FREEMANTLE PUTS IT ON

The dust took a very long time to settle on the against-all-odds win by Australia II in 1983. A White House reception was hosted by President Ronald Reagan before the Americans finally relinquished a trophy that had been under the custodianship of the New York Yacht Club for 132 years. As Reagan’s magnanimous speech ended, he uttered the rousing words: “But I have one final piece of advice to the Royal Perth Yacht Club – don’t bolt that Cup down too tightly.”

Saturday 31st January 1987 dawned with high cloud cover and a shifting breeze more reminiscent of Newport, Rhode Island, than what the Challenger and Defender trials had delivered. A split-tack start saw Stars ‘n’ Stripes dial off for a perfect pin end time-on-distance run whilst Peter Gilmour stalled out at the Committee Boat end and the tale of the race was pretty much determined as a 20-degree windshift favoured the Americans, Conner wheeled over into it, forcing Iain Murray to tack beneath and behind, as both boats headed out to the far-right corner of the course. Kookaburra III got caught too far into the spectator fleet out right, Stars ‘n’ Stripes just avoided it and at the top mark Dennis Conner was leading by 1 minute and 15 seconds. With the run turning into a reach, the race became processional and more windshifts just failed to matter for the Australians who couldn’t get back in touch. Conner elected to keep it tight though, knowing that in those conditions, large deltas could be hazardous and just let his sublime team change up and down sails as the breeze went from 8 to 18 knots. The winning margin was 1 minute 41 seconds and Conner was on the charge.

The next day (Sunday 1st February 1987) saw more normal conditions return to Gage Roads with a building breeze that saw the boats starts in 21 knots and finish in 25 knots with a heavy swell that peaked at 5 feet, and it was all about the drag race off the starting line. In fact, Peter Gilmour had made an error, crossing the line early in the pre-start and being forced to gybe around the Committee Boat. Conner was early too and tacked onto port to go to the stern of the Committee Boat but realising the potential for a port/starboard incident, dialled away, gybed and came back to the start-line at full pace. Arguably it opened the door for Kookaburra III and let them back into the race, but Stars ‘n’ Stripes started with pace and eased into a slow-motion lead a quarter of the way up the beat, forcing Iain Murray now steering the Australian boat, to wheel away. Conner was 12 seconds ahead at the gybe-set windward mark and eased away to 29 seconds by the leeward mark before a remarkable upwind leg with the Americans showing better technique through the waves eked out a 1 minute 14 second lead which in the steady breeze they wouldn’t lose. A loose cover up the final beat in classic match-racing style gave another win to Stars ‘n’ Stripes by 1 minute and 10 seconds. 2-0 to Conner.

The old sailing adage that ‘a little bit of boatspeed makes you a tactical genius’ came to the fore in race three as a split end start saw Kookaburra III snatch an early lead up the first beat having started at the Committee Boat end of the line. Stars ‘n’ Stripes had taken the pin end hard but, on the tack back to engage, found themselves unable to cross and were forced into tacking beneath the Australians. When Kookaburra III chose to protect the right side of the course by tacking away and then coming back, again Conner was forced to tack to leeward, but the gauge was closing and by the third engagement, elected to take the transom of the Australians who had not quite got up to speed on a new starboard tack. The standard procedure is to cover immediately and perform the ‘slam-dunk’ manoeuvre, but it was a downspeed tack and Conner at full pace powered through the Australian’s lee. Game over as Conner now held the right and the starboard advantage as the two boats came in on the first windward mark and enjoyed a 15 second lead. It was the only time Conner was headed in the Match for the 26th America’s Cup.

A bear-away set away from the confused air of the spectator fleet lining the left-hand side of the course (looking downwind) took Stars ‘n’ Stripes into better breeze whilst Iain Murray called for a gybe-set and wallowed in confused air. It was all going Conner’s way and then a genius call by Tom Whidden up the second beat sealed the race. Noticing white-tops over to the right of the course (looking upwind), Whidden called for a disengagement from covering Kookaburra III and one of the greatest tacticians of all time, nailed it. Stars ‘n’ Stripes clicked into the new breeze first and rounded the windward mark some 1 minute and 21 seconds up ahead of the two reaches.

