THE CUP COMES ROARING BACK

If the mismatch of 1988 was a low-water mark for the modern America’s Cup, 1992 was to prove a remarkable and welcome shot-in-the-arm for the event and its future. Learning its lesson quickly, the San Diego Yacht Club nailed down a Protocol for multiple challenges, defined the rules of engagement and appointed a Trustee Board consisting of the club, the New York Yacht Club and the Royal Perth Yacht Club.

From an administrative point of view, the 28th America’s Cup was set although the final decision of the Court of Appeals of the State of New York to uphold the validity of the San Diego defence in Dennis Conner’s multihull wasn’t ratified until April 27th 1990 and thus the date for the next Cup ‘Match’ was shunted from an originally intended 1st May 1991 to the summer of 1992.

The next big decision was the class of boats and with the collusion of various prospective challenges for the 1992 event, a working party of designers met in Southampton, UK organised by Peter de Savary’s Blue Arrow Challenge syndicate to thrash out the next generation of America’s Cup boats. Core to the party were Bruce Farr, Iain Murray, Bruce Nelson, Britton Chance, Ken MacAlpine (measurer), John Marshall and Derek Clark with further inputs from the Japanese team’s Ken Nomoto, Canada I & II’s designer Bruce Kirby and Australia’s Syd Fyscher…plus a notable octogenarian in Olin Stephens.

Early thoughts, actually first presented in 1988, of a super-charged 12-Metre with an elongated waterline of 65.6 feet, an overall length of 85 feet and added sail area, championed initially by Iain Murray was thought to be perhaps a regressive solution and was discarded whilst progress was made at pace to form the new International America’s Cup Class (IACC) that would remain in the competition through to the 2007 Cup.

The result was a measurement class that gave designers scope to develop within a 25-metre length, 24-ton overall weight and a 325 square metre sail surface area, set on a 35-metre carbon mast and held in displacement by a 19 ton bulb. Crew numbers were to be 17 plus an ‘18th man’ which conceivably could be for developing media and sponsor relations whilst thoughts of a ‘Z’ course downwind reaching and running leg of just over 20 miles was developed for better televisuals.

The 1988 Match could well have deterred sponsors and the inevitable billionaire backers, but this simply wasn’t the case for 1992 with no less than ten challengers throwing their hat into the ring although at the final count, only eight made it to the water with the challenges from Russia and Slovenia dropping out. On the defence side, Dennis Conner would be back, albeit with a muted syndicate that struggled to raise corporate backing and who were forced to train only at weekends due to lack of funds – a far cry from Conner’s heyday throughout the 1980’s.

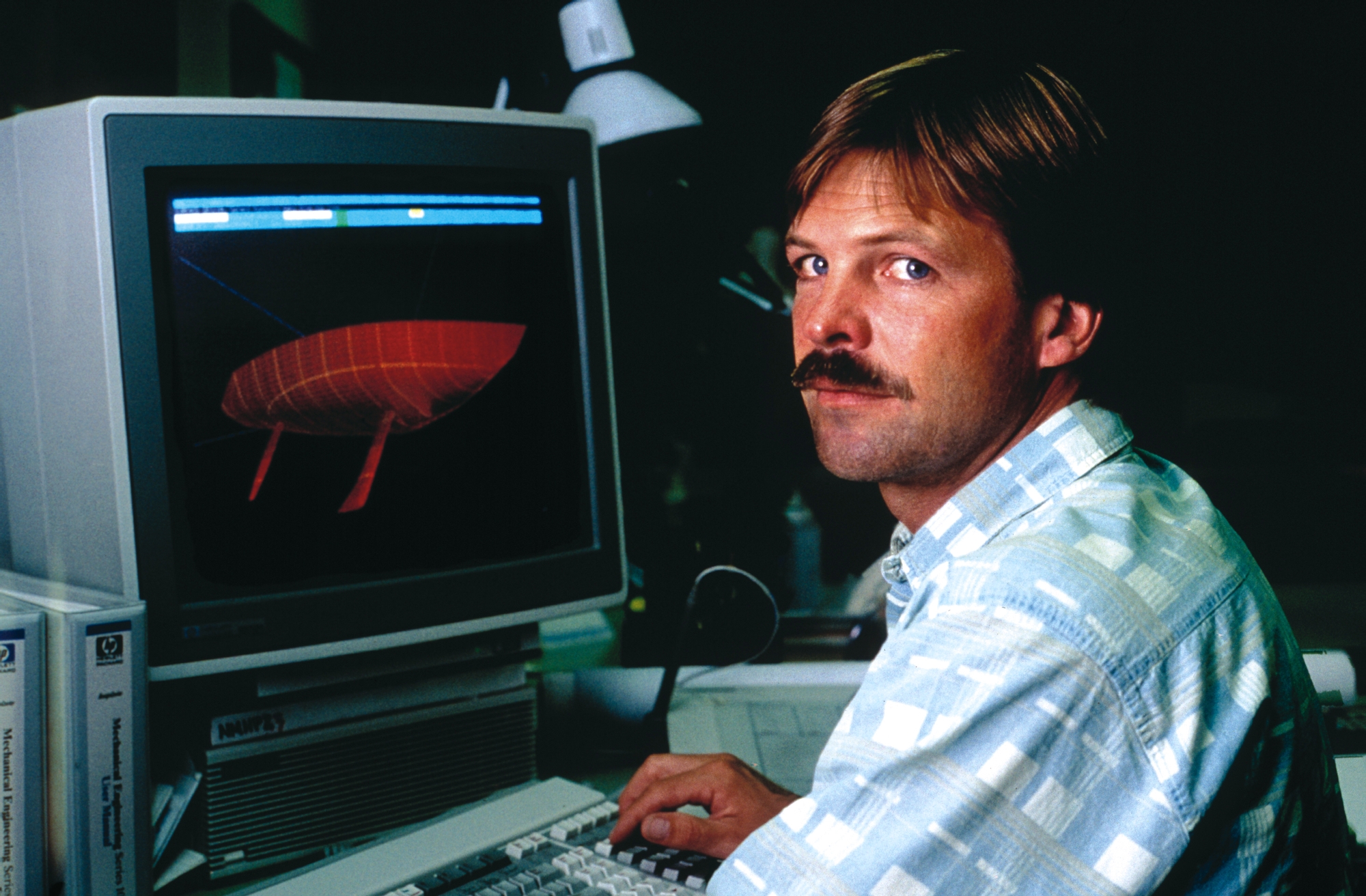

Taking up the American mantel however was the emergence of Bill Koch, an industrialist and intellectual from Kansas who had inherited stock in the family business, Koch Industries, in the early 1980’s and who had netted a vast dollar fortune alongside his brother after a failed attempt to take-over the family company from two further brothers. Koch was a believer in technology having built and campaigned the all-conquering IOR Maxi ‘Matador’ using theoretical data rather than naval design flair and knowledge. A graduate of MIT with a doctorate in Fluid Dynamics, Koch’s design team featured John Reichel, Jim Pugh and Doug Petersen working with data analysts who started out by buying a benchmark boat from the French before going on to build a further four boats after examining some 75 designs and 135 appendage configurations. What emerged was America3 – a boat that from top to bottom pushed the design envelope to the extreme and with Olympic legend Buddy Melges installed as skipper plus Kock sailing onboard with an all-star cast, it was a mighty defence being built for the 27th America’s Cup.

