THE CUP GETS UGLY – THE 1871 CHALLENGE

James Ashbury was nothing, if not a colourful character in the history of the America’s Cup. He had inherited a large fortune and a considerable business, the Ashbury Railway Carriage and Iron Company Limited, from his father who died in 1866, but ill health and a desire to climb within highfalutin social circles led to him re-locating from Manchester to the South Coast of England in Brighton and concentrate his boundless energy on yacht racing.

His first foray into the America’s Cup had not been successful on the water, however off it, he had gained great standing for his grace and sportsmanship. His second challenge was a very different affair. Bruised by the encounter with the fleet from the New York Yacht Club, Ashbury commissioned a new vessel from Michael Ratsey of Cowes, Isle of Wight in 1870 and the result was the Livonia (named after a province in Russia where Asbury had made considerable money on a building contract) that was launched on April 6th 1871.

Livonia is recorded in the Lawson History of the America’s Cup as having: “a full, rounded midship section, a long bow, straight sheer, and a fairer counter than most English schooners, while she was heavily sparred, with sails of American cotton having a total area of 18,153 square feet.” It was as close to an American build as English shipwrights would allow, with a form taken from Cambria and parts akin to Sappho. The NYYC were nonplussed and deigned to meet this challenge with materials at hand. No defender was built to meet the challenge.

But in challenging, Ashbury decided on a maximum attack strategy, vowing to avenge his defeat where he is on record as saying that he had: ‘faint hope of winning’ – the lament of many a challenger since. Racing against a fleet of American boats was the first issue that Ashbury set out to correct and it was an interpretation of the Deed of Gift from George L. Schuyler, the only surviving member of the original America syndicate that was required.

In March 1871, Shuyler delivered a stunning verdict saying: “I think that any candid person will admit that when the owners of the America sat down to write their letter of gift to the New York Yacht Club, they could hardly be expected to dwell upon an elaborate definition of their interpretation of the word ‘match’ as distinguished from a ‘sweepstakes’ or regatta; nor would he think it very likely that any contestant for the cup, under conditions named by them, should be subjected to a trial, such as they themselves had considered unfair and unsportsmanlike…It seems to me that the present ruling of the club (to sail a fleet against a challenging vessel) renders the America’s trophy useless as a challenge cup.”

The NYYC bowed to the sage words of Schuyler on the 24th March 1871 but a crucial communiqué on June 7th 1871 between Ashbury, dated in London, and James Gordon Bennett, Commodore of the NYYC would prove to be crucial to the future of the America’s Cup. In the final acceptance of the challenge, Bennett wrote: “The New York Yacht Club consents to waive the six months’ notice and accepts your challenge as representative of Royal Harwich Yacht Club to race for America’s cup next October.”

In accepting a challenge submitted on behalf of one single club, it set a precedent but this challenge was about to turn ugly. Ashbury, as Commodore of the Royal Harwich YC and under whose burgee the Livonia raced, reviewed the correspondence in August 1871 and informed the NYYC that he would come as a representative of ‘several clubs’ honoring him with certificates of registration. Ashbury’s intention was to race in a series of 12 races, seven to win, under the different flags of the British clubs, one race for each club, with the cup to go to the club under whose colours he sailed in the winning race.

The yacht clubs that James Ashbury sought to represent were: the Royal Albert, The Royal Yorkshire, The Royal Victoria, The Dart Victoria, The Royal Harwich, The Royal Western of England, The Royal Western of Ireland, The Barrow Western of Ireland, The Royal Mersey, The New Thames, The Royal Thames and The Royal London.

The NYYC were not impressed with the dictation of terms and held an informal meeting on August 27th, 1871, that kicked the final decision down the road to the club’s formal meeting on October 4th, 1871. Ashbury set sail for America on the 2nd September 1871, arriving in New York on the 1st October 1871 with his proposal hanging in the balance. When the final decision was made to only accept the challenge, as originally issued, from the Royal Harwich YC, it was accompanied by an incendiary line that Ashbury bristled at: “the fact that the deed of gift of the cup carefully guards against any such sharp practice.”

Threats of sending Livonia back to England and backward and forward communications proposing alternative formats for racing did little to staunch the acrimony brewing in October 1871 but a final ultimatum from the NYYC ended the matter: “The NYYC desire to be distinctly understood that they sail these races with you as the representative of the Royal Harwich YC only…” Ashbury finally accepted this but the mystery of why he was so insistent on challenging under the flags of twelve clubs remains. Theories have been offered centring around the NYYC’s resolution to sail against Ashbury with a fleet in the previous challenge, something that English yachtsmen never quite forgave and that he had every right to try and equalize the terms. Ultimately it was a fruitless but acrimonious episode and the NYYC instructed a best of seven races to be conducted in a final terse statement.