Stars ‘n’ Stripes held firm down to the leeward mark, but drama ensued on the final beat to the finish as the Kookaburra III Chase Boat came alongside and informed the Australians that a credible threat of a bomb onboard had been received. “What the bad news?” came the response from Iain Murray as crew members went below to check the hull from stem to stern. The Royal Perth Yacht Club Cup Committee had been prepared to abandon the race if Murray requested but sure in their team’s tight security, the Australians elected to sail on. They crossed the line 1 minute and 46 minutes behind the Americans and Dennis Conner was now one race away from a remarkable comeback.

After a lay day called by Stars ‘n’ Stripes, Wednesday 4th February 1987 saw a truly stunning spectacle as over 100,000 cheering Australians lined the port entrance to witness the dock-out of the boats as they headed out to the course. The 1987 Cup caught the public attention like nothing else and a huge global audience tuned in to see whether an historic victory could be claimed by Dennis Conner. In typical Australian style, the sporting messages to the Americans were bold whilst the support for the home team was intense – flags and banners adorned the harbour and sailing had never seen such scenes.

However, if Australian hopes were high, they were dashed immediately from the start. On the final approaches to the pin end of the line, Conner held the leeward position and after the dial-up, a perfect call from Scott Vogel on the bow saw the American boat dial away, gain speed and hit the line perfectly with Kookaburra III struggling for speed and astern. The only option was to tack away for the Australians and from there, Stars ‘n’ Stripes just sailed into the lead, covering loosely before electing to decline a tacking duel and clicking into more breeze on the right of the course. It was perfect sailing from the grand-master of the 12-Metre era with an incredible team of sailors at the peak of their sport and by the top mark they were an astonishing 36 seconds up. From there they gained on nearly every leg of the course, often just loose-covering and sailing the windshifts to perfection. The winning gun was taken with a 1 minute 46 second delta and the America’s Cup was returning to America and the San Diego Yacht Club. Pandemonium ensued, small craft appeared from everywhere and the scene going back into Fishing Boat Harbour in Fremantle was one of ecstatic chaos.

Writing years later in his book ‘Comeback’ Dennis Conner recalled the scene: “There were hundreds of boats all around as we turned and headed back towards Fremantle. They kept pace with us all the way in, even when we set our Merrill-Lynch spinnaker for the final triumphant run up the harbour. Tens of thousands of spectators turned out to cheer us in. They were waving their Aussie flags and yelling: “Good on yer Dennis,” “Good on yer Yanks.” I have seen homecomings before but nothing that resembled this. The Aussies were saying: “You beat us fair and square, well done, no hard feelings.” That spirit of Australian sportsmanship was something I'll always remember.”

After the prize-giving in Fremantle in the presence of Prime Minister Bob Hawke, and Dennis Conner receiving the Cup, the team returned to a hero’s welcome in San Diego as 60,000 supporters greeted the team at a reception. From there it was on to Washington D.C. the following day for a White House reception with President Ronald Reagan who hailed the sailors and the technological advances that Stars ‘n’ Stripes with its onboard computers and 3M supplied ‘riblet’ coating to the hull had delivered before the team travelled to New York for a memorable ticker tape parade down Fifth Avenue in New York arranged by Major Bill Koch and long-time backer of the Stars ‘n’ Stripes team, Donald Trump.

The ’comeback’ was complete. Dennis Conner became the first man in history to lose the America’s Cup and win it back again. The event was now stratospheric and the modern America’s Cup had well and truly begun.