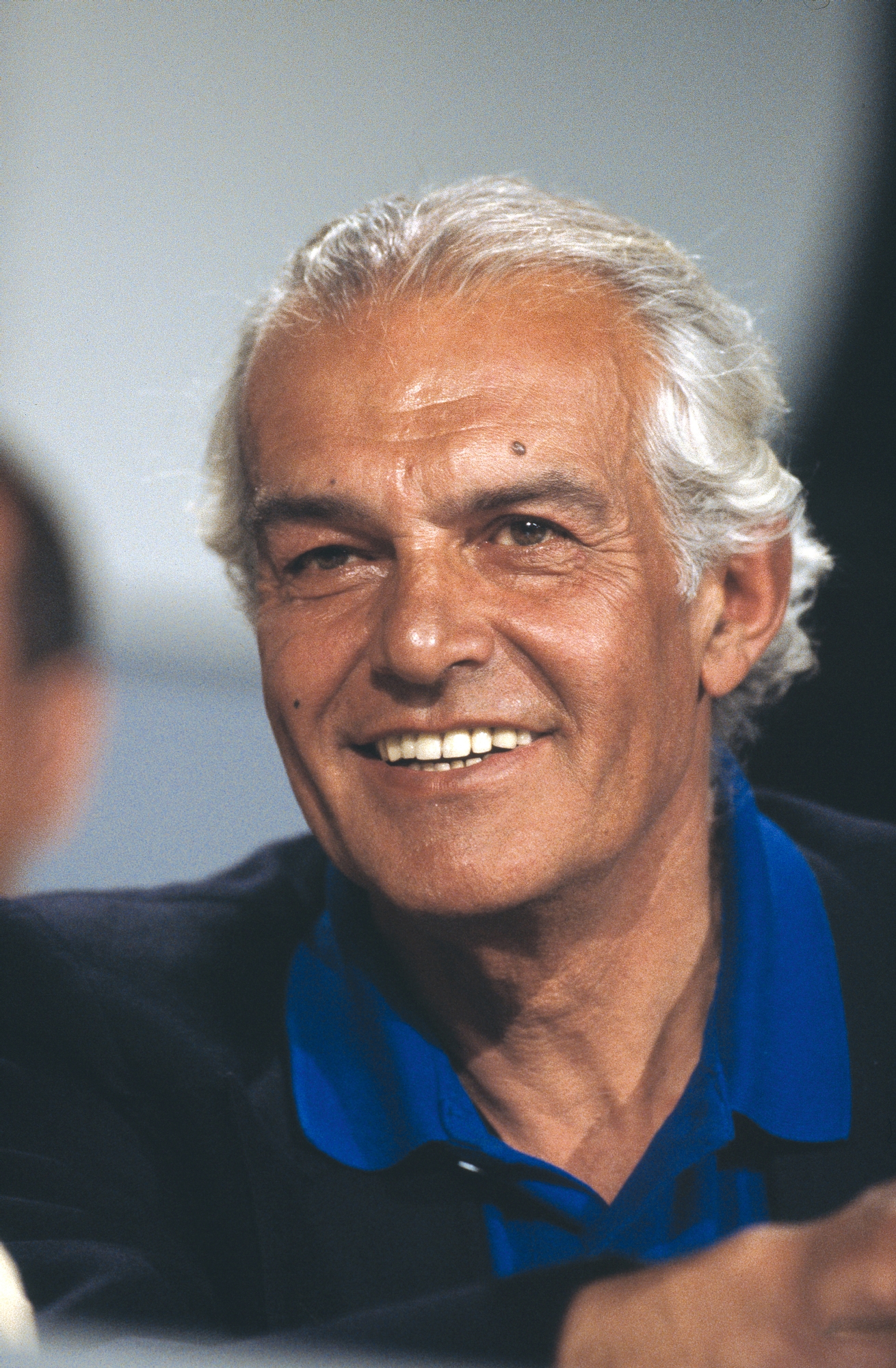

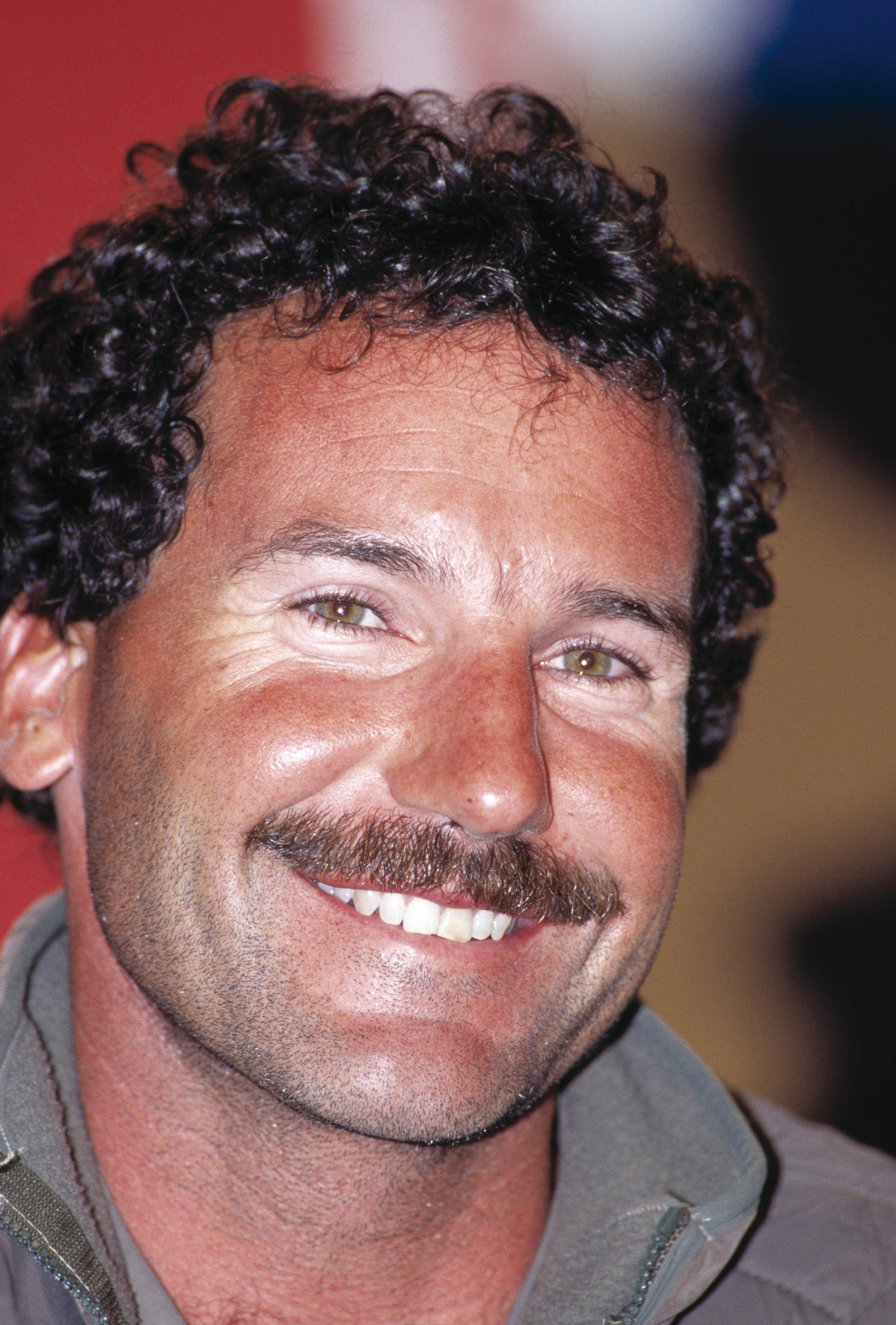

From the challenger side, competition was intense but the emergence of the agri-business and chemicals tycoon Raul Gardini, gave Italy a money-no-object campaign that still to this day resonates as a classy, innovative, memorable and colourful challenge for the America’s Cup. Gardini’s reputed $100 million ‘Compagnia Della Vela’ Challenge heralded from Venice and yielded five boats ranging from lightweight displacement developments of the original Bruce Farr designed baseline for the class and some forays into heavy displacement solutions. All named ‘Il Moro di Venezia’ the campaign launch involved a reputed $3 million carnival in Venice whilst on the sailing side, Gardini recruited first Paul Cayard and as a tuning partner, John Kolius, with the likes of Laurent Esquier joining in a management role from the New Zealand camp.

