THE CUP THAT CHANGED EVERYTHING

The considerable advantage that the New York Yacht Club had exerted on the Cup since it first defended with a fleet of yachts on home waters in New York against the railway heir James Ashbury in 1870 was, by the 1960’s, beginning to erode. A memorandum in 1962 had declared that if multiple challenges were received within 30 days of a successful defence that they would be ‘received simultaneously.’ The fact that the Australians and British came to a gentleman’s agreement in 1964 precluded multiple challengers from entering that year and in 1967, despite a non-starting entry from the French, two rather mis-matched Australian boats vied for the challenger slot and only one, Dame Pattie, arrived in Newport.

Furthermore, the NYYC, so long the iron-fisted holder of the Cup and writer of the rules, adopted a stance via a memorandum on January 19th 1970 that many commentators believe signed the America’s Cup to an inevitable destination – away from the New York Yacht Club. The memorandum clarified the protocol going forward and paved the way for multiple challenges to be accepted. And in 1970, the Cup world was all about to change with the emergence of one of the most colourful men in America’s Cup history – the French manufacturing tycoon Baron Marcel Bich – who kick-started the French involvement in the America’s Cup.

As soon as the 1967 regatta was concluded with the successful defence by Intrepid, no less than four challenges were received by the New York Yacht Club. Australia would be back with a renewed Sir Frank Packer campaign, meanwhile Great Britain and Greece tentatively threw their hat in the ring. But the real eye-catcher was the French who had sat out the 1967 event due to a perceived lack of experience but were busy buying up the 12 Meters (Kurrewa V, Constellation and Sovereign), commissioning Britton Chance for a side-project and setting up camp in Hyeres.

Baron Bic spent a reported $4m, a simply huge sum in 1970, with a commitment to bridging the experience gap to the Americans, Australians and British. He hired in Eric Tabarly, the undoubted star of French sailing whilst also bringing in 5.5 Meter Champion Louis Noverraz, 505 champion Jean-Marie le Guillou and Poppy Delfour one of the country’s top skippers. In Britton Chance he commissioned the American on a one-off basis to build an out-of-class 12 Meter called ‘Chanceggar’ in order to give appointed naval architect André Mauric, the son of a Marsellais cabinetmaker who had designed the fastest Starboat in the world at the time, a baseline of data from a modern 12 Meter. It was money-no-object, as well as being an almost party-scene in Newport with the enigmatic Baron setting up house at one of the grandest mansions on Bellevue Avenue, but acted as a huge boost to France’s participation in the America’s Cup.