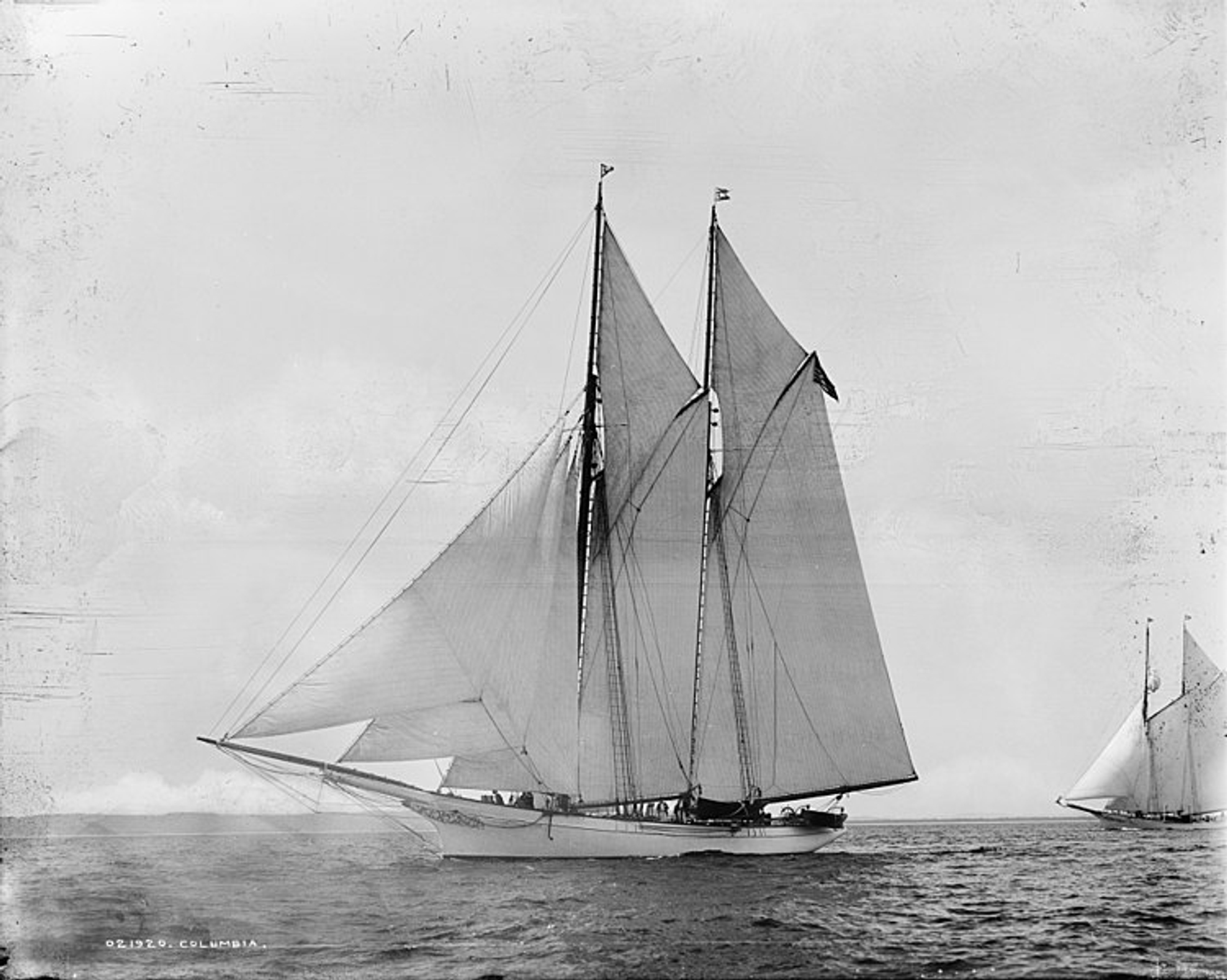

On October 16th the first race was set with the NYYC bringing to the line two vessels – Sappho and Columbia – before the committee decided which would face the Livonia. They selected Columbia for its light-weather prowess and it was a wise choice, delivering a thundering victory of some 25 minutes 18 seconds actual time – even better on corrected.

But it was race two that added fuel to the descending spirit around this cup contest and caused Ashbury to issue a protest. Columbia was again selected to race but in the pre-start an extraordinary clarification was sought with regards the course. The Lawson documents it thus: “Previous to the start, when the owner of the Columbia brought the written instructions on board, his captain after reading them, said; “there is no direction as to the turning mark, how shall I turn it?’” The owner, Franklin Osgood, returned in his gig to board the committee boat and returned with the instruction: ‘Turn as you please.’

