup was ingraining into the sporting landscape. The inclusion of wording that clarified that the Cup belonged to the club that held the trophy was set out more fully than was stated in the original deed to emphasise that the Cup was the trophy of the nation, and that should the club holding it at any time be dissolved, then the stewardship should devolve upon some other club.

With the Cup reconveyed and the new Deed of Gift communicated to clubs of significance around the world, it was perhaps surprising that no challenge came for almost three years after the writing of the deed in 1882. Yacht design too was evolving and with the English keeping a watching brief on Cup proceedings, it was decided that the days of the schooner were over and that the best chance to win the Cup was in the new breed of Cutters.

On February 26th, 1885, a challenge was sent by Mr Beavor Webb acting on behalf of the Royal Yacht Squadron, and Lieutenant William Henn of the Royal Northern Yacht Club for a double challenge for the America’s Cup.

And here continues one of the longest winning streaks in international sports.

CONTINUE WITH WHAT HAPPENED IN 1887: THE SCOTTISH CHALLENGE AND THE 1887 DEED OF GIFT