A PRELUDE TO THE CUP - THE CHALLENGER AND DEFENDER SELECTION SERIES

Returning home, the Australia II team were greeted rightly as national heroes with huge parades in their honour starting in Melbourne, but it was in Perth, Western Australia where the sheer scale of their victory hit home as John Bertrand, the winning skipper wrote in his book ‘Born to Win’: “In Perth there was the most gigantic parade with estimates that almost half a million people witnessed the homecoming of the western Australian syndicate. Each member of the crew and every member of the backup staff had his own parade car with a big nameplate on the front. The crowd at Fremantle Town Hall went wild as we set off and they lined the route by the thousands all the way to the Esplanade in Perth. They roared and applauded as we entered the area selected for the grand finale but when Alan and Eileen Bond drove slowly in, standing in an open Rolls Royce and waving, the crowd went berserk. They chanted endlessly B-O-N-D-Y! B-O-N-D-Y! B-O-N-D-Y! It might have been the most exuberant welcome home since Julius Caesar re-entered Rome 47 years before Christ.”

For Bertrand it was the end of his America’s Cup journey for now. He simply had nothing more to give for the 1987 defence and stepped away from competition. He would come back in 1992 but a sinking in that regatta ended his professional Cup career.

For 1987, a new generation of Australian sailing talent emerged and whilst Alan Bond quickly built a new boat, Australia III, as a trial horse for Australia II in the big seas off Fremantle, his hopes were pinned on Ben Lexcen again producing a rocket-ship for his final design of Australia IV. Lexcen had de-camped to the Netherlands in late 1985 for extensive research at the Ship Model Basin at Wageningen and came back in April 1986 with a heavier displacement design, convinced that it would be appropriate for the big swells of Gage Roads, the sailing area, and the ‘Fremantle Doctor’ – the sea-breeze that came in as regular as clockwork in the afternoon.

The home-team, that had brought so much to success to Australia as a nation, were clear favourites in the public’s eye but if they thought they would have the defence trials all their own way, they were wrong. Kevin Parry, a wealthy businessman from Perth, saw the opportunity to take on Bond’s team with technology, and in the brilliant young talent of Iain Murray, a six-time 18ft Skiff World Champion, he found a superstar helm with a design background, more than capable of taking the fight to the Cup holders. The Taskforce ’87 syndicate was born and the resultant three all-golden Kookaburra 12-Metres were arguably some of the most beautiful ever built.

Hiring Lawrie Smith as a match-racing tune-up partner for Murray was another classy move by Parry and bringing the young Olympian and match-racing ace Peter Gilmour into the afterguard alongside Iain ‘Fresh’ Burns strengthened the decision making onboard. The final piece in the puzzle was Derek Clark, the British engineer with a computing background who brought performance analysis aligned with technology as well as onboard navigation expertise to the syndicate.

With Murray embedded in the Kookaburra design team, Kevin Parry appointed local up-and-coming Perth designer John Swarbrick and also called on the influential Alan Payne to advise on winged keel dynamics and run through a huge testing schedule of shapes and variations. The Taskforce ’87 syndicate was a well-run, highly secretive, logical, data-driven campaign but public sympathy in Perth and across Australia was firmly with Alan Bond’s team that promoted favourite Colin Beashel to the principal helm position with Gordon Lucas as tune-up helm.

Kookaburra’s design team spent time at the Netherlands Ship Model Basin running tank-tests but also took advantage of the Commonwealth Aeronautical Laboratory in Melbourne for the wing designs and the tank-testing facility at the Australian Maritime College in Tasmania. The first boat to come out of the testing in early 1985 was ‘Kookaburra I’ that was deemed to be close in performance to Australia II and could provide benchmark data as well as being an all-important crew-training vessel, but it was the launch of ‘Kookaburra II’ in late 1985 that gave the team vital two-boat testing opportunities in the real-world environment and unique conditions of Perth that catapulted the team forward. Secrecy was the byword of Taskforce ’87 and the decision not to race in the 1986 World Championship ramped up the intrigue around the syndicate.

