CONSTELLATION OF STARS

Following the Australian defeat in 1962 by the brilliance of Bus Mosbacher and his crew aboard Weatherly, the Royal Thames Yacht Club was quick to capitalise on its preferred status to challenge. With various individuals mooting interest in building boats and forming syndicates, the Club took a curious approach in getting the then Commodore of the RTYC, Admiral of the Fleet Earl Mountbatten of Burma, to issue a formal challenge to the New York Yacht Club in October 1962 requesting racing to commence the following year in 1963. This wasn’t met with approval, being rejected completely out of hand, as the American club required at least a full year’s breathing space before considering a challenge but a follow up document from the Royal Thames Yacht Club, challenging in 1964, was accepted immediately.

With the 12-Metre scene gaining popularity on the East Coast of the United States and the confirmation of Olin Stephens as the designer of the era, plus the perceived drubbing of the Australians in 1962, the New York Yacht Club quite rightly adopted a confident stance in its approach to the British challenge of 1964. Two notable defence parties emerged to build new boats and the most significant was the Walter S. Gubelmann and Eric Ridder, Constellation Syndicate backed by the new Commodore of the NYYC, George T. Bowdoin alongside a list of luminaries from the J-Class era including Harold S. Vanderbilt, the three-time defender, and Briggs Cunningham of Columbia fame in 1958.

Gubelmann was a Newport stalwart, a millionaire through the inheritance of the family business – the Realty & Industrial Corporation – and a leading light of the Newport Croquet Club as well as being a Republican donor and fundraiser. Eric Ridder was most known for his success in the 6 Metre Class where he was part of the gold medal winning team at the 1952 Olympic Games in Helsinki. Less well documented was his success in business, transforming the family print business, most notably with the Commodity News Service, into the international financial data company Knight Ridder. Gubelmann and Ridder would leave no stone unturned to produce the fastest 12-Metre of the era.

With Olin Stephens duly appointed as Chief Designer for the Constellation Syndicate, they immediately set to tank testing at the Stevens Institute in Hoboken. Meanwhile the NYYC, in a pique of competitiveness, sought to tighten up the rules regarding where components, hulls and hardware could be designed and manufactured, issuing a memorandum that precluded ideation or manufacture in the defending country.

With America leading the way in yacht technology, although it was of little argument at the time that Britain very much led the way in aviation technology, the move was met with much consternation. David Boyd, the English yacht designer who had been commissioned by Tony Boyden for a flagged RTYC challenger to undertake tank testing of a series of Arthur Robb models at the Stevens Institute before the memorandum was issued, was concerned that his work would be in vain, but this was later clarified, and the memorandum was deemed not to be retroactive.