With this knowledge, conditions conspired for it to be a crucial instruction. As the boats hared off on the opening reach with Livonia holding a lead, Ashbury was safe in the accepted knowledge that in England the rule stated that when no instruction was given that marks should be left to starboard. As the turning mark approached this meant a serious gybe for Livonia that left them drifting far leeward of the mark-boat with all sheets flowing and faced the prospect of luffing hard to trim flat for the windward leg home. Columbia cut in between the mark and the Livonia’s stern, tacked around the mark and set up for a hard beat home in heavy, unfavourable conditions. The day should have been Livonia’s but the record shows Columbia winning by a margin of 5 minutes and 11 seconds on actual time.

The protest subsequently submitted by Ashbury was not upheld and this caused much consternation amongst the right-thinking yachting scribes of the day with many, published in American journals, questioning the American’s sportsmanship. The NYYC stuck to its guns and issued a lengthy clarification on October 18th, 1871, highlighting the infamous Nab Tower miss by America in the original £100 race in 1851 alongside their interpretation of the unique nature of racing in sweepstakes or regattas. Flames were fanned further as the NYYC’s statement claimed: “The committee have dwelt at some length on this matter because, although by the rules of this club there is no appeal from their decision, Mr. Ashbury not only declined to accept it as final, but made it the foundation of communications to them through the press, which were of a disagreeable character generally, threatening to appeal to tribunals unknown to this club for redress against what he deemed unjust treatment.”

Ashbury was fuming but come the morning of October 19th, 1871, there was a twist in this Cup saga as the designated pool of vessels that the NYYC could pick from was depleted through either bad luck or unpreparedness. Sappho was in dock, Palmer’s sails were torn and Dauntless had a tear or ‘rent’ as was described in her mainsail. This left Columbia, the light-weather flyer, as the only option to race Livonia but she too was a mess with slack rigging from the day before, her foremast sprung at the hounds and her sailing-master, Nelson Comstock, out injured. Columbia did not expect to race but pressed into action, she was staffed by what was later described as ‘too many amateurs’ – the America’s Cup is no place for amateurs.

This third race was something of a sham for the under-prepped Columbia. Having almost capsized on the first reach, the crew stood by as the fore-gafftopsail split, followed by the flying-jib stay crashing overboard, before the steering-gear broke on the run back to the finish. When the maintopmast-staysail sheet parted, shattering the sail into ribbons, the crew called it a day, lowered the mainsail and the record stands that Livonia won the race by 15 minutes and 10 seconds. The Lawson History of the America’s Cup records: “This ended Columbia’s connection with cup racing.”

Things were, however, about to turn bizarre in this most extraordinary of America’s Cup series. From the final correspondence on October 10th 1871, in effect the ‘ultimatum’ with the NYYC ahead of the racing, it had been agreed that seven races would be sailed with the first to four taking the Cup. In the next two races, Livonia was soundly beaten in the breeze by the schooner Sappho with recorded victory times of 30 minutes 21s and 25 minutes 27s but Ashbury was not done. Whilst on paper and to the instruction of the New York Yacht Club the America’s Cup had been retained, Ashbury informed the committee by way of serving notice on the 23rd October 1871 to the NYYC that he would be on the start-line for ‘race number six’ and would sail a twenty mile course whether any yacht was there to meet him or not. Furthermore, Ashbury intended to sail the following day too, to complete seven races.

Dauntless, the fast-keel schooner, agreed to race in a private match and won convincingly by over 10 minutes but Ashbury was to claim that his boat went over the course alone so far as the club was concerned so should be awarded a cup race. Then the next day, October 25th, 1871, another private race was scheduled between Livonia and Dauntless, however the weather was so bad that a mark-boat could not go out. Asbury again claimed another cup race. In summation, the chancing Englander claimed the America’s Cup in a letter to the NYYC stating that he should have been awarded race two, won race three and had secured two further victories in races six and seven by default. It was a spurious claim at best. The NYYC ignored Asbury and made no reply to these claims beyond acknowledging receipt of his letter.

On his return to England, Ashbury ruminated on his treatment and again wrote to the NYYC claiming “unfair and unsportsmanlike proceedings” and also stated that if he ever came again to challenge for the cup he would: “bring his legal advisers with him.”

James Lloyd Ashbury never returned to challenge for the America’s Cup, instead pursuing a political career that saw him elected for a single Parliamentary term as the Conservative member for his hometown constituency of Brighton from 1874 to 1880. After leaving the British Parliament following a general election, Ashbury pursued his business interests, but disaster awaited as an investment in a large sheep station on the South Island of New Zealand led to bankruptcy.

He died in 1885 as a ‘gentleman of no occupation’ having taken his life with an overdose of chlorodyne – a sad end to a truly swashbuckling character in the history of the America’s Cup.

CONTINUE WITH 1876: CRUCIAL CHANGES – THE SECOND DEED OF GIFT