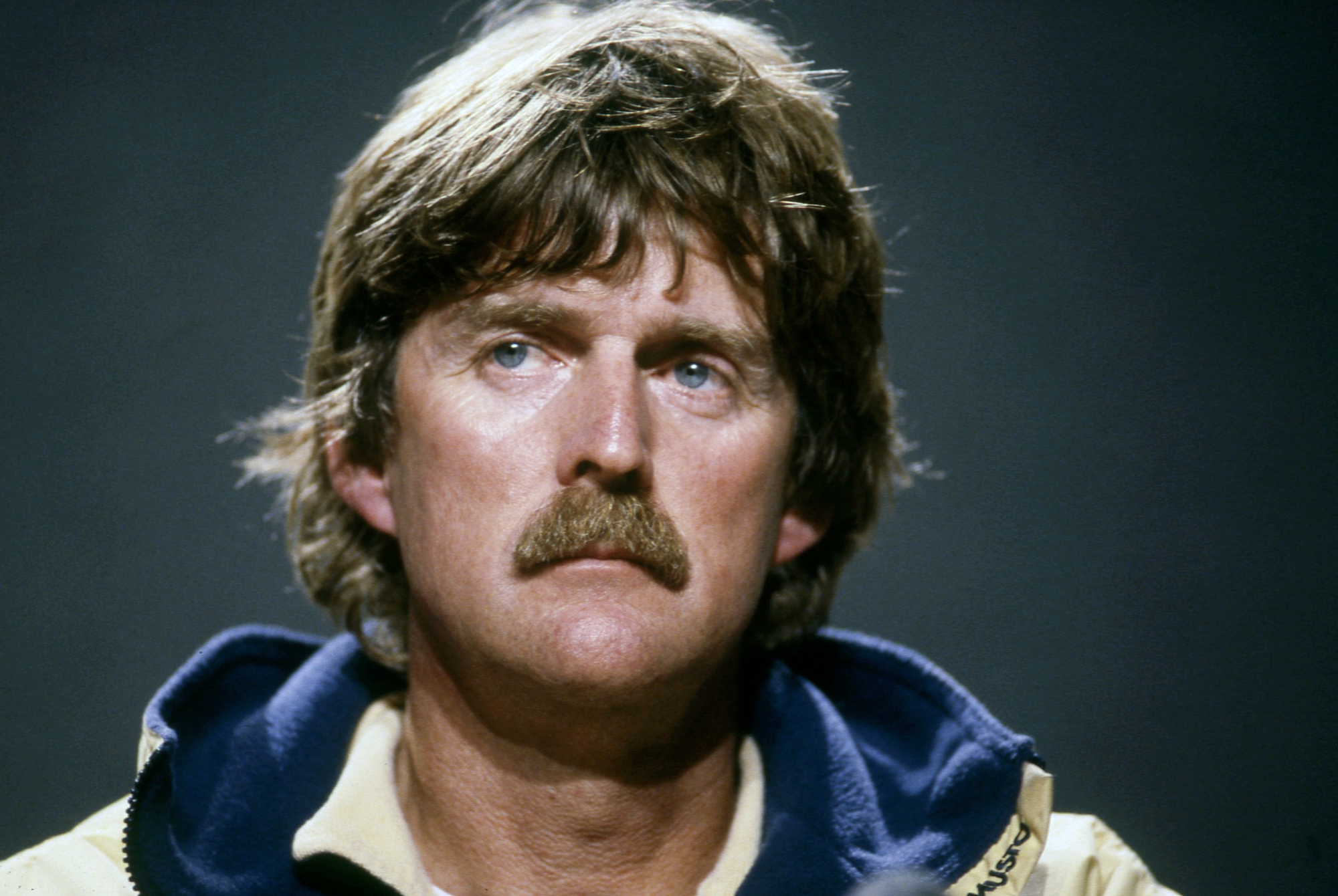

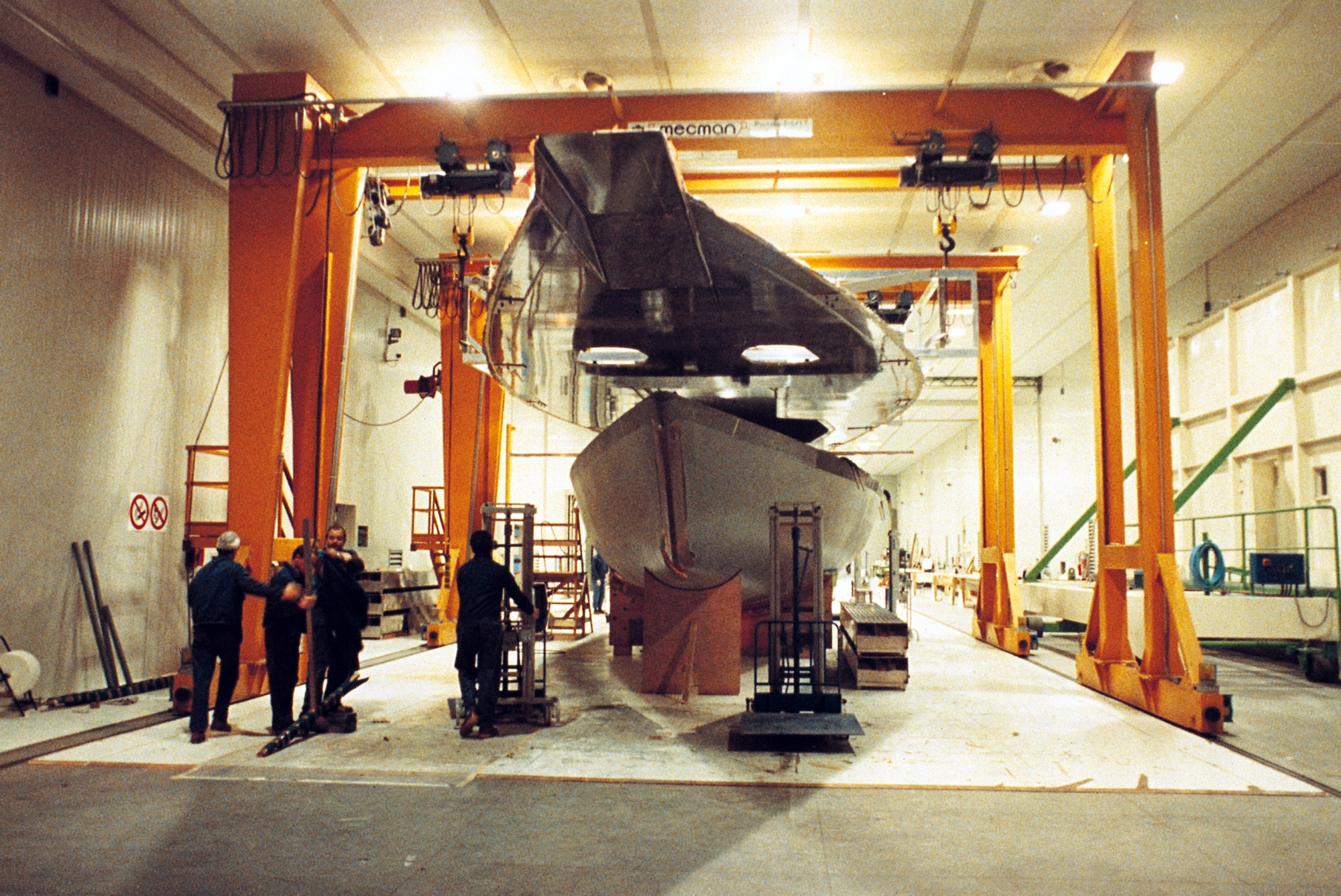

A rather different, but no less effective, approach was taken by the now ‘Sir’ Michael Fay, who had been knighted in the Queen’s Birthday Honours of 1990, again challenging under the Mercury Bay Boating Club burgee. This was to be a four-boat challenge all from the design board of Bruce Farr, one of the key architects of the IACC rule, all built by Marten Marine and Cooksons. The Kiwis took initially a steady approach building two boats identically (Hulls 2 & 3) before allowing Farr to go for a radical, tandem keeled design for hull 4, NZL-20, with a super-light displacement that was a weapon at either end of the wind scale. Where it struggled, and indeed where skipper rod Davis and tactician David Barnes struggled was in the medium airs which was ultimately to be the syndicate’s downfall. Leadership within the camp was also weakened when Esquier left for the Il Moro campaign but bring Peter Blake into the fray late in the campaign with less than a year before the Challenger Selection Series got underway was both foresightful and inspired.

