CRUCIAL CHANGES – THE SECOND DEED OF GIFT

The acrimony that lingered after the James Lloyd Ashbury challenge of 1871 saw a significant cooling of Anglo-American relations in the sport of competitive yacht racing resulting in the British sitting out the next two challenges that came from the Canadian lakes between 1876 and 1881. The records of the time stated that: ‘the English did not seem inclined to regard the game worth the candle in challenging for it,’ and they sat as interested spectators to the Cup.

This period was, however, something of a watershed period for the contest, and indeed the New York Yacht Club itself, despite the Canadian attempts being described in The Lawson History as: ‘the weakest efforts ever made to win the Cup.’ However, the vitriol that the NYYC had endured, both internally within the club and in the wider press of the day, during and post the 1871 challenge, gave the club a wake-up call. What resulted was a renewed sense of fairness (to a point) being adopted around how to accept challenges for its now embedded challenge trophy that was viewed amongst a receptive public with national pride and reverence.

The Lawson History of the America’s Cup records that by 1876, ‘the club was quite ready to make concessions, and did so in a measure that showed time and reflection to have given it a broader view.” Indeed, by the end of this period, a second Deed of Gift was called for after the trophy was given back to George Lee Shuyler for re-conveying and these changes were to prove seismic through the history of the America’s Cup, even to this day.

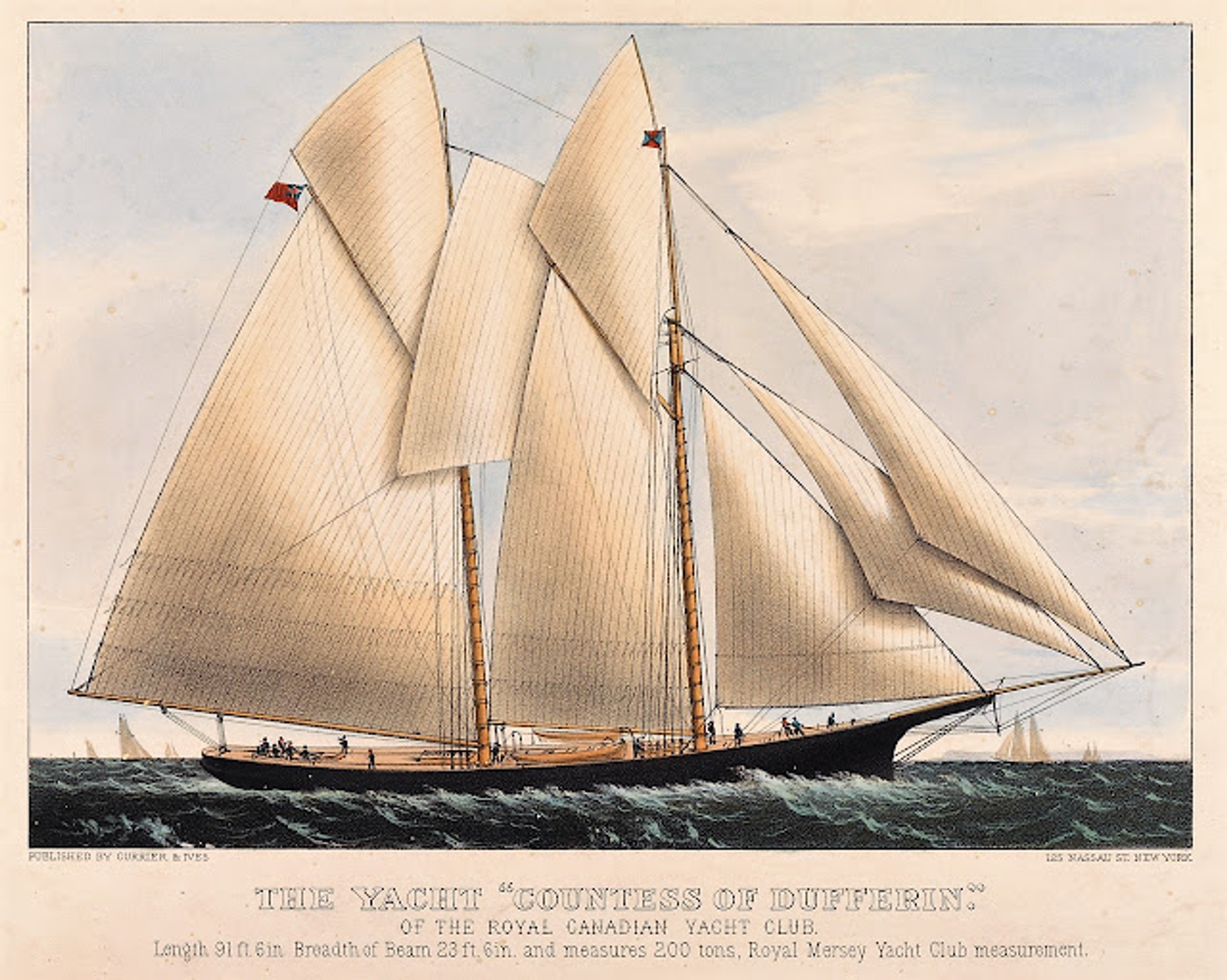

The Canadian challenges most notably saw a shift in boat styles from the schooner to the sloop although both challengers – the Countess of Dufferin (schooner) of 1876 and the Atlanta (sloop) of 1881 – were inland boats brought down from the Canadian lakes and of such varying quality that they were ridiculed by the millionaire owners, their crews and the old salts in New York.

The Countess of Dufferin after being transported from Lake Ontario, set sail from Quebec and arrived on her own hull and under her own sail around the coast of Nova Scotia to New York in under a month to a firestorm of ridicule. On arrival The Lawson History documents the ‘old barnacles’ saying that: ‘She had fresh water written all over her…her sails set like a purser’s shirt on a handspike…and her hull lacked finish being as rough as a nutmeg grater.’

Despite this the sailing fraternity of the New York area ‘prepared itself to see a formidable vessel, investing the stranger with those attributes of prowess which defenders of a citadel are wont to attribute to an aggressive foe.’

The crucial differences for the 1876 Cup races were two sportsmanlike gestures from the New York Yacht Club that set precedent going forward of which some would be enshrined into the new Deed of Gift in due course. First, the club had agreed to waive the customary six month notice period as they felt it unnecessary to build a new vessel and were confident of a successful defence. Second, they would name a single defending yacht in advance to meet the challenge. This however wasn’t straightforward after the NYYC had initially agreed that ‘a yacht would be at the starting-point on the morning of each race to sail the match.’ Subsequently at a later committee meeting of wise heads at the NYYC it was decided to name just one yacht for the series and this is a statute that stands to this day in the America’s Cup.

The 1876 Canadian challenge was roundly seen off in a three-race series by one of the smartest schooners in the New York fleet – the 106 foot overall, 95 feet at waterline ‘Madeleine,’ owned by John S. Dickerson – that had started out as being built as a sloop but was subsequently lengthened and hipped. Madeleine was a weapon of a boat replete with ‘copper on her bottom that was burnished until it shone like gold.’

Over just two Cup races the Madeleine aced the Countess of Dufferin, skippered by Captain Alexander Cuthbert and owned by Major Charles Gifford vice-commodore of the Royal Canadian Yacht Club of Toronto, and the Cup was secure. Cuthbert was given comfort by the scribes of the day, writing in the journals who widely regarded the challenge as a most gentlemanly and sportsmanlike Cup contest. The Canadians would be back five years later after a complex series of events regarding the ownership of the Countess of Dufferin that was eventually sold and returned to the lakes where she competed well for many years in her class.