THE FIRST CHALLENGE FOR THE OLDEST INTERNATIONAL SPORTING TROPHY

Almost immediately after that thrilling victory in the late evening gloom of August 22nd 1851, the yacht America was sold to a new owner, a 39 year old Army Captain Lord John de Blaquiere, for the sum of £5,000 and Commodore John C. Stevens returned to New York in September 1851 with the £100 Cup.

At that time, the Cup belonged as the property of Stevens and the five other owners of the America – Edwin A. Stevens, George L. Shuyler, Hamilton Wilkes, J. Beekman Finlay and Col. James A. Hamilton. They displayed the magnificent ewer in rotation at celebratory in-house dinner parties, the most famous recorded being at the Astor House in 1851, as each had a sense of ownership over the trophy.

The Cup itself was described in The Lawson History of the America’s Cup (The Lawson) as being: “twenty-seven inches high, thirty-six inches circumference of body and twenty-four inches of base, and weighs one hundred and thirty-four ounces. It is not a cup, properly speaking, but a cylindrical vessel, open at both ends, and incapable of holding liquids. It was made in 1851 to the order of the Royal Yacht Squadron by Messrs. R&S Gerard, Panton Street, London and bears the makers’ stamp, as well as the English hallmark.”

That the Cup survived this period is of note as it is recorded that thought was given about melting the ewer down and awarding medals: “properly stamped or engraved with date and inscription commemorative of the race in which the Cup was won,” according to The Lawson.

Thankfully this idea failed to progress, but it wasn’t until July 8th, 1857, that the Cup, at the behest of George L. Shuyler and the surviving members of the America syndicate, was conveyed to the safe-keeping of the New York Yacht Club as an international trophy with a strict set of conditions that lasts to this day. The ‘original deed of gift’ as it was known has dictated the direction and prestige of the America’s Cup ever since despite several updates that we will cover in subsequent articles.

On the 21st July, 1857, notice was sent out by the New York Yacht Club to all foreign clubs to invite ‘spirited contest for the championship’ and promising all challengers: ‘a liberal, hearty welcome and the strictest fair play.’

No challenge was forthcoming. The English were licking their wounds and going back to the design-board after the defeat by America in 1851 and the American Civil War between 1861 and 1865 rendered the pastime of yachting as periphery to the national discord. It wasn’t until the winter of 1866 that the first green shoots of recovery began to emerge with the then Commodore of the NYYC, James Gordon Bennett, initiating an ocean race between three schooners for the massive sum of $90,000.

But it was the arrival in English waters of the schooner Sappho, the largest yacht ever built up to that time in the United States with a length at deck of 133 feet and 9 inches, in the summer of 1868 that really started the race for the America’s Cup and its first challenge. Laden with ballast, the Sappho raced the English fleet around the Isle of Wight and was soundly beaten by four schooners, most notably the Cambria owned by James Ashbury, the Conservative politician and heir to the Ashbury Railway Carriage and Iron Company Ltd fortune.

What followed that race was a firing of competitive spirit between the English and the Americans with Ashbury, bitten by Cup fever, issuing a schedule of challenges in October 1868 to the NYYC combining ocean races, the Isle of Wight yachting season and a race for the ‘America’s Queen’s Cup of 1851.’ Asbury’s communication stated, according to The Lawson: “If I lost I would present the New York Yacht Club or the owner of the successful vessel with a cup, value 100 guineas…”

The New York Yacht Club, disregarded the offer of ocean racing, replying that it: “could only take cognizance of and respond to that portion of said communication having reference to the Challenge Cup won by the America.’

Communication continued between the NYYC and James Asbury into 1869 with the Englishman writing that he hoped to sail under the burgee of the Royal Thames Yacht Club and that if he should win, the Cup would be donated to the club and then races of not less than 300 miles would be sailed in the English Channel or any other ocean.