For the other challengers, it was rather lower key, with more reasonable budgets. The Royal Sydney Yacht Squadron’s ‘Challenge Australia’ was one of the first to challenge led by property developer Syd Fyscher whilst a second Australian challenge came from the Darling Harbour Yacht Club with Iain Murray as lead designer. The ‘Spirit of Australia’ challenge went down the tandem keel design route, so impressed was Murray with Tom Blackaller’s 1987 12-Metre ‘USA’ with its moveable appendages.

Sweden came back for 1992 with a challenge under the burgee of the Stenungsbaden Yacht Club that struggled for finance and skirted bankruptcy before a rescue package was agreed and Killian Bushe detailed to build what was to become SWE-19 ‘Tre Kroner.’

Meanwhile, Spain entered the America’s Cup for the very first time with a heavily government backed campaign, Espana ’92, that used the 500th anniversary of the 1492 discovery by Columbus of the New World as a convenient vehicle to support a two-boat challenge from the Monte Real Club de Yates de Bayona. The Japanese came too under the burgee of the Nippon Ocean Racing Club and with superstar helmsman and world match racing champion Chris Dickson leading the sailors. The Japanese crafted a logical three-boat campaign building the first almost identical to Bruce Farr’s baseline design, going radical for the second and conventional for the third whilst sucking up vast computing time and data analysis from leading Japanese companies throughout the design process.