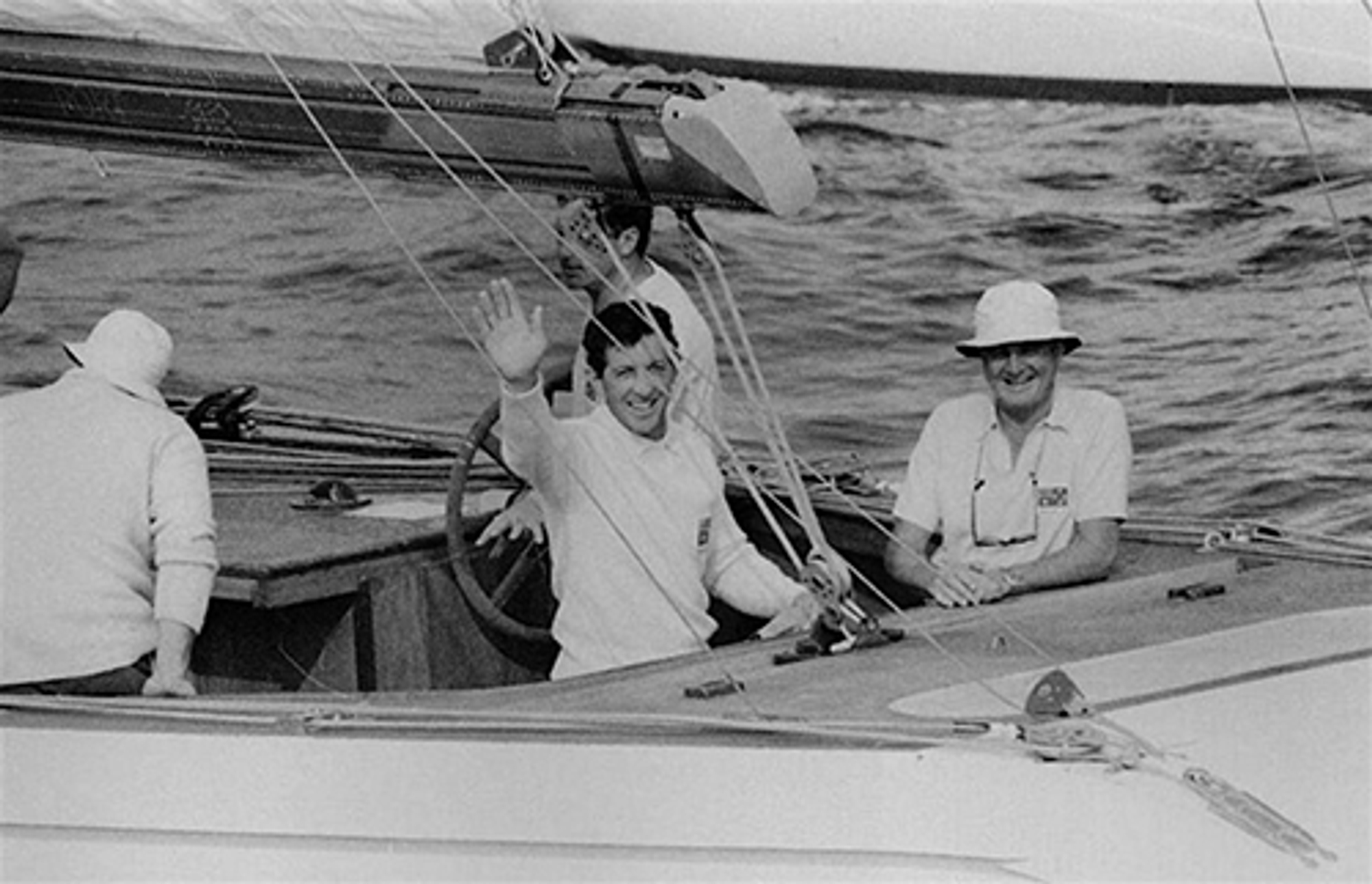

Whilst the French were getting immersed in their first campaign, the Australians under Sir Frank Packer had re-grouped and appointed Alan Payne as chief designer. Payne’s long experience by now in the Cup led him down an ever-more scientific path. Tank testing at Sydney University was now a far more technical approach with tools developed under the watchful eye of Payne whilst the introduction of wind tunnel testing on the rig produced some major advances that made the Americans, most notably Olin Stephens, sit up and take notice. Perhaps one of the biggest advances was discovered by Professor Peter Joubert, Payne’s good friend, who spent a day sailing with skipper Jim Hardy and realised that the greatest struggle for a skipper of a 12 Meter was visibility and being able to see both the genoa and the waves. This led to the implementation of the twin wheels that became ubiquitous on 12 Meters thereafter and was notably a feature on the American defender also in 1970. Gretel II as she was named, was everything that the original and much-modified Gretel was not. In the hands of Jim Hardy, this was an Australian challenge that had all the hallmarks of being one of the strongest challengers in Cup history.

The French, however, were the first hurdle for Gretel II to overcome. Baron Bich’s syndicate built their 12 Meter across the border from the Egger Boatyard in Lake Neuchatel in order to meet the strict build nationality restrictions of the Cup, with French labour to Meuric’s lines but at launch, ‘France’ as she was named attracted derisory comments from the American, Britton Chance, who said: “France is a copy of my boat (referring to ‘Chanceggar’ that he had designed privately for Bich) with mistakes; the only changes they made are wrong.”

In the early challenger trials though, France looked a match for Gretel II, and with Louis Noverraz on the helm in a thrilling opening race, led all the way around only to fall into a wind hole on the last leg. Inexplicably, Bich replaced Noverraz on a whim and installed Poppy Delfour for race two which was held in desperately light airs that would have suited Noverraz perfectly being that he had grown-up sailing on the Swiss lakes.