Two other Australian syndicates also formed to compete for the Defence slot with Syd Fischer commissioning Peter Cole to tank-test what would become the voluminous ‘Steak ‘n’ Kidney whilst Sir James Hardy returned with a challenge under the ‘South Australia’ name. Both efforts showed glimpses of potential but under-funding ultimately determined their fate and were no match against the top two, well-funded defence teams that effectively went head-to-head for the right to defend.

Lining up against the Australians for the first America’s Cup outside of America since the founding race in 1851, was a remarkable set of challengers all eyeing the ‘new’ America’s Cup and the broad appeal that it would garner internationally as a sporting spectacle. Advances in media coverage, most notably onboard broadcast quality cameras, brought the 1987 America’s Cup to an entirely new audience and would inspire generations to come who, for the first time, saw both live and pre-recorded match-racing of this apex event. Fremantle was arguably the perfect venue for the America’s Cup and the images captured have remained part of America’s Cup folklore ever since.

Determined to avenge their defeat in 1983, the New York Yacht Club mounted a serious challenge with a budget reported to be in excess of $20 million, led by Richard de Vos and excusing the services of Dennis Conner. John Kolius was appointed as skipper for this three-boat campaign and the Sparkman & Stephens design office were secured to deliver the boat that they hoped would bring the Cup straight back to the West 44th Street clubhouse.

Dennis Conner, meanwhile, was forging a very different path to the 1987 Cup. Slighted by the New York Yacht Club in the immediate aftermath of defeat he wrote in his book ‘Comeback’ some years later: “Perhaps my greatest disappointment was the reaction of the Cup Committee from the New York Yacht Club. They simply abandoned me and all the guys. No-one even showed up to say: “nice try.” We’d done the best we could in a situation that their inaction and ineptness helped to create, but not one of them had the guys to face any of us.” Conner returned to his home club of San Diego and, with the help of close confidantes Malin Burnham, Fritz and Lucy Jewett determined that the 6000+ hours that he had sailed 12-Metre yachts since his first Cup foray with Mariner in 1974, through the 1980 Freedom campaign and on into 1983 with Liberty “almost demanded another attempt” as he put it.

Conner secured initial funding from Edsel Ford, scion of the Ford Motor Company, and selected Hawaii as his training base eschewing the option that other syndicates took to base themselves out of Perth. It was a masterstroke decision by the greatest campaigner in America’s Cup history with 22-28 knot winds every day to hone their seamanship and day after day training sessions were conducted. Conner appointed a trio of favoured yacht designers in Britton Chance, Dave Pedrick and Bruce Nelson. Pedrick was sent off to the tow-test tank facility at Escondido, California whilst Chance worked with Grumman Aerospace on keel design and the trio became known as the ‘Picassos’ with John Marshall, a long-time lieutenant corralling the geniuses as they set to work on what would become Stars ‘n’ Stripes ’87.

Whilst Conner schemed in Hawaii, several other American syndicates joined the rush to be a part of the 1987 America’s Cup. Conner’s long-time nemesis, the San Franciscan Tom Blackaller team up with Gary Mull for the ‘USA’ syndicate whilst America’s Soling star Rod Davis, fresh from winning a Gold medal with Robbie Haines, secured the services of Johan Valentijn to create the lavishly adorned ‘Eagle’ campaign. The great Buddy Melges challenged from the Chicago Yacht Club with his ‘Heart of America’ syndicate and after trying to get German Frers involved with the design, ultimately went with Scott Graham and Eric Schlageter due to nationality rules. The old Cup warhorse ‘Courageous’ was brought back for a fifth attempt on the trophy by the Yale Corinthian Yacht Club with Dave Vietor steering and a huge upgrade programme initiated by Leonard Greene with ‘Courageous’ getting numerous winged keels to trial.

Canada was back in the America’s Cup for 1987 with the merger of the True North syndicate of the Royal Nova Scotia Yacht Squadron and the Secret Cove Yacht Club’s ‘Canada I’ syndicate. Bruce Kirby, the designer of the Laser dinghy, was the naval architect behind a tank-test project that saw ‘Canada I’ undergo major surgery and resulted in such an altered form that it was re-named ‘Canada II.’ Terry Neilsen, the Laser World Champion and Finn bronze medallist in 1984, was installed as skipper.