The French were also back in the fray, led by the mercurial Marc Pajot who had become the darling of French sailing after his success with ‘French Kiss’ in 1987. The ‘Ville de Paris’ challenge, under the burgee of the Yacht Club de France, was the first to launch an IACC class yacht and looked set to put up a strong challenge but interim funding issues, resolved by a tie-in with Groupe Legris Industries and the then Paris mayor, Jacques Chirac, saved the day and the team went on to build two further boats – one of which won the first race in the inaugural World Championships of 1991.

An so it was, to San Diego in May 1991 where for the first and only time the new IACC class of yachts lined up against each other before the start of the Louis Vuitton Cup in January 1992. It was close run affair with nearly all syndicates having their day depending on the conditions and how radical their appendage package was but what became apparent were two stand-out performers: Il Moro di Venezia and New Zealand. Dennis Conner had a good showing through the preliminary rounds and qualified for the match-race final but then ducked out citing resources and the toll that the match race discipline had on the boat. Conner’s focus, as ever, was on the prize that mattered.

Il Moro di Venezia won the World Championships of 1991, sending Italian fans wild and with the Bill Koch syndicate, sailing ‘Jayhawk’ that Koch labelled as a “dog”, putting a poor performance on the water with unreliable boatspeed and boat-handling, the Europeans were dreaming of winning and writing a thrilling chapter in history. The big threat was the fast-charging Kiwis and the Nippon Challenge under Chris Dickson. Neither would give any quarter and the stage was set for the Challenger Selection Series to begin with an opening three round robins to decide the top four to then progress the semi-final and final rounds to decide the ultimate challenger.

In the light winds at the end of January 1992, New Zealand’s radical NZL-20 and the Nippon Challenge JPN-26 each finished with six wins out of seven races to top the leaderboard with Nippon Challenge’s only loss coming to New Zealand whilst the Kiwi’s only loss was to Il Moro di Venezia.

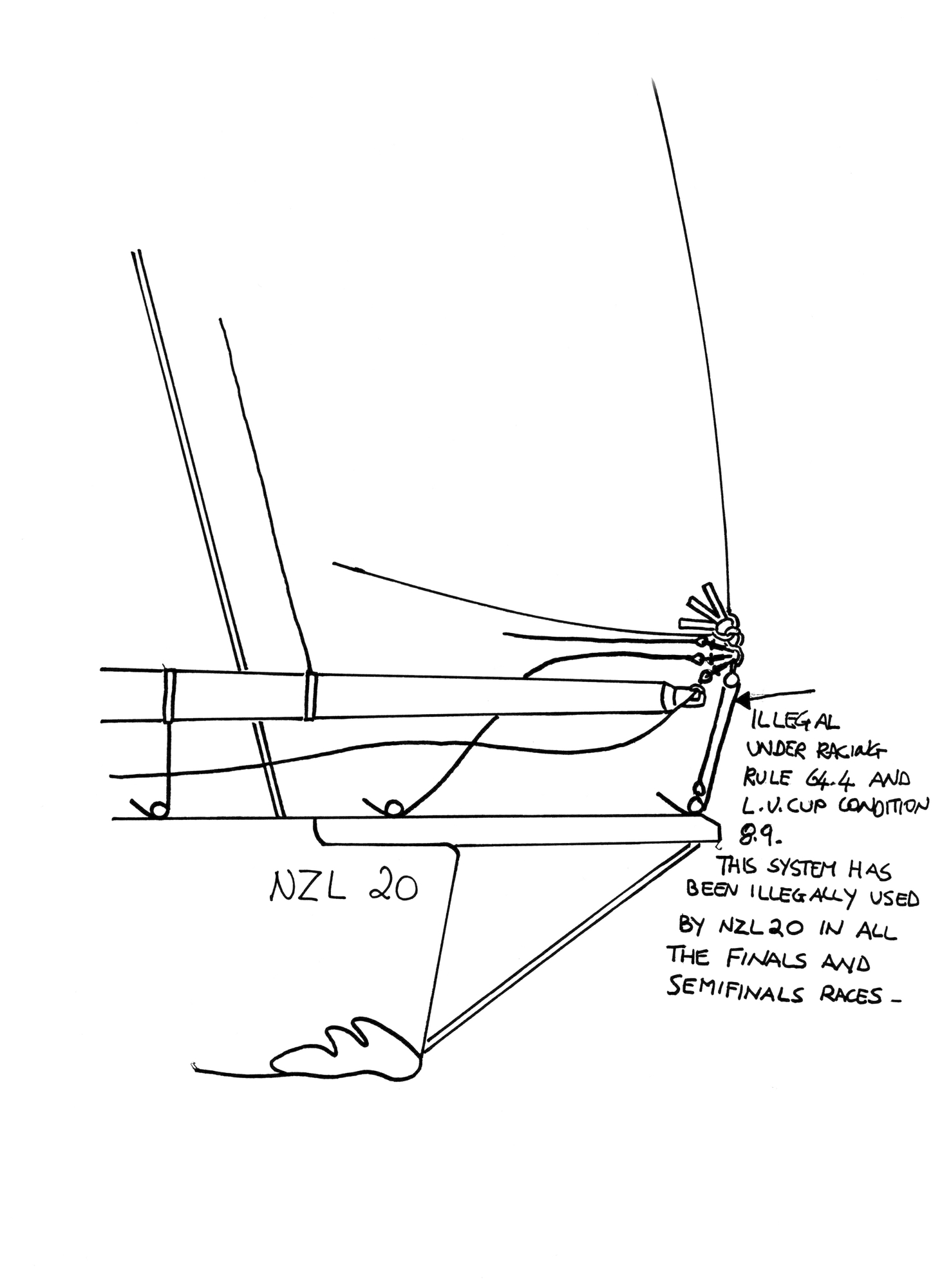

Come the second round-robin between February 16th – 23rd 1992, again the form teams rose to the top with NZL-20 taking a clean sweep of seven victories, il Moro scoring six and Nippon Challenge losing to both the Italians and Kiwis to finish third on five wins. By round robin three between the 7th and 15th March 1992, again the usual order prevailed with NZL-20 topping the standings and Il Moro taking second although the rest of the fleet all had their day as the competition on the water intensified. Off-the-water, however, things were starting to get heated, centred around the way that the Kiwis gybed using their bowsprit as an interim attachment to the gennaker.