Delfour lost the start and was some 200 yards astern at the top mark but in the fluky conditions, aced the run to the leeward mark and the French were leading before again being overtaken upwind leg. But in a repeat of the first lap, on the final downwind, as the wind shut down completely, Delfour managed to get France ahead again before a shrewd sail change from spinnaker to ultra-light genoa on Gretel II pulled her away, ghost-like, into an unassailable lead. True to form, Delfour was replaced on the spot by Bich in favour of Novarraz, adding to the chaotic shoreside presence that marked France’s first foray into the America’s Cup.

The change had little effect as the third race of the challenger series was held in heavy breeze that topped out at 29 knots and well out of the design range of France, affording the Australians who excelled as sailors in the breeze, a comfortable victory. But more drama was to come from the French following race three with the indomitable Bich sacking both of his helmsmen and then, dressed in a white double-breasted suit, white shirt, yacht club tie and white gloves replete with a white topped yachting cap, stylishly took the helm for the final race with Eric Tabarly beside him as navigator.

Quite why the gallant Baron chose to helm remains a source of speculation with some suggesting that he chose to grasp the story and take the blame of defeat (if there were to be any) and deflect criticism back home from his appointed skippers. Whatever the truth of the matter, Bich’s turn on the helm was somewhat of a ‘Catastrophe!’ as quoted in the French journal La Monde, with France getting lost circling in the Newport fog whilst Gretel II sailed the course and sealed the Challenger slot. France would be back and lessons of a haphazard but ultimately fun campaign that is burnished in the memory of all who witnessed it, were hard learnt.

The New York Yacht Club meanwhile had high hopes pinned on its superstar designer Olin Stephens for a new yacht, ‘Valiant’, that was built to the order of vice commodore Robert McCullough. Britton Chance meanwhile was hired by William Strawbridge to update the all-conquering Intrepid from 1967 and both designers went to work tank-testing at the Stevens Institute in Hoboken. With so much confidence in Stephens, the expectation around Valiant was for another rocket-ship that would move the dial on yacht design once again.

Unfortunately, those hopes were mis-placed. Valiant was a difficult boat to steer and her trail wash was considerable. Stephens later lamented that the small-scale test runs in the tank threw up inconsistent data and highlighted, amongst other things, the design conclusions of the small-scale modelling that led to Charles Morgan’s beautifully adapted but ultimately slow ‘Heritage’ – one of the prettiest 12 Meters ever built. Chance however, had put together a programme with Bill Ficker as helmsman of Intrepid that was un-relentingly precise in its execution with every detail and every modification carefully considered, noted and assessed.

The American trials were a four-way affair with Valiant, Intrepid and Heritage joined by the much-upgraded Weatherly of 1958 with George Hinman on the wheel. In early trials, Valiant and Intrepid shared wins but easily dispatched Heritage. By the end of the first series Valiant was 5-3 up against Intrepid but the New York Yacht Club harboured grave doubts about Valiant’s straight-line speed and headed into the observation trials in July 1970 eyeing the possibility that Intrepid could be, once again, the yacht to defend the America’s Cup.

The NYYC Cruise regatta did little to enhance Valiant’s case after a race where she struggled to beat Heritage and a further race against Intrepid that saw her unable to point anywhere near as high off the line and suffered through manoeuvres. Immediately after the Annual Cruise, all the boats were sent for upgrades – some more dramatic than others with Heritage undergoing reconstructive surgery on her mast, keel and rudder whilst Weatherly tacked on a new mainsail. Intrepid, under the design of Britton Chance, opted to upgrade with wide fairing strips that led from the maximum beam mark all the way back to the rudder to lengthen the waterline.

When racing recommenced, it was what proved to be, a false dawn for Valiant who won the first race by a margin of 42 seconds against Intrepid and then went on to win races against Weatherly and Heritage. Intrepid dispatched the elder boats too in quick succession and it came down to a straight fight between Intrepid and Valiant for the defence slot. Bill Ficker aced the next six races, steering Intrepid to wins of greater and greater margins supported by an afterguard consisting of Steve Van Dyck as tactician and Peter Wilson as navigator who gelled in a variety of conditions and left the New York Yacht Club with no other choice. The 1970 America’s Cup Match would be Intrepid versus the hard-charging Gretel II and Newport was alive to the contest.