Furthermore, Ashbury had stated that he wanted to sail the NYYC’s champion schooner for the America’s Cup in a one-on-one match to which the club was less than enamoured, preferring that the English yacht race against a fleet. Subsequently this position was reversed as the NYYC could not uphold this stipulation or interpretation in the original deed of gift and was viewed as perhaps being unsportsmanlike. Ashbury too came away from the matter with little grace as the one trying to dictate terms to alter the deed of gift should he have won. Whatever, no racing took place in the summer of 1869, but Ashbury returned to the challenge in the winter of 1869 stating that he would race across the Atlantic against the 123-foot fast-keel schooner ‘Dauntless’ and then wished to challenge for the America’s Cup in May 1870.

Ashbury continued to push the rules stating in a communication to the NYYC that: “The Cup having been won at Cowes, under the rules of the R.Y.S; it thereby follows that no centre-board vessel can compete against the Cambria in this particular race.”

Again, the NYYC returned to the original deed of gift that the match “is to be sailed according to the rules and sailing regulations of the club in possession” and that it could not exclude from the race any yacht duly qualified to sail under the rules and regulations of the New York Yacht Club.

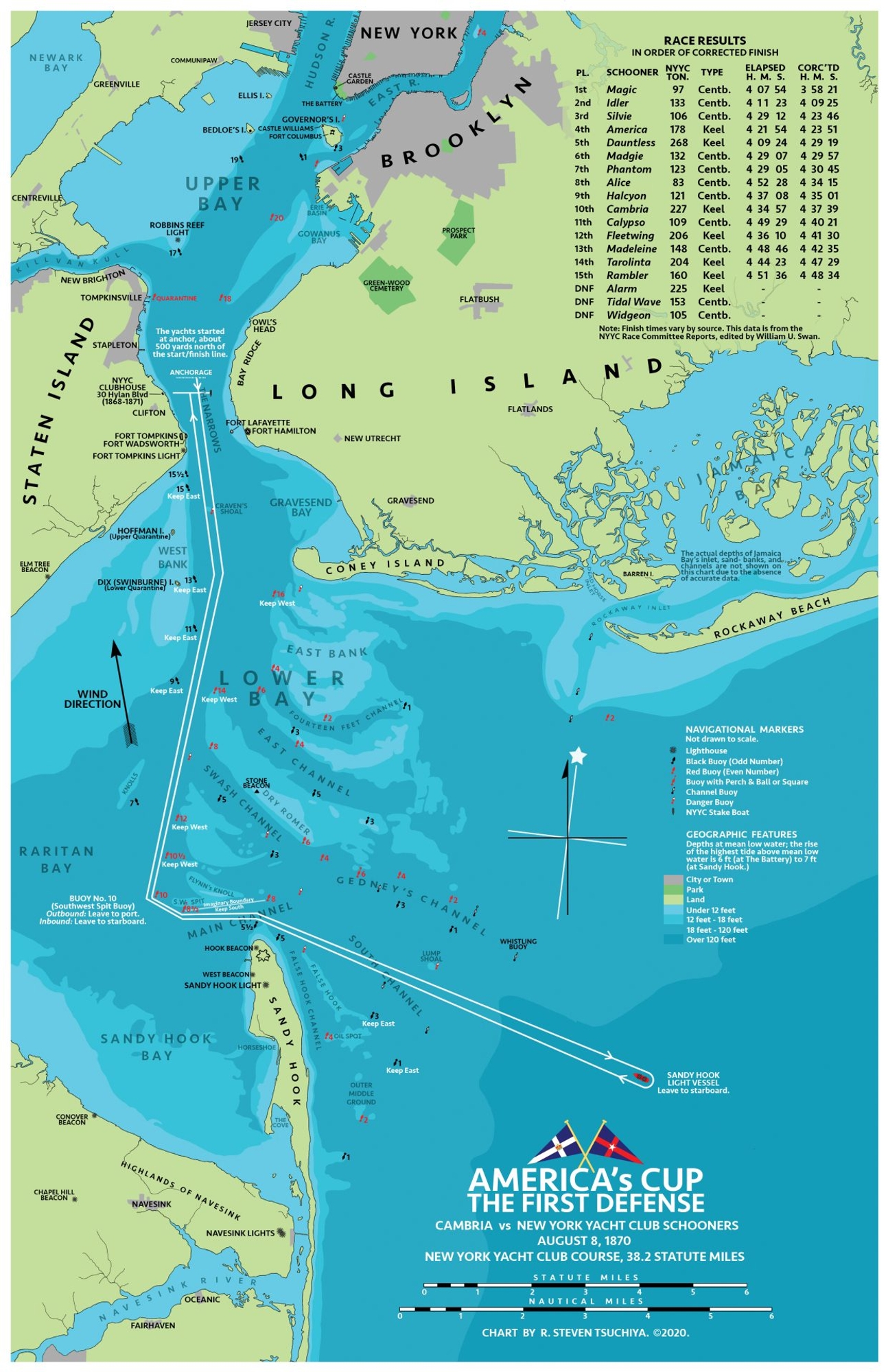

Regardless, Ashbury set sail in Cambria for America in a race against Dauntless from Daunt’s Rock to Sandy Hook, starting on 4th July 1870. Cambria won, having taken a shorter northerly route and both boats were ready to sail for the America’s Cup on 8th August 1870 – the first race in American waters for the Cup.

J.D. Jerrold Kelley, writing in the 1884 book, ‘American Yachts’ gave a thrilling account of that first race that attracted significant public interest in the spectacle: “the public prayer being for any yacht to beat the representative of the Royal Thames Yacht Club, but best of all that it might be the America.” According to Kelley, 25 yachts had entered the race but only 18 made the start-line at anchor, 50 yards apart including the ‘rakish schooner’ America and “choice of position had been granted the Cambria, and Mr. Ashbury had taken that nearest the clubhouse, and next but one to the shore.”