This was to be an issue that rumbled on through the rest of the competition, and even today rankles with New Zealand sailors. The International Jury for the Louis Vuitton Cup had ruled, on the very first weekend of racing when Ville de Paris and Il Moro di Venezia protested, that New Zealand’s use of a block and tackle mounted on the bowsprit and affixed to the tack of their gennaker was legal when gybing with no pole connected as it was transferred to the opposite side. The separate entity of the America’s Cup Match Jury had expressed doubts about its legality and immediately with two opposing views, it caused concern that a successful challenging yacht might be ruled illegal, despite sailing all summer, for any America’s Cup Match. It was an issue that the opposing challengers would not drop and arguably was the issue that ultimately holed below the waterline, the New Zealand challenge of 1992.

With the semi-final spots awarded to New Zealand, Il Moro di Venezia, Ville de Paris and Nippon, the stage was set for a battle Royale that rather failed to appear. The big surprise was the demise of Nippon Challenge with Chris Dickson seemingly unable to match the development of both the New Zealand and Italian teams whilst Ville de Paris showed very good downwind speed, something that caught Paul Cayard’s eye, but ultimately couldn’t match the top two teams. New Zealand and Il Moro di Venezia progressed to the Louis Vuitton Cup Final with the French and Japanese eliminated on a whimper despite enjoying arguably the most thrilling race of the semi-finals between themselves on the last day.

Off the water, Il Moro di Venezia approached the French to collaborate on gennaker and spinnaker development but in the opening race of the Finals, after a poor start and trailing around, the Italians lost their biggest margin and ultimately the race when they failed to select a correct gennaker for the first 100° reach and were forced to sail the leg with a genoa. They lost some 33 seconds on that leg, and it was 1-0 to the New Zealanders.

The second race of the Louis Vuitton Cup was a classic with desperate tacking and wonderful gybing duels throughout the race that led to multiple lead changes. Ultimately it came down to a building breeze of 14 knots – conditions that favoured the Italians – and a thrilling final run to the line with the Kiwis protesting Il Moro for not holding proper course (which was rejected) and one second winning margin levelled the series. Rod Davis memorable commented after the race: “It’s giving me a lot of grey hairs, but it will well prepare the eventual winner of the Louis Vuitton Cup.”

Race three saw Paul Cayard make a glamour start before calling a layline into the top mark to perfection to hold a massive 1 minute 42 second lead, however a mis-judgement in not covering diligently on the second beat saw the Kiwis overturn the lead, gain nearly a minute and a half and win the race by 34 seconds. Cayard was stunned and despite his assessment that covering when so far ahead is virtually impossible, allowing the Kiwis to head off right into increasing pressure and a large shift, was a serious error of the Americans’ judgement. 2-1 to the Kiwis.

Race four continued in the same vein with an 8-11 knot breeze that’s aw Rod Davis lead from start to finish in a demonstration of boatspeed that caused much consternation and another registration of displeasure to the Louis Vuitton Cup Committee about how the Kiwis were utilising their spinnaker pole, bowsprit and a strop. Bad blood was spilling between the teams but the scoreline didn’t lie at 4-1 to New Zealand.

Rumblings over the gennaker flying, exploded in race five, a race that the Kiwis utterly dominated to win by 2 minutes and 38 seconds. Upon crossing the line astern, Il Moro flew her protest flag, claiming infringement under the regulations of the Louis Vuitton Cup and the International Yacht Racing Rule 64.4.

The hearing lasted over six hours and the jury found that on legs 4, 5 and 6, New Zealand carried a tight luffed gennaker without a Cunningham patch. At marks 4 and 5, New Zealand gybed with the gennaker. At mark five she bore away to gybe and the after guy was released and the spinnaker pole ceased to have any influence on the setting of the gennaker. The jury noted that for about eight seconds the tack of the gennaker was being controlled by a line at the tack that ran through a block near the end of the bowsprit and thus ruled in Il Moro’s favour and upheld the protest. The jury however didn’t think the sheeting arrangement had a “significant effect” on the outcome but still decided that the most equitable outcome for both parties was the race five be annulled and the scoreline to stand at 3-1 in favour of New Zealand.

The following morning at a hastily arranged press conference, tensions ramped further with Raul Gardini claiming that New Zealand were sailing with an “unsportsmanlike attitude” and Paul Cayard doubling down on his boss’s words and claiming that the jury was skewed consistently in favour of New Zealand throughout the gennaker sheeting debacle. Michael Fay and Bruce Farr offered a robust defence citing earlier rulings and that no intention had been made to circumvent IYRR rule 64.4 but Cayard persisted with his lines and belief that the race should have been awarded to the Italians.

With bad blood in the air, the re-sailed race five was sailed in just 5-9 knots of breeze and saw Il Moro get into the lead early and defend for their lives, eventually winning by 43 seconds after some decent calls from Il Moro’s tactician, Enrico Chieffi, that kept the Italians well in the final and narrow the scoreline to 3-2. Behind the scenes further rumblings about New Zealand’s legitimacy to go forward to the America’s Cup Match should they win the Louis Vuitton Cup continued which brought Dr Stan Reid, Chairman of the Challenger of Record Committee into the fray to clarify their position as Cayard continued to brief his beliefs to the media.

The sixth counting race, and the seventh in total, was held in just 5 knots of breeze and was again another case of Il Moro getting into the lead at one point by over two minutes and defending hard. New Zealand came back on several legs but couldn’t ultimately get close enough to challenge and the Italians levelled the series at 3-3. After two races lost in succession, Peter Blake rang in the changes and appointed Russell Coutts and Brad Butterworth to take charge and add their famed match-racing aggression to the contest replacing Rod David and David Barnes.

Fireworks ensued in the pre-start of race eight with Coutts performing desperately tight circles and Butterworth calling the lead back into the line to perfection. New Zealand led, just, and it was a nervous first beat before Cayard broke through in the final approaches to the top mark and rounded with a seven second lead. It was a lead the Italians stretched down the run with the Ville de Paris spinnaker designs flying and that was the tale of the tape as Il Moro went on to record a 20 second win and the lead in the Louis Vuitton Cup Final.

With his tail up, Cayard was an irresistible force in race nine, at championship point, and guided Il Moro back to the start-line five seconds up after resisting all attempts from Coutts at a foul in the pre-start circling. A favourable first shift out to the right put Il Moro in total control and forced New Zealand to tack to leeward. From there, the Kiwis were shepherded around the course with only minor gains made and by the finish, Il Moro di Venezia won the Louis Vuitton Cup with a 1 minute 33 second resounding victory. The hopes of a nation, in this their very first America’s Cup final, were lit and expectation grew as Italy went wild for the competition and Raul Gardini’s fabulous challenge.