The racing certainly didn’t disappoint. Right from the first starting gun, the now established match-racing tactics of circling and trailing were much in evidence. Jim Hardy was fired up for the contest and the first protest flag of the series flew as the two boats bore away on opposite tacks in close quarter. Hardy seized the initiative and trailed hard on the stern of Intrepid and with 30 seconds to go, tacked off on a mis-timed run into the line. Bill Ficker held course on a perfect line and at the gun, Intrepid was at full speed.

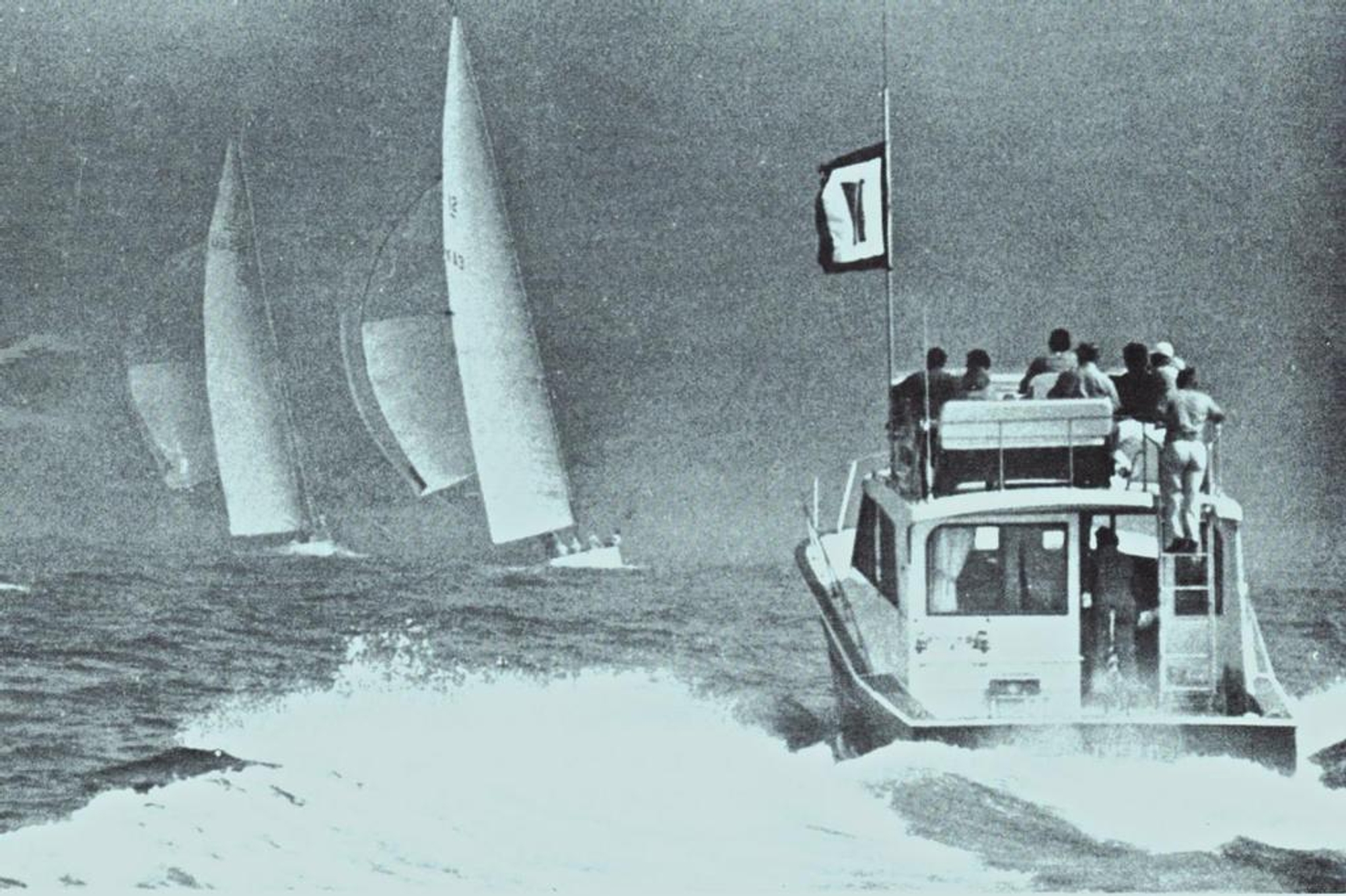

It was a lead that she would never relinquish despite the race turning into something of a farce as it proceeded. First, Gretel II wrapped her kite around the forestay before snapping her spinnaker pole on the first hoist before being almost swamped by the wake of the spectator fleet following Intrepid. As the wash trundled down the deck, it flushed oil from the winches and in a dramatic moment, Paul Salmon the foredeck boss, was washed overboard meaning a return to collect him. It took two attempts to get him back onboard. Further calamity struck the Australians on the final leg as a US Destroyer and a Coast Guard crossed her path before the spectator fleet broke the imaginary boundary and entered the racecourse, causing the chop to increase severely. Gretel II finished the race some 5 minutes and 52 seconds astern of Intrepid with both syndicates complaining colourfully to the NYYC Committee Chairman Dev Barker. The Coast Guard was called in for a meeting and promised to do better. They held true to their word for the rest of the series.

Shoreside though, a number of protests were heard relating to the pre-start hunting that Jim Hardy had inflicted on Bill Ficker with many observers believing that the Australians had a very strong case being on starboard and with rights. However, the protest committee were having none of it and as Jim Hardy said afterwards: “We left the protest meeting like little boys who have just been lectured by their schoolmaster.” Two protests were summarily dismissed. The score was 1-0 to Intrepid.