France were back with two syndicates for 1987 with Marc Pajot challenging on behalf of the Société des Régates Rochelaises with backing from Serges Crasnianski, the founder of Key Independent System (KIS), the company that brought to the world the compact machine that cuts keys, prints business cards, and engraves bracelets and can be seen in thousands of corner hardware shops around the world. Crasnianski’s proposal was to call the syndicate ‘French Kiss’ and required an IYRU ruling to opine that the name didn’t contravene advertising rules in place at the time. Thankfully the French won a favourable ruling, and a legend of yachting was born with Philippe Briand rejecting tank-testing and, ahead of his time, trusting in computer simulation for the overall design.

Marc Pajot’s elder brother, Yves, also secured seed funding in France to challenge under the flag of the Société Nautique de Marseilles and hired the mercurial Daniel Andrieu to design what would become Challenge France. Andrieu had dominated the IOR world through the 1980’s and there was much hope that the design would deliver success, but an acute shortage of funds saw the team go bankrupt before the Challenger Selection trials had even begun and the team limped through the competition.

After a positive showing at the 1983 regatta and impetus from the Victory ’83 challenge, Britain came back for 1987 with Graham Walker funding the White Crusader challenge under the flag of the Royal Thames Yacht Club. Harold Cudmore was brought in to lead the campaign alongside Phil Crebbin. Ian Howlett was commissioned to design a ‘conventional’ 12 Metre ‘Crusader I’ whilst Dave Hollom went radical with the design for ‘Crusader II’ and used the National Maritime Institute for tank testing what would become known as ‘The Hippo’ – named after the hippodrome shape of the hull. Ultimately, and after political internal wranglings that so often scupper British challenges, the more conventional route was adopted, and ‘Crusader I’ was selected for the Louis Vuitton Cup series.

Italy made a big splash at the ‘87 Cup, principally due to the Yacht Club Costa Smeralda being selected as Challenger of Record (against fierce competition from the Americans – and in particular the San Diego Yacht Club). Andrea Vallicelli was again brought in by the money-no-object Azzurra syndicate ultimately financed by the Aga Khan, to work-up three boats for the syndicate under the in-out-in-again skippers of Mauro Pellaschier and Cino Ricci. The second Italian challenge came from the Yacht Club Italiano syndicate with two yachts: Italia and Italia II with the backing in part of the Gucci fashion house. Ian Howlett was initially drafted in early for design work on ‘Italia’ before the design partnership of Giorgetti & Magrini took over for the ill-fated ‘Italia II’ that, upon launch, was dropped from its crane and sank – a setback she would never recover from as ‘Italia’ was nominated for the Louis Vuitton Cup series.

The final challenge, from New Zealand, was ultimately to be the most controversial through the 1986 and 1987 seasons. Always the innovators, New Zealand heralded a new dawn in 12-Metre construction by opting to build in glassfibre and caused what duly became known as ‘Glassgate.’ With a syndicate of first-class designers in Bruce Farr, Laurie Davidson and Ron Holland brought together, they found in Chris McMullen of McMullen & Wing, an exceptional yacht builder that could handle the build of not one, but two 12-Metres in glassfibre that were quick straight out of the box. At the 1986 World Championships, with minimal preparation in Perth, the 24-year-old Chris Dickson won two races aboard KZ-5 ‘Kiwi Magic’, the newer of the Kiwi boats, and ultimately ended up second to ‘Australia III’ overall. It was a stunning result and caught the attention of Dennis Conner who didn’t compete at the ‘86 Worlds and who made it his mission to go to war with the team, Lloyds Registry and anyone else to try and needle the Kiwis.