Whilst the Challengers fought it out, the defence of the Cup was an interchangeable three-way affair with Bill Koch bringing two of his five boats, Jayhawk and Defiant, to face-off against Dennis Conner’s poorly funded Stars ‘n’ Stripes in the first round-robin, whilst keeping the true weapon of the 1992 America’s Cup, America3, under wraps until the second round-robin.

The mark of Koch’s campaign was an emphasis on organisational management and throwing the accepted norms of convention out of the window. It was a remarkable campaign that saw the boats get narrower in hull form as development work continued apace whilst all around the boat, innovation abounded, and a crew change from Gary Jobson as tactician to the appointment of Buddy Melges as skipper was a masterstroke with Koch steering often on the team’s second boat and indeed, later in the Match itself.

The big innovation for the America3 programme arguably was in the development of Cuben Fibre sails. Not only was this Carbon Fibre Liquid Crystal Composite lighter, in terms of psychology against particularly the Italians later on, it was the equivalent of Australia II’s winged keel of 1983. Bill Koch had instigated the sail programme, again bucking the accepted wisdom, by approaching a team of researchers at Stanford University and manufactured at a secret facility at Rancho Bernardo up the coast from San Diego. Estimates of weight saving were as high as 40% over conventional Kevlar sails that had dominated at the top end of the sport.

With five boats eventually, ‘Kanza’ being a heavy weather late addition, the America3 syndicate brought a gun to a knife fight in effect, pitted against the one-boat challenge of Dennis Conner and although the wily multiple Cup winner put up a serious challenge, in the end money didn’t just talk, it screamed. The opening round robin saw Defiant top the standings as Conner’s experimental tandem keel failed to perform and ahead of the second round robin, Conner requested to change both the keel and rudder whilst crucially allowing Koch to do the same at any time in the future he desired – and for any boat. America3 was brought into service in the second and third round robins and topped the series whilst Defiant was overcome by Stars ‘n’ Stripes before being switched out for ‘Kanza’ in the semi-finals.

Harold Cudmore was brought in as the match-racing adviser to sharpen up Dave Dellenbaugh and Buddy Melges as Dennis Conner’s crew worked up Stars ‘n’ Stripes to its full potential. Dockside, the chatter was all about Conner coming good just when it mattered like he did so magnificently in 1987 and a win against Kanza and a further one against America3 on the opening two days of the semi-final was pure box-office entertainment from ‘Mr America’s Cup’.

The subsequent days saw Kanza beat America3 and Stars ‘n’ Stripes before Conner thumped America3 in a classic. America3 then went on to beat Kanza before Koch played his keel card and switched out the keel on America3 to an ultra-refined design that saw the boat go on a four-run winning stretch.

What all of this meant was that come the final race between America3 and Kanza, the two in-house boats, the syndicate could have eliminated Stars ‘n’ Stripes if America3 threw the race against Kanza. This sat uneasily with Buddy Melges, skipper of America3 and the syndicate made a wise choice that the final would be best contested with a hard-charging Dennis Conner there to keep everyone honest. Melges won the race against Kanza and then switched boats for the sail-off against Conner – a race that Conner aced and sailed into the Defender trial final with hopes that light airs and his tactical brilliance would undo the might of America3.

The first three races went very much to schedule for America3, winning them all and looking imperious. Conner then snatched one back before Koch’s team eased into a 4-1 lead, three races from winning the automatic defence slot. Conner however wasn’t done and went himself on a three-win streak, showing some incredible match-race tactics and crew-work with tactician Tom Whidden describing race six as their “finest hour.”

With the score all level, interest piqued in the American media, but it was America3 that switched into a completely different gear, shading race nine by 25 seconds, winning race ten by a margin and then thumping Stars ‘n’ Stripes by over five minutes in the eleventh race to win overall by 7-4. Cue wild dockside scenes but not before Dennis Conner added as he crossed the finish line: “Nice job guys, we’ll get ‘em in 1995.” Conner lost with good grace, Bill Koch and Buddy Melges rightly took the plaudits as the focus shifted firmly to the defence of the America’s Cup and the incoming threat of a fired-up Paul Cayard and a money-no-object Il Moro di Venezia campaign.

Going into the Match, the America3 team were confident in their inherent speed and that once in a straight-line Buddy Melges, arguably the greatest natural sailor of all time, could eke the performance gains from the yacht. The great unknown was how Dave Dellenbaugh would react to the white-hot pressure in the pre-starts that Cayard would bring, and this was acknowledged by Harold Cudmore who said; “Dave Dellenbaugh is good, he just hasn’t pre-programmed enough match-racing moves into his memory.” With this in mind, it was no surprise to see the tactics that America3 employed.

Race one of the 28th America’s Cup Match was held in a brisk 12-14 knots on May 9th, 1992, and immediately with rights coming in at the Committee Boat end of the line America3 aimed directly at Il Moro’s mid-ships with what appeared to be heightened aggression from Dellenbaugh. It didn’t last long as Cayard gybed away and into the fast-circling before trailing the Americans out to the spectator boat fleet at the pin end of the line. Once there, Cayard seized control of the left side of the course and tacked on what he assumed was a perfect time-on-distance into the pin end of the line whilst Dellenbaugh headed towards the Committee Boat.

With his transit obscured and a mis-calculation on the tidal flow, Cayard was called over the line and didn’t realise for some 10 seconds that by the time he had re-started, placed Il Moro 30 seconds behind. Dellenbaugh handed over to Melges for the first upwind and after a loose cover, America3 was 31-seconds ahead, a lead that they would stretch by another 11 seconds on the first downwind leg. Into the last gybe, with Bill Koch now steering, an unfortunate incident saw Koch on the floor of the cockpit being treated for a head injury sustained when a loose runner-block struck and Melges took over for the second beat. By the Z-leg reaches, Koch was back on the helm and lost a little time to Il Moro but by the finish it was no mistakes and a 30-second winning delta put the Americans 1-0 up.

Records were set in race two, the following day on 10th May 1992, with the closest ever finish in America’s Cup history at the time. Cayard came into the race fired up that Il Moro was at least a match for America3 and sought to establish dominance from the start.