Immediately after the race, Hardy called a meeting with an idea to install Martin Visser as the starting helmsman due to the fact that he had shown more aggressive tactics at close quarters in trial races. Sir Frank Packer and skipper Bill Fesq agreed, and Hardy would resume the helm position once clear of the line. It was a shrewd move by Hardy and in the second race, Visser stuck Gretel II expertly ahead and to leeward on the line in a classic match-race start that caused Intrepid to quickly tack away.

By the top mark, the Australians were in a commanding lead of almost two minutes but after two poor reaching legs found themselves astern at the leeward mark as mild fog crept across the racecourse. Now came a bizarre call from the NYYC Committee that was, it was later found, based on suspicion of outside assistance being accepted by the Australians. The Americans had noted several races in the challenger selection series against France where Gretel II seemed to uncannily be able to position themselves perfectly around the racecourse in fog and suspected that they were receiving course plots externally. The truth is that Bill Fesq had innovatively installed a doubled electronic system, set at right angles, from the UK nautical electronics firm Brookes & Gatehouse that gave an accurate dead-reckoning position, but the suspicion was intense amongst the Americans and the race was dramatically abandoned on the second upwind leg and the suspicions raged for years, decades even, afterwards.

With an increasingly fraught backdrop enveloping the regatta of 1970, the re-run race two was to see a further souring of relations between the Australians and the Americans, centred around a pre-start foul that took aerial photographic evidence to eventually decide. However even before the starting sequence had begun, drama occurred on Intrepid as Steve Van Dyck, the American navigator was bitten by a ‘Yellow Jacket’ wasp and suffered a severe reaction so bad that he had to be taken to a tender and then airlifted by the US Coast Guard to hospital.