It was a poor decision. As the starting signal roared at 26 minutes past 11am, on the very last of the ebb tide, the windward boats shot off leaving the Cambria, the last to get away. It was a deficit that was never made up. Magic, the 79-foot, 92.2-ton sloop, centre-board design having been re-built in 1869 at City Island by David Carll, was something of a surprise package having previously had a less than stellar racing pedigree. Her victory on the water over Dauntless of 1 minute and 29 seconds was amplified on corrected time, whilst the Cambria arrived 8th on actual time and 10th on corrected. The America’s Cup was safely in the possession of the NYYC.

According to Kelley’s account: “guns roared, men cheered, bells rang, and bands burst into loud and brazen notes of triumph; and when the Magic rounded the lightship, making it almost a certainty that the Cup was safe, there arose a shout painful in its intensity of delight, for it was the relieved outcome of pent-up excitement which had reached its culmination at this very point.”

Despite the loss, and much to the sportsmanlike behaviour of Ashbury, he went on to race a further eight races throughout the summer of 1870 against American vessels, putting up wagers and challenge cups. He lost them all, but it was noted that “Mr. Ashbury raced his vessel for all she was worth and put up trophies with great liberality and spirit,” according to The Lawson.

James Ashbury determined to return with an improved yacht, and the spirit of friendly competition was evident as the mayor of Brighton stated in a speech at a dinner given in his honour back home in England in January 1871: “The President of the United Stated (Gen. Grant) did our friend the honour to breakfast with him on board the Cambria, and that is good enough testimony that no jealousy was created by the yacht race.”

Ashbury though was bruised by the encounter stating to the NYYC that he felt the conditions under which he had sailed that year were such that he had “faint hope of winning.” A lingering sense of injustice was also recorded that the Cambria had been fouled early in the race although Ashbury did not protest, despite apparently being on starboard.

As a result, in the winter of 1870-1871, Ashbury remained in correspondence with Commodore Bennett of the NYYC urging the club to put up a representative vessel rather than a fleet for the race for the America’s Cup.

By March 1871 and following an opinion on the original deed of gift by the only surviving member of the founding America syndicate of owners, George L. Shuyler, the NYYC resolved “that we sail one or more representative vessels, against the same number of foreign challenging vessels.”

The die was cast for the future of the America’s Cup.

To be continued…

READ MORE ABOUT THE 1871 CUP: THE CUP GETS UGLY – THE 1871 CHALLENGE