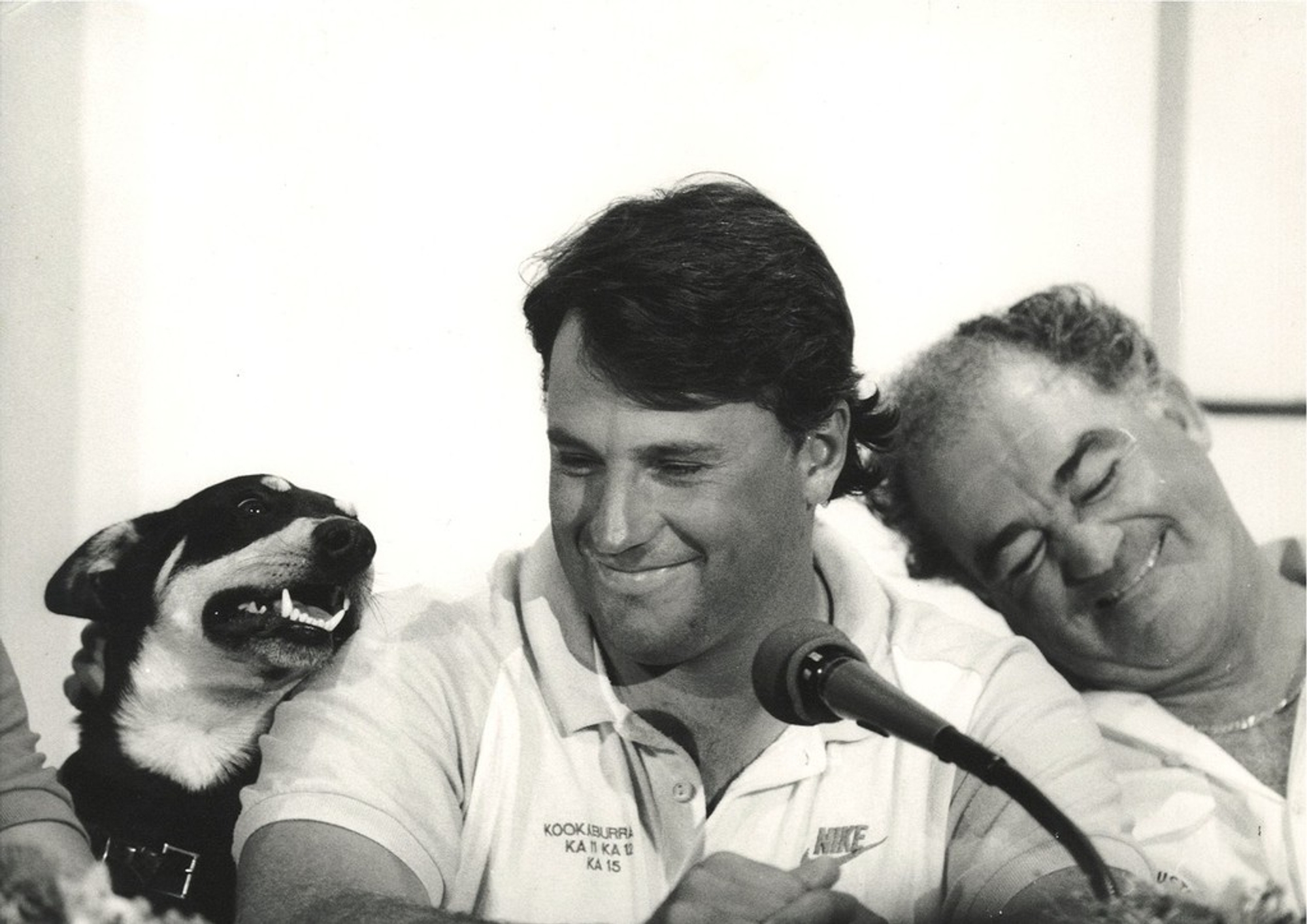

A famous press conference set the tone ahead of the Louis Vuitton Challenger Selection Series with Conner unable to restrain himself saying: “There have been 78 12-Metres built, all of them aluminium. Why would you want to build in glass…unless you wanted to cheat?” This stung the New Zealand challenge, led by the combative Sir Michael Fay, who refused all core samplings and the truth of the matter, subsequently discovered, was that the New Zealand boats were probably the most compliant 12-Metres ever built owing to the variances in aluminium construction. That they were fast, was more down to the Kiwi sublime boat-handling and technique than any significant advance that the glassfibre construction could deliver. At the time though, Conner, who had been blind-sided by innovation before, was waging all-out war.