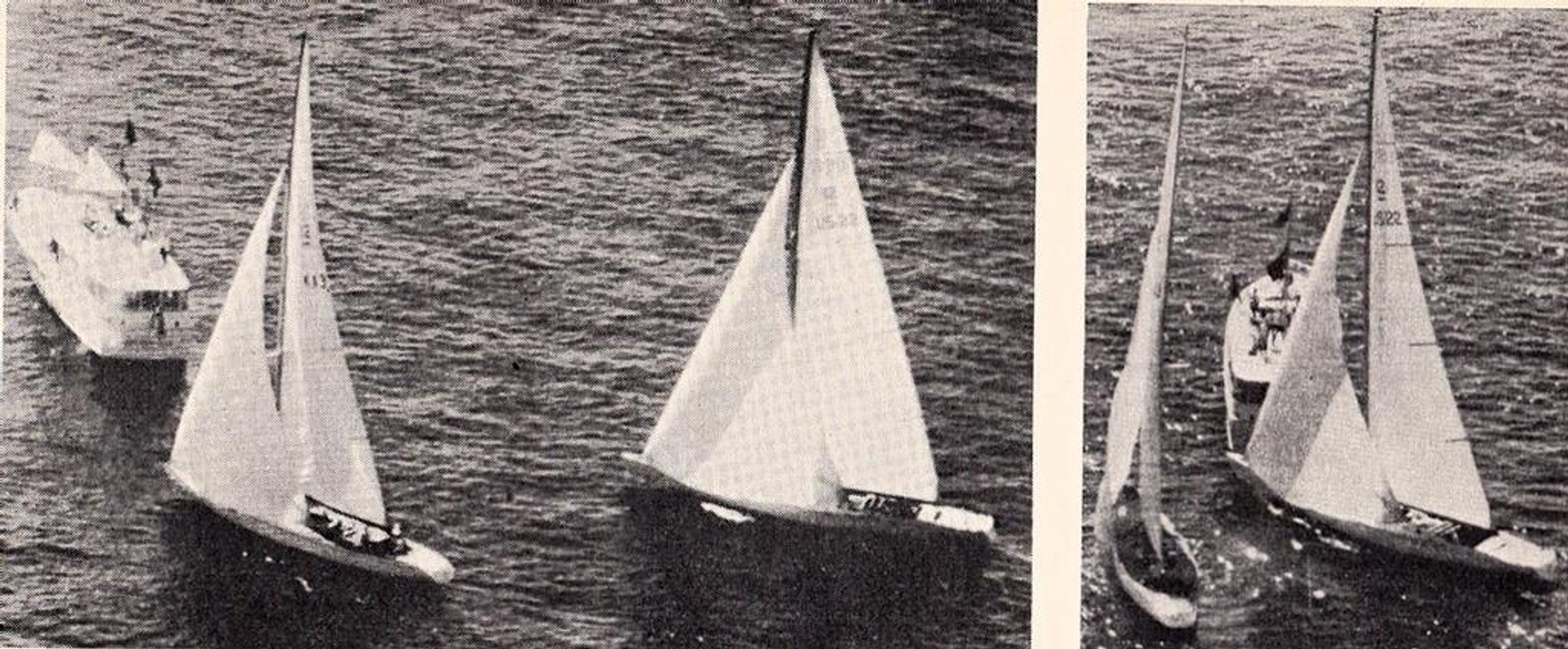

With the crew drama resolved, in light airs, and after considerable circling, both boats were coming in on the approaches to the start-line with Gretel II set up for a committee boat start and Intrepid seemingly trapped to windward. In the final seconds, Gretel II sought to shut out the Americans aggressively. However, the timing of Visser was arguably slightly adrift and in the desperately light airs, he struggled to get Gretel II’s momentum through the water enough to make the block. Bill Ficker, Intrepid’s helm spotted the gap emerging before him and with more speed effectively barged in at the committee boat only for Gretel II to respond with a slow luff that saw the two boats come together with the Australian bow glancing Intrepid just behind the shroud plate a few seconds after the starting gun had fired.

What followed was a fascinating light air duel whilst both boats carried protest flags. A 24-tack tacking duel ensued up the first windward leg with Intrepid emerging ahead at the top mark but good sailing downwind by David Forbes who assumed the helm for the offwind legs from Jim Hardy saw the gap close. On the next windward leg, with Hardy back on the helm, Gretel II closed again before handing back to Forbes to work his magic downwind. With a smaller spinnaker set perfectly, Gretel II passed Intrepid and led at the final leeward mark by over 100 yards. Hardy brought Gretel II home after a short tacking duel to score what looked like a fabulous win by 1 minute and 7 seconds, but the race was set to be decided in the protest room.

For all the world, the Australians felt that they had every chance of success in the protest room and still to this day, many of the famous sailors who graced that campaign – including John Bertrand who was the jib trimmer of Gretel II and who went on to win the America’s Cup in 1983 – felt that Intrepid had barged in and had no rights. The protest committee however, received first a detailed explanation from Bill Ficker, an architect by profession, who presented not only precise prose outlining the American viewpoint but explicit and detailed drawings of the situation. Ficker’s presentation was ultimately amplified by the emergence of photographic evidence in the form of a series of stills that even showed the smoke emanating from the starting canon and the protest committee’s decision was swayed.