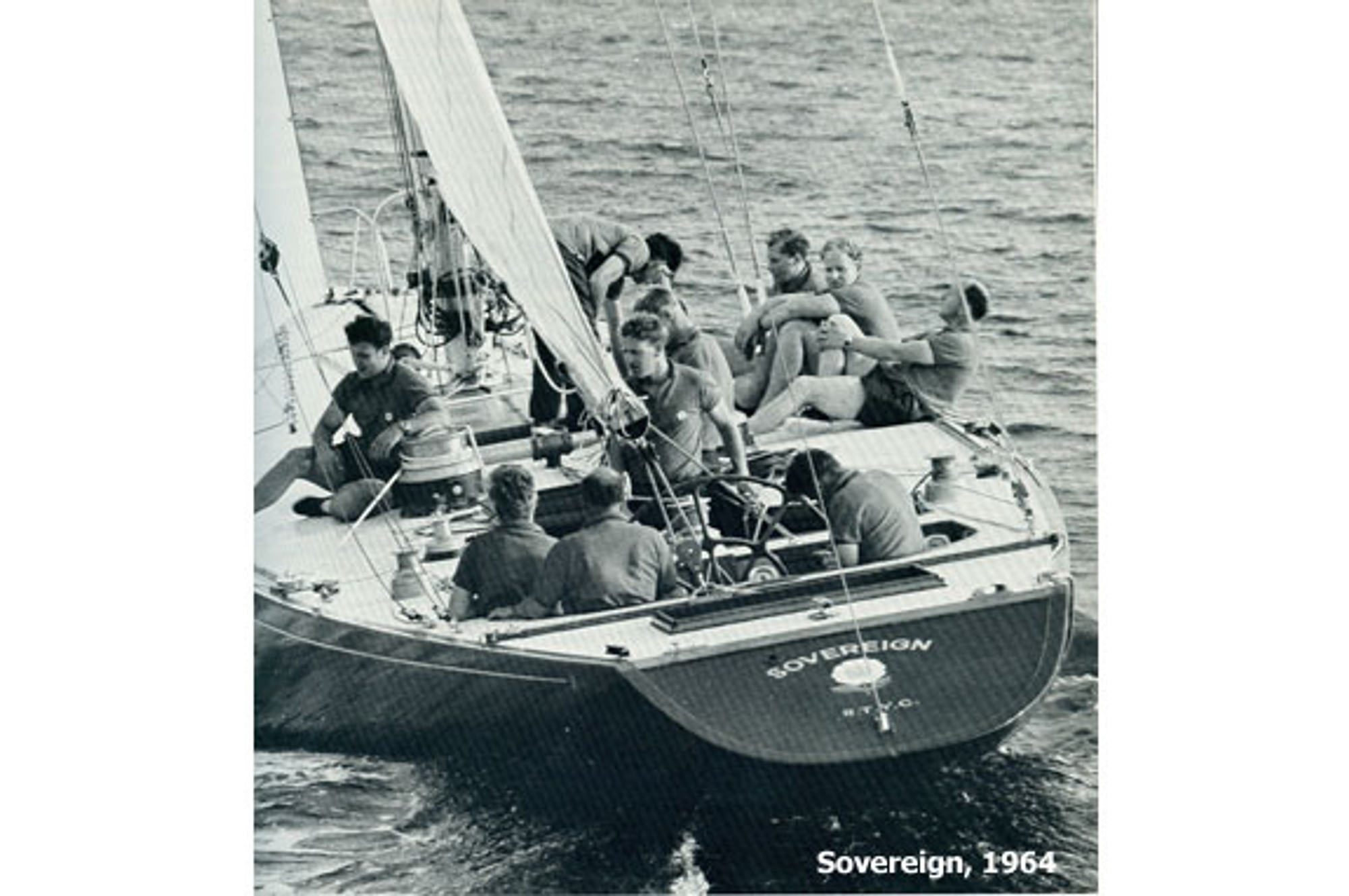

Tony Boyden’s syndicate on behalf of the Royal Thames Yacht Club was an attempt to put up a better showing than Sceptre had displayed in 1958 and restore some pride in British competitive yachting at the elite level. The yacht that was built at the Alexander Robertson yard in Argyll, Scotland was ‘Sovereign’ to the final design of David Boyd who had done away with some of the experimental features of Sceptre’s hull but, in execution, was sorely lacking in refinement, particularly in the rig, sails, and hardware. Furthermore, the campaign was characterised by a happy amateurism under a veil of professionalism with Boyden installing rugby players in the power positions placing much store in physical fitness over technical development and still very much assuming the English gentleman’s approach to yachting being a summer sport.

Sovereign was launched on July 6th, 1963, and immediately went into trials against Sceptre, coming out the stronger boat after some early scares and losses and learning quickly that smaller spinnakers equalled better manoeuvrability. Momentum was carried through to that year’s Cowes Week and a win over Olin & Rod Stephens aboard the aged Flica II gave the British some comfort that the boat could perform. Sovereign went for more trials in Weymouth just after Cowes Week before coming back to the Solent in late August 1963 where she promptly broke her mast and was then laid up for the winter.