As the Defender and Challenger trials begun, Fremantle came alive and brought sailboat racing to a new technicolour age that captivated TV audiences around the world. Gage Roads was, and is, an uncompromising place to sail and the regular 26-28 knots winds blowing in on the Fremantle Doctor alongside wave heights that regularly hit 6 feet, were a made-for-television spectacle that had far-reaching consequences and interest that has lasted to the present day.

The Defender trials however were one-way traffic with the Kookaburra syndicate unarguably the team to beat despite so much local support for Alan Bond’s all-conquering Australia team. Colin Beashel took charge of Australia IV for the four-way battle between Kookaburra II, Kookaburra III and Syd Fischer’s Steak ‘n’ Kidney and led her to the final against Kookaburra III where she was trounced 5-0 by the aggressive starting tactics of Peter Gilmour and the undoubted tactical brilliance of Iain Murray, Iain Burns and Derek Clark. The Royal Perth Yacht Club had effectively hedged its bets by supporting both syndicates and entered the America’s Cup Match hopeful, rather than expectant, of victory against the challenger.

The Australian club’s doubts were magnified by the spectacle of the most compelling Challenger Selection Series in the history of the competition. New Zealand’s ‘Kiwi Magic’ led through the early rounds losing only one race ahead of the final – an incredible record – and looked set fair to continue their dominance of the regatta. The New York Yacht Club’s ‘America II’ finished the preliminary and opening round in second place whilst Stars ‘n’ Stripes ended third and Marc Pajot’s ‘French Kiss’ sealed fourth.

By round three, Tom Blackaller’s ‘USA’ gate-crashed the top four whilst Dennis Conner moved up to second and ‘French Kiss’ in fourth, thus eliminating the likes of Italia, White Crusader, and remarkably, the well-funded America II. Kiwi Magic were still the team to beat and, in the semi-finals, they faced down French Kiss having won 33 from 34 races in the Louis Vuitton Challenger Selection Series. Pajot put the pressure on Dickson from the outset, launching a protest flag on the first ten-minute gun to protest the illegality of the ‘Plastic Fantastic’ (the protest was dismissed and threats of going to the New York Supreme Court for a ruling never materialised) but superior crew-work and an undeniably fast boat, saw the Kiwis ace the series 4-0 and go into the final as firm favourites.

Meanwhile in the other semi-final, Dennis Conner faced down Tom Blackaller whose ‘USA’ 12-Metre featured a canard – an adjustable rudder situated forward on the bow that supposedly reduced leeway and had been one of only two boats to beat Stars ‘n’ Stripes in the second Round Robin – the other, of course, was Kiwi Magic. Blackaller’s boat looked to have inherent speed in certain weather windows, but Stars ‘n’ Stripes re-ballasted for heavier conditions ahead of the semi-finals and it was a telling decision as USA struggled in anything above 17 knots and fought the seaway. However, an opening race that Conner shaded by 10 seconds was only won on the final leg as the breeze built to 18 knots but after that Stars ‘n’ Stripes was away at the races, winning four straight and securing their place in the Louis Vuitton Cup Final.