In effect what it boiled down to was an interpretation of when Gretel II was obliged to give room to Intrepid. Ficker argued that Rule 42.1 (e) of “not sailing past close-hauled after the starting gun and before the line,” had been violated by the Australians and after much deliberation, and with all the evidence presented, the committee agreed. It was 2-0 to the Americans and Sir Frank Packer was incandescent, calling for an immediate re-opening of the case and re-instatement of Gretel II’s win. It fell on deaf ears and a short response was issued by Devereux Barker III, Chairman of the Protest Committee, citing no new evidence being presented and therefore no reason to re-open the case.

The Australians remained furious at the decision but recognising that they not only had to win against a yacht but also against a hometown protest committee (despite the presence on the committee of a non NYYC member in Gregg Bemis), Jim Hardy re-assumed the helm for race three to quieten down the aggressive starting practices of Visser. It proved to be a mistake as Ficker seized the advantage in the pre-start and then pushed Gretel II over the line early. Whilst both boats were over, Intrepid was in a better position to duck away and come back onto the wind with even more speed. With Hardy having to duck right away, Intrepid was off to the races and in a choppy sea was never headed but never really extended. The final delta proved to be almost the time that the Australians had lost at the start – 1 minute and 18 seconds. It was 3-0 to the Americans and match point.

What race three had shown however, was that Gretel II was a match for Intrepid in anything under the mid-range conditions and the Australians, with an afterguard of stellar sailors, was a match for the Americans. Newport denizens and seasoned American commentators were still uncomfortable about the destiny of the America’s Cup and their worst fears were confirmed in race four.

On an atypical Newport day with the wind clocking and backing through a 15-degree arc, Bill Ficker took the decision to try and close out the regatta through a run-and-hide strategy, refusing to engage with the Australians and only mildly responding to a tacking duel once ahead. The American skippers’ tactic though was found out rather cruelly on the final leg, in a rapidly dying breeze, and with a lead of over a minute as a 90-degree shift filtered across the course, favouring the Australians who had spent the race closing the gap down to just 100 yards and who now seized the lead for a fraught final leg to the committee boat finish line. Despite rolling the dice with a clever positional move, the shift never came back for Intrepid, and the Americans were beaten by 1 minute and 2 seconds. It was Sir Frank Packer’s second clean victory in the America’s Cup and a cause for much celebration in Newport that night.

The repercussions though of the race two disqualification sat uneasily on Jim Hardy’s mind and following consultation with the likes of the designer Bruce Kirby and the established authority on yacht racing rules, Gerald Sambrooke-Sturgess in London, Hardy convinced Sir Frank Packer to try and re-open the case on appeal. It was shut down curtly by the New York Yacht Club once again and the boats emerged on the 28th September 1970 for what would prove to be a thrilling final race of the series.

Race five was held in a shifting, light northerly airflow, conditions well-suited to the Australian design of Alan Payne that was regarded as a faster boat in the lower ranges. Jim Hardy won the start convincingly and, with pace, quickly stretched into a commanding lead of some 200 yards. With no other option, Intrepid had to try and force an error and instigated a tacking duel with Bill Ficker in phase with the shifts to such a degree that he reeled the Australians back at an alarming pace. In the final approaches to the top mark, the Americans seized the lead, powering over the top of Gretel II as she attempted a lee-bow position to leeward and perfectly on the layline. It was the slam-dunk move that forced the Australians to put in a short two-tacks to get round the mark and handed Intrepid a 150-yard lead down the two reaches.

The second upwind leg was a thriller however, with a big windshift that briefly put the Australians ahead before abating and coming back to Intrepid. The gap had narrowed to just 100 yards by the second windward mark and was further narrowed down the final run with Gretel II closing to within 30 yards but as the boats came into the last leeward mark, a persistent windshift filtered across the Newport racecourse turning the beat to the finish into a fetch and Intrepid maintained station to record a 4-1 series victory.

Australia were left smarting about ‘what could have been’ and in Gretel II they knew that they had the boat to beat the Americans in typical Newport conditions. Intrepid was victorious due to its remarkable skipper in Bill Ficker, enhanced by a crew that was drilled to military standards, and supported by key decisions going their way.

From the outside it was an easy, and almost certainly false, suggestion to make that the New York Yacht Club was in some way biased but Sir Frank Packer left a memorable quote that stayed long after the 1970 series: “Protesting to the New York Yacht Club is like complaining to your mother-in-law about your wife.”