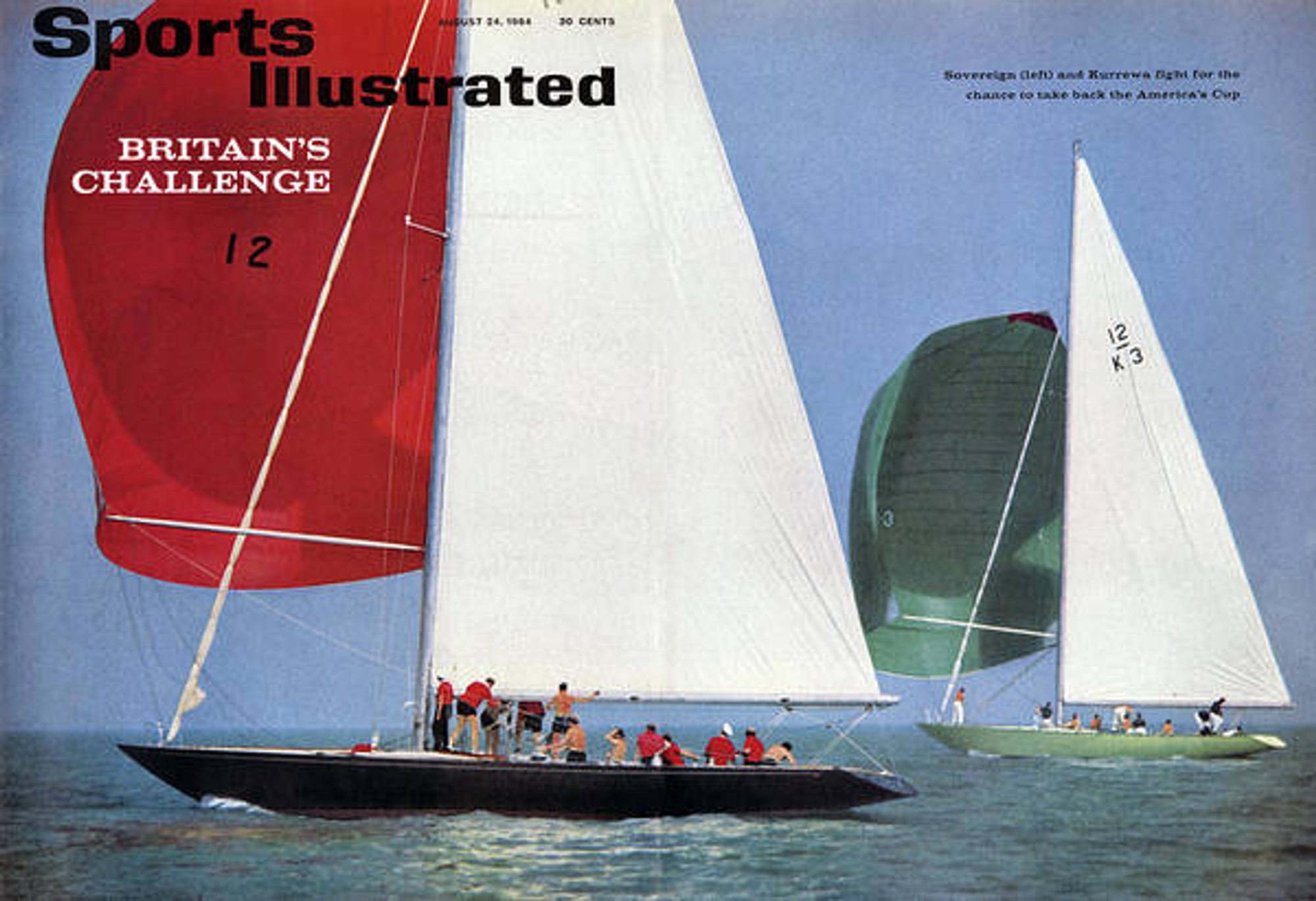

Sovereign was to meet stiffer challenge the following year after the launch of a new 12-Metre in 1964, Kurrewa V, owned by Australian brothers Frank and John Livingstone who had also commissioned David Boyd for the design and installed Olympic Silver medallist in the 5.5 Metre Class Colonel ‘Stug’ Perry on the helm. The imposing figure of Major General Ralph Farrant came aboard as navigator and tactician, but crew tensions led to the afterguard being nicknamed the ‘Officer’s Mess’ and the derogatory nickname of ‘mizzen mast’ given to Ferrant. In contrast, Sovereign’s crew came together with the appointment of the quiet and mannered Peter Scott as skipper with sailmaker Bruce Banks supporting the helm, the technical genius Dan Bradby as navigator and Sceptre-owner Eric Maxwell as crew boss in the afterguard.

When Kurrewa V and Sovereign lined up for selector trials through late August and early September 1964, it was Sovereign that triumphed but more by crew cohesion and good sailing from Scott than any speed advantage inherent in the design. Indeed, it was widely believed that Kurrawa V was the faster boat but poor sails, particularly downwind, callous tactics and a dis-jointed crew let her down. Sovereign was selected by a unanimous verdict and packed for shipping to Newport where the British worked tirelessly under the command of Peter Scott to find better speed. Instrumentation was a real focus with Dan Bradby as its chief proponent. The introduction of accurate speedometers was something of a revelation in 1964 even after some technical hitches with the displays being too close to the compasses, knocking them off their bearings. Much hope was installed in this challenge, but they faced down a team that had been through the wringer all summer and was more than match fit.