The acrimony between the Kiwi Magic team and Stars ‘n’ Stripes rumbled on ahead of the Final but with the summer breezes blowing hard, the opening exchange of the first race pre-starts was remarkably mild. Chris Dickson entered with a stunning 37-1 winning ratio, and many believed that victory was a foregone conclusion, whereas Conner had steadily improved round after round, bringing in more ballast for the conditions and slowly bringing better big breeze technique and his vast experience to the fore. The Kiwis relied on crew work improvements to match the Americans. The first start saw Conner take the Committee Boat end of the line on port whilst the Kiwis went to the pin end and tacked. By the first cross, Dickson was forced to duck and from there, Conner masterfully eased away showing pin-point match-racing skills to win by 1 minute 20 seconds and hand the Kiwis their second defeat of that summer.

Race 2 was a close affair, but better positioning put Conner ahead to windward on a long drag race on starboard tack off the start line and eventually forcing the Kiwis to tack away to clear. It was text-book sailing from Conner with Tom Whidden calling the shots and Peter Isler navigating and they secured a 2-0 lead by 36 seconds. The Kiwis called a lay-day in a search for more speed and by the time race three was sailed in big breezes, only gear failure onboard Stars ‘n’ Stripes prevented the Americans from winning. A final beat that saw an astonishing 55 tacks thrown in by Conner with Dickson defending like a banshee resulted in Kiwi Magic taking the win and closing the gap to 2-1.

Race four of the Louis Vuitton Cup Final was a race of attrition, sailed in winds of 26-28 knots that saw Conner win the start and then just power up the first beat, seemingly higher and going faster to lead by 23 seconds at the top mark. The Kiwis were struggling with gear failure, taking their backstay out on a gybe and having genoa sheet issues before tearing their mainsail to shreds on the final beat. The resultant 3 minute 38 second victory by Stars ‘n’ Stripes was non-reflective of the relative speeds but proved why Fremantle was such a demanding venue.

And so it continued into race five that was, to many, a classic and a defining race of the 1987 America’s Cup. Conner won the start, set-up to windward on a long drag race in big breeze and a building sea state, to lead by 42 seconds at the windward mark. The ‘Plastic Fantastic’ came back downwind but it was the third leg where the drama happened as Stars ‘n’ Stripes blew their number 6 genoa to shreds and the bow was a sudden desperate flurry of activity as Conner recalled: “Sure enough, our jib exploded like a lightning strike in a thunderstorm. The stitching came out of the vertical mitre on the foot and bam! it was gone.” All that was left was a narrow ribbon of Kevlar on the forestay but the years of training in Hawaii came to bear and the superb Stars ‘n’ Stripes crew not only had a new jib up before Kiwi Magic could capitalise but also held position to cross on port tack. The deficit had gone from 48 seconds to just 14 seconds ahead of the first two reaches. The Kiwis opted for a gennaker and held high on the reach whilst Conner opted for a spinnaker that would only benefit him on the second reach down to the leeward mark. The Americans held on with the inside berth at the wing mark and threw up a huge quarter wave behind whilst keeping an initial high angle off the gybe and then capitalised by running square down to the America’s Cup leeward rounding buoy.

With so much pressure on his 25-year-old shoulders, Dickson made his first crucial error of the entire summer, coming into the leeward mark and hitting it as he rounded, that required him to re-round. In wind touching 31 knots it was an agonisingly slow re-round and Stars ‘n’ Stripes played it cool with a loose cover up the final beat to take the gun and the Louis Vuitton Cup 4-1. A masterful destruction by the man who would become known as ‘Mr America’s Cup.’ Chris Dickson was gracious in defeat, acknowledging the Kiwi speed deficiency and saying: “I guess 13 years’ experience, beat 13 months’ experience.”

Having been accused outright of ‘cheating’ by Conner, the New Zealand team were reluctant to follow the protocol of the beaten challenger helping the successful one – a tradition that had been in place since the first multiple challengers appeared in the 1970’s. Citing the ANZAC Alliance, Dickson’s team trialled with Kookaburra III ahead of the Match and came away with the distinct impression that Australia had little chance against Stars ‘n’ Stripes. The Americans corralled the other American syndicates buying certain sails from both USA and America II and all was set for the Match of the 26th America’s Cup.