Again, it was a battle in amongst the spectator fleet with Cayard emerging in the commanding position and whilst the Italians went for a Committee Boat start, Dellenbaugh bailed out to the pin end on a split-tack start with boats even and Il Moro holding the starboard advantage. Only four tacks were completed up the first beat with Melges trying to get the speed out of America3 in a light breeze that slowly built from 6 to 10 knots through the afternoon.

Il Moro rounded the top mark having preserved the right with a 33-second lead and the ensuing gybing duel downwind was so tight to be touching at one point with the spinnaker of America3 grazing the backstay of Il Moro. The on-water umpires flagged it green and Cayard restored a 32-second lead by the bottom mark. A 27-tack beat with the Italians protecting the unfavoured right saw America3 close significantly and by the top mark Il Moro’s lead was down to 20 seconds ahead of the made-for-television Z-course reaching legs.

By the final mark before the last 2.5-mile upwind leg, and with Melges back on the helm, America3 was just 13 seconds adrift and in a classic match race that saw the Americans throw in 39 tacks to the Italian’s 35 tacks to round with a 31 second lead and all was set for a grandstand downwind leg to the finish with America3 clearly holding a downwind speed advantage. Gybe after gybe, the Americans came at the Italians with Cayard protecting the starboard advantage but the Americans closing before the spinnaker got caught on the jumper-struts at the top of the mast on the final gybe on the transit into the finish line. Overlapped, both boats crossed, and a 3-second win was awarded to Il Moro and the Match was all square.

After a lay day on the Monday, Tuesday 12th May 1992 was ultimately dubbed as “Black Tuesday” by Paul Cayard as a first beat nightmare where, having won the start, the shifts just didn’t go Il Moro’s way. With every option available to them, Cayard and tactician Chieffi, called for the right-hand side of the beat with Melges and Dellenbaugh starting down on the pin-end of the line on opposite tacks. As the first shift filtered down the course with a 10-12 knot breeze, America3 lifted into the new breeze and seized a lead that they defended tenaciously. At the top mark the Americans were 47 seconds to the good, a lead that Il Moro eked back into by the leeward mark before the Americans extended on the second beat to lead by just over a minute. The Z-leg was uneventful apart from an ESPN ‘scuba-cam’ getting in the way, something that Cayard protested, but the lead was maintained and by the final beat, Melges protected the right-hand side and won by 1 minute 29 seconds.

Another lay-day was called on Monday the 13th May, 1992 so race four got underway on Tuesday 14th with 12 knots of steady westerly breeze and Cayard dialled into the starting box from the Committee Boat end and immediately headed for the transom of America3 in the ‘push’ position as the Americans again sought refuge, of sorts, in amongst the spectator boat fleet. After a few circles, Cayard came out set up to windward but on the lead back into the line on a port reach with Cayard trailing, Dellenbaugh executed a tight gybe that Cayard couldn’t follow, forcing the Italians to sail down the line towards the Committee Boat. Dellenbaugh claimed the pin end and the left side of the course, whilst Cayard had tacked before the Committee Boat and eventually ended up starting mid-line.

A long drag-race then ensued with Buddy Melges just gaining all the time with additional boatspeed on America3 and as the distance between the two boats narrowed, Il Moro was the first to tack off unable to live in the increasingly dirty air. Naturally, Melges covered with the upper hand secured and by the top mark had a handy 24 second delta. Then came the call of the race with the Americans opting for a gennaker whilst Il Moro set a symmetric spinnaker and by the first leeward mark, the lead was out to 47 seconds.

The second beat saw the wind drop in the middle third to around 7 knots and Il Moro closed in on the stern of America3 to within a couple of boatlengths, but as it came back into double-digits, Melges ‘The Wizard of Zenda’ as he was known, kept calm and sailed into a 27 second lead at the second windward mark. Koch again steered for the Z-leg and by the leeward mark was 34 seconds ahead. A small crew issue with a crewmember getting tangled in a sheet that resulted in two other crew-members going over the side (but retrieved either by holding onto a rope or by the quick thinking of another crewmember) was quickly sorted with minimal loss and the final beat was uneventful with America3 rounding with a 36 second lead. The final run saw the Americans ace the shifts with both boats under symmetric spinnakers and a 1 minute 4 second winning delta took the scoreline to 3-1 and just one win away from defending the 28th America’s Cup Match.

Almost a thousand spectator craft came out to witness the fifth, and what would be the final race, of this thrilling encounter on Thursday 16th May 1992 with news organisations from all over the world heralding the re-birth of the America’s Cup as a sporting contest. Problems arose immediately from the start of the race for America3 with gear failure of the hydraulic ram at deck level causing a crew-member to go up the mast to affix temporary lower running backstays during the pre-start circling where once again, Dave Dellenbaugh ran and hid in the spectator fleet. Cayard was fired up and aggressive onboard Il Moro di Venezia but come the line-up to the start, America3 held the left-hand, pin end of the line whilst Il Moro tacked off onto port and took their chances out right. After an initial couple of minutes of drag racing on opposite tacks, the two tacked in unison and as they came back, Melges tacked right on the Italians’ bow causing them to flip off, but when they came back again, Melges was clear ahead and after a series of some 20 tacks was 18 seconds up at the top mark.

More problems ensued for America3 with a crewmember at the top of the mast this time sorting out batten issues which Il Moro could not capitalise on. The second beat saw America3 stretch her lead through a decent cover out to 38 seconds and then on the first leg of the Z-course, Il Moro blew a gennaker that cost them some 13 seconds before a new one was flying. With the wind increasing Il Moro clawed back some distance on the final beat to be just 24 seconds behind and then threw the kitchen sink at Melges to try and force an error on the final run. Perhaps pushing it too hard, Il Moro lost distance and America3 entered the history books as the winner of the 28th America’s Cup and defended the trophy on behalf of the San Diego Yacht Club.

What Bill Koch achieved with the America3 programme was excellence in every department but a team culture that progressed towards a common goal without individual fanfare or promotion. The only true ‘superstar’ was the late, great Buddy Melges, with whom Koch formed a close bond but the skill of Dave Dellenbaugh and the brilliance of the crew-work from bow to stern cannot be under-estimated. Fusing sailors of the highest quality with scientists, fluid dynamicists, research teams and technical excellence gave America3 that all important ingredient that every America’s Cup winner has – boatspeed – and Koch very much set the bar for the next thirty years.

NEXT UP: 1995 AND A ‘WHITEWASH IN A BLACK BOAT’ AS THE NEXT GENERATION TAKES OVER.