Aside from the Constellation Syndicate, another serious contender emerged in America to challenge for the defender slot in 1964. Pierre Samuel ‘Pete’ DuPont IV, a member of the wealthy DuPont family, bankrolled what was to become the American Eagle syndicate and hired Bill Luders to draw the lines of one of the most powerful 12-Metres seen to date. It was an all-star cast in the crew with Bill Cox as skipper alongside the likes of Halsey Herreshoff, George Hinman Jr., and George Isdale in the crew. American Eagle was a sensation almost straight after launch, but as was customary, the NYYC hosted no less than five 12-Metres to undergo a thorough selection series that summer to decide on the defender. Ted Hood returned with a re-vamped Nefertiti; the persistent Chandler Hovey came back for a third attempt with Easterner; whilst a Californian syndicate headed by Pat Dougan brought Columbia out of retirement for the series. Newport was alive with speculation about who would triumph, but American Eagle was the stand-out contender with the experienced Bill Cox on the helm whilst Constellation was seen very much as a ‘work-in-progress’ under the helm of Eric Ridder with Bob Bavier supporting in the afterguard.

The early trials were a tough experience for Constellation who succumbed to some notable defeats and scored some unconvincing victories. The team trialled a new two-ply mainsail, the results of which were inconclusive, even in stronger breezes where the thinking was that this would be a game-changer. Disagreements filtered into the afterguard over sail selection, and this translated into poor, unconfident decision making on the water for Ridder. Losses to both Columbia and Nefertiti were real setbacks for the sailors aboard Constellation, meanwhile American Eagle was beating all-comers at a canter.

The official defence trials begun on the 8th of July 1964, and with Newport wags nicknaming American Eagle, ‘the bird’, it was Bill Cox’s to lose. Constellation was showing some signs of improvement, but poor starting was hampering their efforts. American Eagle scored an early win over Columbia whilst Constellation posted a record margin of 14 minutes 51 seconds over Easterner, a convincing win over Nefertiti and a thumping eight-minute victory over Columbia.

All was set for a thrilling match between American Eagle and Constellation, the ‘bird’ still being unbeaten, and it was a close run affair – far closer than before – but a poor start by Ridder again put the team on the back-foot. Some gear failure on American Eagle on the run to the finish almost saw Constellation through, but some determined crew-work saved the day and American Eagle won by 54 seconds. The series, for Constellation, continued in the same vein with poor starts against Nefertiti and Easterner with the ultimate humiliation of grazing the Committee Boat in one start and Ridder, a laconic but deeply intelligent man, looked inwards to himself and knew the game was up, proclaiming to co-skipper Bob Bavier on a desperate run against Nefertiti: “Tomorrow you start.”

This was the turning point for Constellation. Time magazine later recorded that: “It takes a big man to remain in the background while another man steers his dream," allegedly said by a crew member, but Ridder wanted the America’s Cup more than the dream.

Bavier's great skill was in getting the last fraction of a knot out of his sails and hull. He was not a man for complex tactics, and in the racing against American Eagle, rather than forcing Constellation around the course or into tactical situations, he left most of the manoeuvring to Bill Cox, preferring to concentrate on building dynamite boatspeed.

In the final race of the opening trials before the annual New York Yacht Club cruise regatta, Constellation was a different boat, leading handsomely against American Eagle before thick fog curtailed the race. A set-back then occurred whilst sailing in the cruise regatta in 25 knots with Constellation losing her mast due to an under-spec’d titanium clevis pin – American Eagle went on to win again. The mast was replaced quickly on Constellation with an aluminium one and when the two boats met again it was to be the first time that ‘the bird’ lost that summer. As the cruise regatta progressed, Constellation simply got better and better, winning what were effectively two-boat match races between her and American Eagle as the two stretched ahead of the other 12-Metres, with increasingly larger margins. All was set for the final selection series for the defender nomination that begun on August 17th 1964.

Very quickly the services of Columbia and Nefertiti were excused by the NYYC after some considerable losses to the newer, faster boats and the scene was set for the deciding seven race series between the two stand-out performers of the summer. Constellation had truly arrived as a contender not just for the defence slot but for the America’s Cup itself and Bob Bavier, still with Eric Ridder in the afterguard, proved that he had what it took to handle the white-hot intensity that American Eagle’s Bill Cox threw at the contest.

The early conditions in the trials certainly helped Constellation, of that there is little doubt, with the light to moderate airs suiting both the refined sail-plan and rig of the Olin Stephens design. American Eagle was a fuller-bodied boat, and it was believed to be better in the upper ranges but in the fifth race of the series with Constellation up 4-0 and still no word from the committee about selection, the two came together to settle the score in a 14-knot building breeze. Constellation more than met the challenge and recorded a resounding 2 minutes and 5 second victory. A final race was held where the positions were turned inside out by a 90-degree windshift but the NYYC Committee had seen enough and Henry Morgan duly boarded Constellation to say: “Mr Ridder, I have the honour to inform you that Constellation has been chosen to defend the America’s Cup.”

The 19th Match for the America’s Cup was greeted with much enthusiasm in Newport as some 40,000 spectators descended on the town and out on to the water to see the opening exchanges. The American yachting public were certain that Constellation would win and see off yet another poor British challenge but the pre-start in the first race on the 16th September 1964 showed that Peter Scott and his crew on Sovereign had fight in them albeit with a boatspeed deficit that made them fight with effectively one hand tied behind their back.

In a building 8-10 knots (that would later rise to 16 knots) Bob Bavier held control as the chaser before breaking away in an attempt to get the weather position up by the committee boat. The Sovereign afterguard did their best to cover the move but were slow in execution, leaving the British boat slower in the water and allowing the Americans to hit the line with pace and power to windward. It was a masterclass in starting from Bavier and over the first upwind leg they looked far the more settled boat with the crew almost invisible and staying either low in the cockpit or hiked lying over the side.

At the top mark the Americans were almost two minutes ahead and over the next four legs just simply pulled away, making better through the chop and thoroughly outclassing Sovereign. The finish saw a victory by 5 minutes and 34 seconds to Constellation and the writing was on the wall for the British.

If race one had been considered a disaster, race two was an embarrassment. Starting to leeward and behind, Constellation looked for all the world to be on the back foot but the superior pointing ability and far better profile through the lumpy seas, saw the Americans agonisingly grind up to windward, through any lee cast by Sovereign and within a few minutes forced the British off. It was a power display and totally disheartening for Peter Scott and his crew. By the top mark, after Bavier had kept what can only be described as a loose cover, Constellation was leading by 3 minutes 43 seconds.

Over the next four legs, Constellation just pulled ahead and with some crazy roll-of-the-dice tactics from Scott not paying off downwind and a fateful adverse windshift, the final finishing delta was a thumping 20 minutes and 24 seconds. Rumour abounded dockside on the lay-day called by the British that Scott would be replaced, but this was angrily denied by the Royal Thames Yacht Club.

Peter Scott was indeed installed on the helm of Sovereign as the boats came together for race three in a brisk 20-knot easterly and confused seaway. The Americans, with their tails up, completely fluffed the start, crossing the line five lengths adrift of Sovereign and in considerable dirty air. There was simply no panic onboard Constellation as her reduced pitch and power was relentless through the chop and within half a leg she had seized the lead. There was little the British crew could do and as Bavier described later: “I have never felt Constellation so alive, so much in the groove.” Once the lead had been established at the top windward mark, the next four legs were a lesson in conservatism and big game closing out of the regatta, with Constellation extending slightly and recording a 6 minute 33 second victory. 3-0 and Match point to the Americans.

However, the conservative sailing of race three was something that didn’t sit well with the yachting establishment in America. One journalist remarked that: “It doesn’t matter how lousy a start Bavier gets, that bloody boat bails him out.” And those words stung the American skipper into action in what would prove to be the final race as he adopted for all-out aggression in the pre-start.

For a full eight minutes, under mainsail alone, the Americans sat on the British boat’s stern as the two circled and led away. Then, in the final approach to the line with two minutes left on the countdown, Sovereign were desperate to break the leeward position they found themselves in and broke out their overlapping genoa early. It was a fateful mistake that whilst propelling them forward, put them over the line early and effectively ended the contest as they had to return, whilst the Constellation sailed away. In the swell which had replaced the chop of the day before, the Americans were a class apart. At the top mark they led by just under five minutes, by the finish, and after stretching out on every leg, they took the winners gun and retained the America’s Cup with a convincing margin of 15 minutes and 40 seconds. It was what the New York Herald-Tribune called: “Murder on the High Seas.”

That the Sovereign campaign lacked in ambition, was not in doubt, it was also at a serious technical deficiency in nearly all areas of the boat, rig and sails and the inherent boatspeed of Constellation across a range of conditions in the Match made the contest of 1964 a completely one-sided affair. Blame was laid at the door of Sovereign’s designer David Boyd but some of the severest criticism came from the American yachting writers who criticised the mentality of the British, with John Young, writing in The Times of London, stating pointedly: “It is pointless mouthing platitudes about gallant losers and a great-hearted attempt to capture the prize. There is nothing chauvinistic in claiming that this has been a stunning disgrace.”

Unbeknown then, the Sovereign campaign was the last time a British yacht would contest the Match for the America’s Cup – a record that stands to the day this precis was written (2022). The Australians wasted little time in capitalising on the British malaise, with Sir Frank Packer’s team handing an envelope containing a challenge to John C. Stillman, Commodore of the New York Yacht Club, for racing in 1967 on behalf of the Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron.

And just as the candle on British involvement was well and truly snuffed out, the thunder from down under was growing.